Massive glaciation during the last ice age did not affect nearby Greenland, raising new questions about climate dynamics

OREGON State University

CREDIT: OLIVER DAY, OREGON State University

CORVALLIS, Ore. During the last glacial period, huge ice sheets periodically broke off from an ice sheet that covered large swaths of North America and released the thaw rapidly into the North Atlantic around Greenland, causing devastating effects. sudden global climate change.

These abrupt periods, known as the Heinrich Events, occurred between 16,000 and 60,000 years ago. They have changed the circulation of the world’s oceans, fueled cooling in the North Atlantic, and impacted monsoon rainfall around the world.

But little is known about the effects of events on nearby Greenland, which is thought to be very sensitive to events in the North Atlantic. A new study from Oregon State University researchers, just published in the journal Nature, offers the definitive answer.

“As it turned out, nothing happened in Greenland. The study’s lead author, Kaden Martin, a fourth-year doctoral student in OSU’s College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, said temperatures remained the same. “They had front row seats to see the action but not the performance.”

Instead, the researchers found that these Heinrich events caused rapid warming in Antarctica, at the other end of the globe.

The researchers predict Greenland, which is close to the ice sheet, will experience some kind of cooling. The finding that these Heinrich Events have no discernible impact on temperatures in Greenland is surprising, and could have an impact on scientists’ understanding of the fauna, said study co-author. climate dynamics in the past. Christo Buizertan assistant professor in the College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences.

“If anything, our findings,” said Buizert, a climate change expert who uses ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to reconstruct and understand Earth’s climate history. poses more questions than answers. “This really changes the way we look at these big events in the North Atlantic. It’s puzzling that the remote Antarctic is more responsive than nearby Greenland.”

Scientists drill and preserve ice cores to study past climate history by analyzing dust and tiny air bubbles that have become trapped in the ice over time. Ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica provide important records of Earth’s atmospheric changes over hundreds of thousands of years.

Records from ice cores from those areas serve as a mainstay for scientists’ understanding of past climate events, says Martin, with ice collected from both locations often telling similar story.

The impact of the Heinrich Event on Greenland and Antarctica is still poorly understood, leading Martin and Buizert to try to learn more about what is happening in those parts of the world.

The core used for the latest study was collected in 1992 from the highest point of Greenland, where the ice is about 2 miles thick. Since then, the core has been stored in the National Science Foundation’s Ice Core Facility in Denver.

Advancements in scientific instruments and measurements over the past few decades have provided Martin, Buizert and their colleagues the opportunity to re-examine the core with new methods.

The analysis showed that no change in temperature occurred in Greenland during the Heinrich Event. But it also provides a very clear link between the Heinrich Event and the Antarctic response.

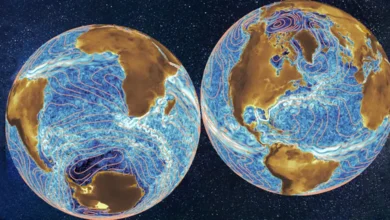

“When these large icebergs hit the Arctic, we now know that Antarctica will react immediately,” Buizert said. “What happens in one part of the world affects the rest of the world. The connection between these hemispheres is likely due to changing global wind patterns.”

This finding challenges current understanding of global climate dynamics during these major events and raises new questions for researchers, Buizert said. The researchers’ next step is to take the new information and run it through climate models to see if the models can reproduce what happened.

“There has to be a story that fits all the evidence, something that connects all the dots,” he said. “Our discovery adds two new dots; it’s not the whole story, and it may not be the main story. Maybe the Pacific plays an important role that we haven’t figured out yet.”

The ultimate goal is to better understand how the climate system is connected and how all its components interact with each other, the researchers say.

“While the Heinrich Event will not happen in the future, abrupt changes in the globally interconnected climate system will happen again,” Martin said. “Understanding the global dynamics of the climate system can help us better predict future impacts and inform how we respond and adapt.”

Other co-authors are Ed Brook, Jon Edwards, Michael Kalk and Ben Riddell-Young of OSU; Ross Beaudette and Jeffrey Severinghaus of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography; and Todd Sowers of Pennsylvania State University.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Global Climate Change Fund and the Gary Comer Education and Science Foundation.

MAGAZINE

Nature

DOI

RESEARCH METHODS

Data/Statistical Analysis

RESEARCH SUBJECTS

Do not apply

ARTICLE TITLE

‘The Dipole Effect and the Heinrich Phase of Climate Change’

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

24-Apr-2023