Svalbard walrus thrives in the face of sea ice decline, mocking predictions of future disaster

Dr. Susan Crockford

The extended visit Of a Immature male walrus arrives in the UK last month (dubbed .) ‘God of thunder’probably from Svalbard, Norway) caused fatigue and emptiness’victims of climate change’ clamor from the peanut gallery, including Bob Ward of the Grantham Institute. However, reality has put all of that to rest.

I wrote about Ward in my book, Sir David Attenborough and the deception of the walrusbecause he has a tenacious habit File a formal complaint when anyone says or write whatever makes sense it just happened to challenge the prevailing narrative that climate change is ruining everything and will drive almost every beloved species to extinction.

And as usual, Ward is wrong again, this time about the Atlantic walrus, which are busy rebuilding their once dwindling populations, leading to near-extinction due to human carnage. for over 350 years. Legal protections against hunting enacted by Norway in 1952 have allowed the species to recover, albeit slowly.

That’s because in some areas (like Svalbard) very few women left to reside on the old pull grounds (NPI 2022), which significantly reduced the rate of recovery until very recently.

Atlantic walrus status

The IUCN Red Book has classified the Atlantic walrus is ‘near endangered’ in 2016: an important step below the ‘vulnerability’ level taking into account the current healthy population. This is despite concerns that the subspecies could face a population decline of >10% within three generations due to loss of sea ice (much less than what Pacific walruses suffer due to the loss of sea ice). food shortages in the 1980s (Fay et al. 1989; Lowry 1985), before anything could be blamed on a lack of sea ice).

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service determined in October 2017 that the Pacific walrus is not harmed by climate change and is not likely to be compromised in the foreseeable future (MacCracken et al. 2017; USFWS 2017). The IUCN Red List (2015) has rated the Pacific walrus as ‘missing data‘ (Lowry 2015). Despite these findings, the IUCN listed walrus species (i.e. both subspecies together), as ‘vulnerable’ (Lowry 2016), apparently based on modeled projections of future decline.

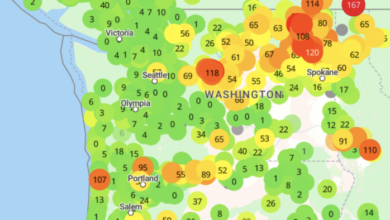

In Svalbard, however, the number of Atlantic walruses has steadily increased as summer sea ice has decreased. The Norwegian website MOSJ has plotted this orbit conveniently, reproduced below:

The numbers on the chart start with two baseline estimates provided in 1980 and 1993 (1980=100 and 1993=741) and end with population numbers from the above unreported surveys. present in 2006, 2012 and 2018 (2006=2629; 2012=3886 ; 2018=5503). That rate was 109% from 2006 to 2018 and 42% from 2012 to 2018: an impressive increase for any which species.

However, the 2016 North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) Report on the Atlantic walrus (updated 2021) shows that the tendency of the animals to stack up in transit causes you can hardly see each individual, even if you are counting them. in a photo. Large numbers of aquatic animals are similarly difficult to count, especially if they are close together and actively dive and swim.

As a result, officials determined that all recent Atlantic walrus numbers may be an underestimation of true population abundance. This means that the 2018 estimate based on an aerial survey is not likely to be underestimated, which means it is highly likely (based on other evidence) that the numbers have continued to rise since then. from that.

sea ice

Arctic sea ice since 1979 has significantly reduced in the summer and very modest in the winter–but from 2007 to 2019, that decline pattern stalled. That is not my opinion but the conclusion of Walt Meier of the US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), who indicated a sideways trend in a published chart. in September 2019. same model continue until 2022:

However, overall sea ice coverage has little effect on the health and survival of Atlantic walruses around Svalbard: what we need to know is what the ice did in the Barents Sea, especially in the past 15 years or so.

Barents sea ice data from 2006 were published by Regehr et al. (2016) but only until 2015. It showed the largest decline of all the Arctic regions: losing 4.11 days per year. It seems likely that this trend could continue into 2022 (Frey et al. 2022).

In other words, the population of Atlantic walruses in Svalbard increased 109% between 2006 and 2018, even as summer sea ice decreased markedly in the Barents Sea.

[In Franz Joseph Land, in the eastern half of the Barents Sea, walrus numbers in 2017 were estimated to be approaching “pre-hunting levels” (9,000-11,000)].

