Mexico extradites ‘El Chapo’ son to the U.S. on drug trafficking, other charges : NPR

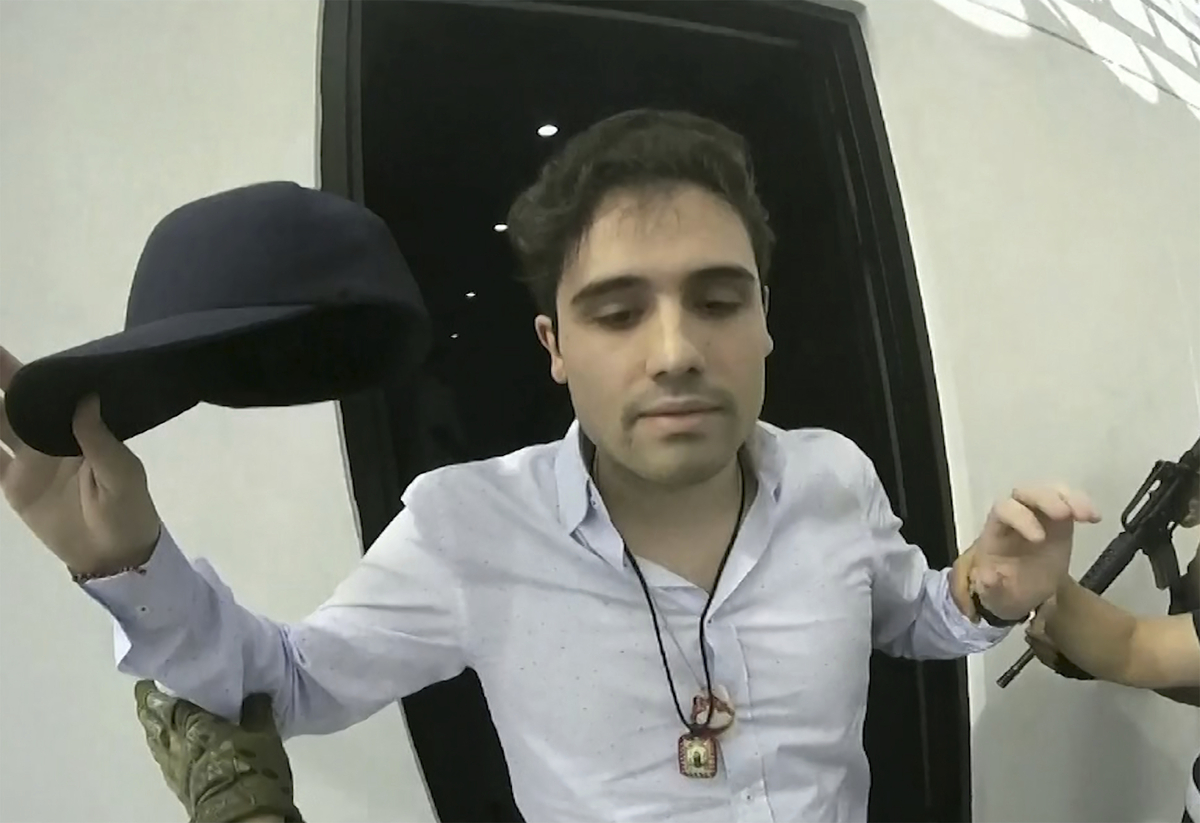

This frame grab from video, provided by the Mexican government, shows Ovidio Guzman Lopez being detained in Culiacan, Mexico, on Oct. 17, 2019.

CEPROPIE via AP File

hide caption

toggle caption

CEPROPIE via AP File

This frame grab from video, provided by the Mexican government, shows Ovidio Guzman Lopez being detained in Culiacan, Mexico, on Oct. 17, 2019.

CEPROPIE via AP File

MEXICO CITY — Mexico extradited Ovidio Guzmán López, a son of former Sinaloa cartel leader Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán, to the United States on Friday to face drug trafficking, money laundering and other charges, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland said in a statement.

“This action is the most recent step in the Justice Department’s effort to attack every aspect of the cartel’s operations,” Garland said.

The Mexican government did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Mexican security forces captured Guzmán López, alias “the Mouse,” in January in Culiacan, capital of Sinaloa state, the cartel’s namesake.

Three years earlier, the government had tried to capture him, but aborted the operation after his cartel allies set off a wave of violence in Culiacan.

January’s arrest set off similar violence that killed 30 people in Culiacan, including 10 military personnel. The army used Black Hawk helicopter gunships against the cartel’s truck-mounted .50-caliber machine guns. Cartel gunmen hit two military aircraft forcing them to land and sent gunmen to the city’s airport where military and civilian aircraft were hit by gunfire.

The capture came just days before U.S. President Joe Biden visited Mexico for bilateral talks followed by the North American Leaders’ Summit.

On Friday, Garland recognized the law enforcement and military members who had given their lives in the U.S. and Mexico. “The Justice Department will continue to hold accountable those responsible for fueling the opioid epidemic that has devastated too many communities across the country.”

Mike Vigil, former head of international operations for the Drug Enforcement Administration, said he believed the Mexican government facilitated the extradition, because for someone of Guzmán López’s high profile it usually takes at least two years to win extradition as attorneys make numerous filings as a delaying tactic.

“This happened quicker than normal,” Vigil said, noting that some conservative members of the U.S. Congress had raised the idea of U.S. military intervention if Mexico did not do more to stop the flow of drugs. Vigil dismissed that idea as “political theater,” but suggested it added pressure on Mexico to act.

Homeland Security Adviser Liz Sherwood-Randall said in statement that the extradition “is testament to the significance of the ongoing cooperation between the American and Mexican governments on countering narcotics and other vital challenges, and we thank our Mexican counterparts for their partnership in working to safeguard our peoples from violent criminals.”

Sherwood-Randall made multiple visits to Mexico this year to meet with President Andrés Manuel López-Obrador, most recently last month.

In April, U.S. prosecutors unsealed sprawling indictments against Guzmán and his brothers, known collectively as the “Chapitos.” They laid out in detail how following their father’s extradition and eventual life sentence in the U.S., the brothers steered the cartel increasingly into synthetic drugs like methamphetamine and the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl.

The indictment unsealed in Manhattan said their goal was to produce huge quantities of fentanyl and sell it at the lowest price. Fentanyl is so cheap to make that the cartel reaps immense profits even wholesaling the drug at 50 cents per pill, prosecutors said. The brothers denied the allegations in a letter.

The Chapitos became known for grotesque violence that appeared to surpass any notions of restraint shown by earlier generations of cartel leaders.

Vigil described Guzmán López as a mid-level leader in the cartel and not even the leader of the brothers.

“It’s a symbolic victory but it’s not going to have any impact whatsoever on the Sinaloa cartel,” he said. “It will continue to function, it will continue to send drugs into the United States, especially being the largest producers of fentanyl.”

Fentanyl has become a top priority in the bilateral security relationship. But López Obrador has described his country as a transit point for precursors coming from China and bound for the U.S., despite assertions by the U.S. government and his own military about fentanyl production in Mexico.

López Obrador blames a deterioration of family values in the U.S. for the high levels of drug addiction in that country.

An estimated 109,680 overdose deaths occurred last year in the United States, according to numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 75,000 of those were linked to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

Inexpensive fentanyl is increasingly cut into other drugs, often without the buyers’ knowledge.

Mexico’s fentanyl seizures typically come when the drug has already been pressed into pills and is headed for the U.S. border.

U.S. prosecutors allege much of the production occurs in and around Culiacan, where the Sinaloa cartel exerts near complete control.