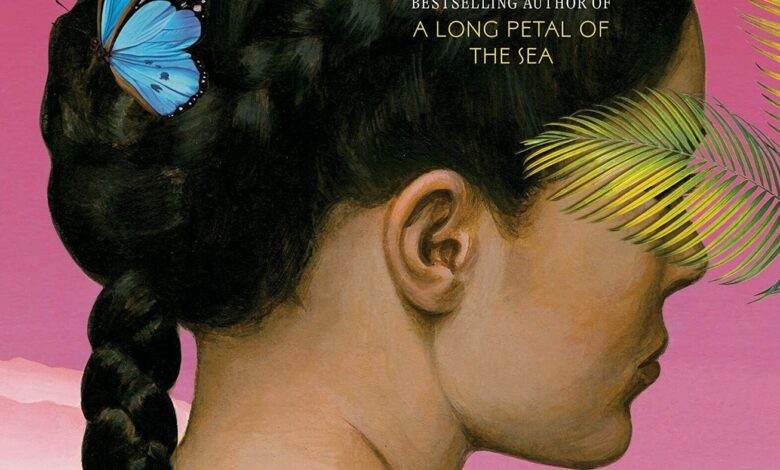

‘The Wind Knows My Name’ by Isabel Allende : NPR

When I learned about Isabel Allende’s new book, The Wind Knows My Name, set in my hometown of Nogales, Arizona, among other places real and mystical, I’ve put it at the top of my reading list. I wanted to find out what she discovered on our border, to see if it would hold as dearly as my memory of the window of my childhood bedroom that opened to the south for the daily breeze. of mixed language, dog barking and grandma’s whistling greetings to neighbours.

In literary career lasted five decades Allende’s narrative follows lyrical romanticism on paths imposed by social and political unrest. This story is an allegory put together by today’s tough news. In her latest novel, Allende breaks down the mainstream narrative of our southern border. She discovers something in Nogales, through El Salvador and Vienna: the possibility of hope and human dignity in the midst of despair.

The Wind Knows My Name is the story of two immigrant children— a boy who escapes from Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1938 and a girl who escapes from military gangs in El Salvador in 2019. The story of Allende blends past and present, tracing their emigration to the United States and the day when immigrant from Vienna – Samuel Adler – and refugee from El Salvador – Anita Diaz – finally met.

We meet Samuel Adler in 1938. He was five years old and was living in Vienna when his father disappeared during the Nazi purge of Kristallnacht. With the help of family allies, Samuel’s mother managed to evacuate him to England. He travels alone, carrying nothing but a change of clothes, a violin, and hopes to be reunited with his parents.

Eighty years later, Anita Diaz and her mother take another train as they leave El Salvador to escape the carnage of military gangs who invade their town and slaughter everyone in it. They arrived in Arizona just as the US government instituted a policy of separating families to prevent refugees. Seven-year-old Anita is currently alone in a camp in Nogales. She escapes the cruel reality and separation from her mother by creating a fantasy world – Azabahar – where traveling without the safety of parents or adults is handled through conversations. A hopeful story between Anita and her imaginary friend, Claudia. Meanwhile, Selena Durán, a social worker in Nogales, hires a legal assistant in hopes of finding Anita’s mother.

Selena’s character seems to be inspired by her mission and real-life work Florence Refugee and Immigrant Rights Project, an organization listed in Allende’s thanks. This group operates in “Ambos Nogales” (Arizona and Sonora) through a partnership with Kino . Border Initiative to provide legal assistance, food, shelter, clothing, and comfort to thousands of refugees and migrants rejected at the border by the U.S. Border Patrol. Selena’s fictional journey comes from a real-life community resource. There’s a lot of real-life Selena in Nogales and along the frontiers. Their kind-hearted neighbor service finds an essential voice in Allende’s story.

Children trapped by geopolitical violence and left to navigate immigration on their own are a core inspiration for The Wind Knows My Name. The story is a love letter to them, and their plight is powerfully evoked through Anita’s conversations with her imaginary friend and frequent visits to the fake world of Azabahar. create. Here again, Allende’s storytelling illuminates real life – that is, coping mechanism children often use to navigate adversity. The Wind Knows My Name responds to the refugee debate with a breathtaking depiction of cruelty. Finding a safe haven is something Allende and her family have also suffered. That life experience is deeply felt in Anita’s imaginary conversations with Claudia:

“I think she’s very close, that’s how we talk to her on the phone. What do you think, Claudia? I don’t cry when we talk to her, even though I’d love to. Well, I did cry a little. little but she didn’t notice.If mom could come pick us up she would, but right now she can’t.She’s crying so that’s why I told her we’re fine where hey. It’s not like being in a hierlera (ice box).”

The shared experience of being away from family, parents and siblings – a trauma that is never left behind – finally unites Anita and Sam. And while Allende’s narrative rhythm is sometimes marked by advocating for social justice as a dialogue, that dialogue is present, relevant, and real. Our civic discourse focuses on a multitude of voices talking about two things – immigration and identity – who belongs to who doesn’t, and how to care for the deprived. In Allende’s version, healing is possible, because empathy is a hopeful, though inconsistent, signal of migration.

A reader interprets the title of Allende’s novel as both a reference and a chorus, revealed at the exact moment when longing is in jeopardy and there is no certainty about finding a home. by Anita and Sam. Their whistle in the dark is a song of hope forever. You can hear it, as I did, in the real-life neighborhoods of Ambos Nogales.

Marcela Davison Aviles is an independent writer and producer living in Northern California.