Matt Ridley too, I call it the walrus that thrives in the face of sea ice loss. It mocks model predictions of future disasters based on summer sea ice loss because it is clear that less summer sea ice means more food for walruses and other species (see below). ). On the other hand, winter and early spring ice are only slightly reduced and that’s when the real hippocampus need it to mate and give birth.

Main productivity increase

A report by Frey et al this year (Frey et al. 2022) confirms that primary productivity–generating more food for walrus– continues to increase due to less sea ice cover in summer since 2003, especially in the Barents Sea (Crockford 2021).

In the graph from the report reproduced below, note a marked overall increase in primary productivity in the Barents Sea compared to other regions (left column, 3rd from top): it saw the biggest increase in primary productivity, including a spike in 2017 (year before the last walrus survey).

The increase in food availability for all species (including walruses) means that the carrying capacity of the Barents marine ecosystem has also increased since 2003 – all as a result of summer sea ice. significantly less.

wandering youth

Despite all of the above, we should not forget the individual who started this discussion: a lone man estimated to be 3-5 years old visited the UK in December. In other words, an animal that is less than a decade old is considered reproductive age for males (about 15 years). Adult walruses congregate on sea ice to mate and give birth in winter/early spring (January-April); Immature animals and older animals past reproductive age do not participate in this activity and can roam freely out of the ice (Freitas et al. 2009; NAMMCO 2021).

The wanderer ‘Thor’, as long as he is stuck in shallow coastal areas where he can feed easily (as he seems to have done), is not in any danger from climate change during a stay in the UK, this has the added advantage of being out of range of predatory polar bears.

Presenter

Crockford, SJ 2021. Polar Bear Status Report 2020. Global Warming Policy Foundation Report 48, London. PDF here.

Crockford, SJ 2022. Sir David Attenborough and the deception of the walrus. KDP Amazon.

Fay, FH, Kelly, BP and Season, JL 1989. Managing the exploitation of the Pacific walrus: a trade in delayed response and poor communication. Marine Mammal Science 5:1-16. PDF HERE.

Freitas, C., Kovacs, KM, Ims, RA et al. 2009. Deep in the ice: wintering and habitat selection in the Atlantic walrus. Flow of marine ecology 375:247-261.

Frey, KE, Comiso, JC, Cooper, LW, Garcia-Eidell, C., Grebmeier, JM and Stock, LV 2022. Primary productivity of the Arctic Ocean: the response of marine algae to climate warming and sea ice depletion. Arctic Report Card 2022. DO NOT HAVE.DOI: 10.25923/0je1-te61

Kovacs, KM 2016. Odobenus rosmarus ssp. rose. IUCN Red List of Endangered Species

2016 species: e.T15108A66992323. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T15108A66992323.en

Lowry, L. 1985. “Pacific Walrus – Boom or bust?” Alaska Fish & Game Magazine July/August: 2-5. pdf here.

Lowry, L. 2015. Odobenus rosmarus ssp. divergence. IUCN Red List of Endangered Species 2015: e.T61963499A45228901. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T61963499A45228901.en.

Lowry, L. 2016. Odobenus rosmarus. IUCN Red List of Endangered Species 2016: e.T15106A45228501.

MacCracken, JG, Beatty, WS, Garlich-Miller, JL, Kissling, ML and Snyder, JA 2017. Final species status assessment for the Pacific walrus (divergence Odobenus rosmarus), May 2017 (Version 1.0). United States Fish & Wildlife Service, Anchorage, AK. Pdf here (8.6mb).

NAMMCO. 2021. Atlantic walrus. North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission Report 2016Updated January 2021. Tromso, Norway. https://nammco.no/topics/atlantic-walrus/

NPI (Norwegian Polar Institute). 2022. The walrus population in Svalbard. Environmental Monitoring by Svalbard and Jan Mayen (MOSJ). http://www.mosj.no/en/fauna/marine/walrus-population.html

Regehr, EV, Laidre, KL, Akçakaya, HR, Amstrup, SC, Atwood, TC, Lunn, NJ, et al. 2016. Polar bear conservation status (Ursus maritimus) related to the expected sea ice decline. Biology letter 12:20160556. http://rsbl.royalcietypublishing.org/content/12/12/20160556USFWS 2017.“Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; 12-month results on petitions listing 25 species as endangered or threatened.” [pdf] October 4