Before Serena, Yes Althea

On a sweltering summer day in 1957, a slender young woman from Harlem became the first black player to win the divine Wimbledon tennis tournament in England. After receiving the Venus Rosewater Dish from Queen Elizabeth II, Althea Gibson, 29, attended the Wimbledon Ball that evening, whirling around the dance floor in the Duke of Devonshire’s arms.

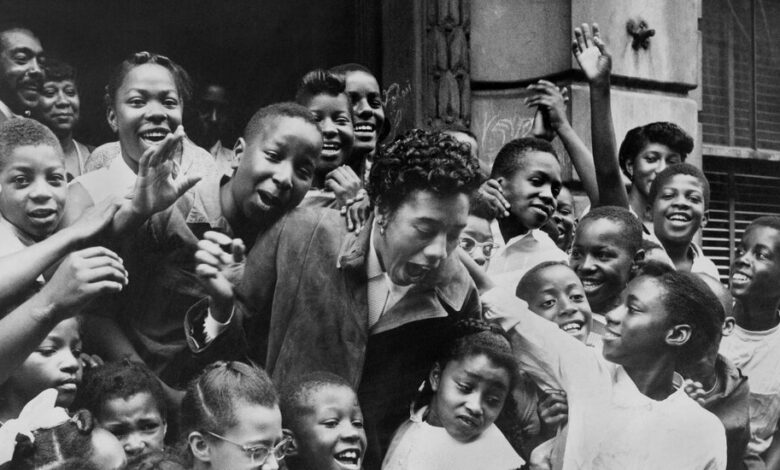

Celebrations continued in Manhattan, where Gibson was kicked off with the first Broadway cheerleading parade to honor a woman of color.

But the next day, the illusion that the new tennis queen had opened a chapter on racial equality was shattered. When Ms. Gibson arrived in suburban Chicago for her next tournament, she was denied bookings at all of the high-end hotels, one of which also refused a request to book a luncheon in her honor.

Back in London, the fairy tale disappeared overnight. Lew Hoad, the Wimbledon men’s singles champion who danced with Ms Gibson at the prom, woke up the next morning to a pile of angry texts, according to Jenny Hoad, his widow. “There were just hundreds of letters from people accusing him of breaking the rules, saying, ‘You have no right to dance with people of color,'” she recalls. “We didn’t even read most of them.”

But Mrs Gibson had no intention of letting the discrimination she fought for most of her life stop her rise and impending reign. Two months later, she became the first black player to win the tournament now known as the US Open, and later that year, she became the first black player to be ranked number one in the world. Her courage and perseverance paved the way for black tennis players to come after her, such as Arthur Ashe, Zina Garrison and the Williams sisters.

Although largely ignored after the 1950s, Mrs. Gibson is finally beginning to come due. On Thursday, which will be her 95th birthday, the 143rd Street neighborhood in Harlem where she took the racket for the first time will be renamed Althea Gibson Way. A life-size statue of a teenage Althea, intended to be erected near the property, is currently being worked on.

Later that day, Ms. Gibson will be honored in a show at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows