Olympic gold never loses its magic

By Steve Bunce

I sat with two Olympic dreamers 10 days before the first bell in Paris.

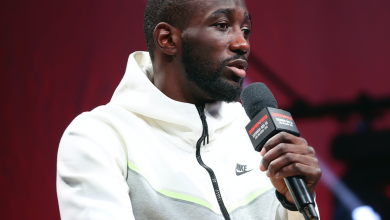

It’s Callum Smith and Tasha Jonas, and the venue is an outdoor bar in Liverpool’s Baltic Triangle.

They had the same dream at the same time, and they dreamed of boxing at the Olympics since they were kids in the Rotunda Gym in the city. It’s the main dream of amateur boxing.

They may have met the 1972 bronze medallist George Turpin, they may know John Hyland from the 1984 Olympics, and they certainly know the Beijing medallist David Price. Liverpool is a boxing village, make no mistake. The day after the Baltic show, I got a message from David Burke, a real medal hopeful from Atlanta in 1996.

All amateur boxers have an Olympic story; they all have memories of watching someone fight in an Olympic competition and they can remember – if they are lucky enough – the first time they saw or held an Olympic medal.

“It was a dream to fight in the Olympics,” Smith recalled. “It was something you wanted and then you started getting closer and closer and then you really wanted it.” Smith’s dream ended, like so many others, in controversy and failure overseas in Olympic qualifying.

In April 2012, the qualifiers took place in Trabzon, Türkiye. Smith was joined by fellow GB contenders Anthony Ogogo, Josh Taylor and Sam Maxwell. It was a gruelling schedule for all of them and, cruelly, an uneven one. In some weight classes, four men made it through and in others, only two.

Smith won three times in four days to reach the semi-finals. Ogogo and Taylor were with him; Taylor lost in the semi-finals but still qualified, and Ogogo made it to the finals. By the end of that summer, Ogogo had won three times, lost in the semi-finals, and won the bronze medal. Ogogo was now the new king of the wrestling ring.

In Smith’s second fight, he easily defeated Montenegro’s Bosco Draskovic, and then overcame Hungary’s Imre Szello to reach the semi-finals and face Azeri Vatan Huseynli. By this time, Ireland’s Joe Ward had been eliminated in the light heavyweight division, the victim of a questionable decision against a local fighter.

In the Baltic Triangle bar, Jonas and Smith looked at each other as the story of the heartbreak of the 2012 Olympics unfolded; they had been to dozens of international tournaments and knew the local boxers who regularly got the nod, the politics that regularly denied British boxers medals. It was the norm, the normal, and their looks summed it all up.

“You see so many bad decisions and you don’t want to be the next one,” Jonas said. “It’s wrong, but you expect it so often.”

In the semifinals in Trabzon, Smith lost to Huseynli 16-14. “I won, no doubt about it,” Smith said. There was nothing he could do about the scoring scandal. In the weeks and days leading up to the first bell in London, everyone on the sidelines in Trabzon told me the same story. Smith had been cheated. It didn’t matter, the dream was over, the Olympics were over. In the light heavyweight division, only two finalists had qualified.

Smith then discovered that Draskovic had been given a special ticket and would be in London in 2012.

“It’s not easy,” Smith said. “It’s not easy to see the guys I beat wearing Olympic jerseys.” Both Draskovic and Huseynli lost their opening matches in London.

A similar thing happened to Jonas in 2016. She had stepped away from the sport after the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow and, apparently, after boxing at the London Olympics. In the summer of 2016, Jonas became a new mother, watched boxing in Rio and saw so many women she had beaten. It was her inspiration, and probably the same for Smith. At the time, it was torture.

“At GB [the gym in Sheffield] “There are pictures of Olympic medalists on the wall,” Jonas says. “You look at them every day and it’s motivation – all those Olympic medalists. I often wonder what it would be like to train and work under those giant pictures if your picture was there. Richie Woodhall does it a few days a week; Lauren Price, Galal Yafai and Karriss Artingstall do it every day. It’s the recognition.

I know fighters from the 70s and 80s, when winning the old ABA title was, in theory, the only way to get to the Olympics, who were in tears because they lost the first step of their imaginary journey to Montreal, Moscow or Los Angeles.

The dream was Montreal, the reality was a majority decision loss in the light heavyweight semi-final of the North East London Championships at 3pm at York Hall.

Hundreds of dreams are dashed around the end of February every Olympic year; the dream is now more complicated as the GB system is firmly established as the only route to potential Olympic glory. It is established, by the way, because it works.

Last week at the Baltic Triangle, as hundreds of fans lined up to take pictures with Smith and Jonas and some of their world championship belts, I saw the surprise in the fans’ eyes as they held the championship belts for the first time.

Seeing Roy Jones wearing about 10 belts all over his body is one thing, but standing between Jonas and Smith and holding an actual belt is another.

Sometime in late 1976, at Cat’s Whiskers in Streatham, Terry Spinks let me hold his Olympic gold medal from Melbourne. I have no photographs, only memories; in 2000, I visited Terry and held it again. It was priceless, a different Olympic dream, but not far from the one Callum Smith had when he got off the plane in Trabzon.