China is a Paralympic star, but its disabled people face huge obstacles: NPR

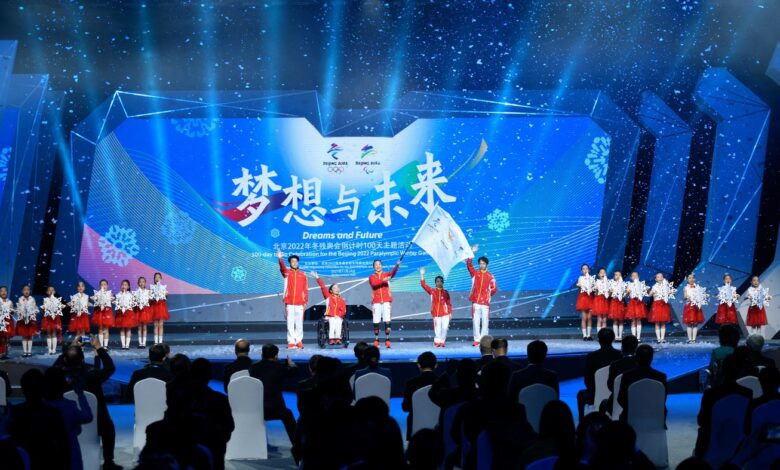

People attend the 100-day countdown event of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics at the National Aquatic Center in Beijing, China, on November 24, 2021.

Wang Zhao / AFP via Getty Images

hide captions

switch captions

Wang Zhao / AFP via Getty Images

People attend the 100-day countdown event of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics at the National Aquatic Center in Beijing, China, on November 24, 2021.

Wang Zhao / AFP via Getty Images

BEIJING – In March, China plans to have 115 highly trained and intense athletes compete in the Chinese Paralympic Team at the Winter Olympics in Beijing.

China has dominated the medal totals at the last five consecutive Paralympic Games and is expected to come back this year. Its method to success? Substantial state funding and a highly competitive track for sporting talents have been identified.

“China has always stood behind athletes with disabilities as an acceptable symbol of modern China that the government cares about,” said Susan Brownell, professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri-St. to the people. Louis, who studies major sporting events. “They have now become more savvy about using the Olympics as a platform to promote their national image.”

However, the system also reflects a paradox: While China supports Paralympic athletes, people with disabilities often face major obstacles in accessing jobs and public spaces in China.

“Sport is one of the few ways that people with disabilities can receive resources from the state,” said Chen Bo, a law professor at Macau University of Science and Technology who specializes in disability outreach.

Ping Yali, China’s first Paralympic gold medalist, says the general difficulties faced by the disabled community have made it harder for them – and given them an advantage over athletes from other countries.

“Paralympic athletes have been forged by hard work; so now that China has given us a chance and cares about us, we have won a lot of medals,” said Ping, who is blind about Legally, say. “Foreign Paralympic athletes did not suffer as we did.”

Ping Yali, China’s first Paralympic gold medalist, carries the flame at the National Stadium during the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Paralympic Games in the Chinese capital on September 6, 2008.

Mark Ralston / AFP via Getty Images

hide captions

switch captions

Mark Ralston / AFP via Getty Images

State funding for the Paralympics

China hosts state-funded and managed Olympic and Paralympic training, setting it apart from other countries, including the United States, where Paralympic and Olympic training is self-funded. Greater funding allows Chinese Paralympic athletes to spend more time training.

However, there is still a significant disparity between Paralympic and Olympic sponsorship. According to public statistics, the sponsorship money for the Paralympics in China last year alone was 20.99 billion yuan ($3.3 billion), half the amount that the General Administration of Sport of China spent on sports events. the country’s Olympic athletes. It wasn’t until Beijing secured the right to host the 2008 Summer Olympics that Paralympic athletes had their own facilities.

Ping recalls that while training in the 1980s, she had to borrow Olympic training facilities during other athletes’ lunch breaks. “Even today, conditions for bodybuilders and disabled athletes are not equal. But they have improved a lot,” she told NPR from her home in western Beijing.

In 1984, Ping flew to Los Angeles to compete in China’s first Paralympic Games. And she won gold – the first Chinese athlete to do so. (For years, China considers her its first Paralympic gold medalist, while touting a non-disabled athlete who won gold in shark shooting more than a month later.) Ping.)

Her victory prompted China to spend more money on Paralympic training.

Ping’s life is symbolic of the gap between Paralympic support and the actual accessibility of people with disabilities. After winning the gold medal, she fell on hard times financially; she gets paid only a fraction of what Olympic athletes are paid. Eventually, she opened a massage parlor run by blind masseuses for a living.

But Ping was lucky. She is constantly promoting accessibility for people with disabilities. She was the first person in China to get a licensed guide dog – a golden retriever named Lucky. In 2008, she and Lucky ran the last Olympic torch relay for the Beijing Summer Olympics.

Snow machines create artificial snow near the ski jumping venue for the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics before the area is closed to visitors, on January 2, in Chongli county, Zhangjiakou, Hebei province, northern China. The area will host skiing and snowboarding events during the Winter Olympics and Paralympic Games.

Kevin Frayer / Getty Images

hide captions

switch captions

Kevin Frayer / Getty Images

Athletes rise through a pathway to pro

Like all Chinese Paralympic athletes, Ping has established a system of hundreds of training centers for the disabled by China’s Disability Sports Bureaufrom which qualified athletes are selected through competition to train at the national level.

The system is structured like a pyramid: At the bottom are dedicated local training centers for people with disabilities, from which the most gifted are selected to train from an early age with the protection of people with disabilities. state aid. It’s best to join the national team.

This sports system used to work in tandem with the historical distinction between people with disabilities and people with disabilities in China’s public education system, a separation that could ironically make determining athletic aptitude. substance becomes easier.

That separation is being broken. In 2014, China started integrated visually impaired and blind students enter public schools. In 2017, a new law allowed all students with disabilities to enter public schools and therefore universities. All of this is a big step forward, says law professor Chen. But he said China still uses the charity model more when it comes to the concept of disability.

“The model of charity is like people with disabilities are the object of pity and the object of charity rather than experiencing real inclusion,” says Chen.

While athletes with disabilities are often seen as a symbol of success, such examples can guide the public conversation about disability in an ineffective way, says Chen: The stigma could be, we encouraged you to work hard, train hard and achieve something, in order to be accepted as an equal member of society.”

Education law is relatively new, so only about 400,000 of China’s approximately 85 million people with disabilities – or, less than half a percent – attend public schools for the non-disabled.

“Objection abounds on many levels – from underserved and overworked general school teachers, from competitive parents of students without disabilities, and from disability governing bodies. at the local level, who are now asked to do more work with only limited increases in funding,” said Di Wu, a researcher who studies disability in China.

Despite these challenges, Wu says China has made strides towards achieving better access and inclusive education. The fact that more and more people with disabilities live and work with people without disabilities can change the perception of the growing community of people with disabilities.

“Accessing requires a change in mindset from seeing disability as a disability that needs to be overcome, to one that actually recognizes people with disabilities,” says Wu, as equal members of the community. society, who have the right and choice to participate in all its aspects. “

Aowen Cao contributed research from Beijing.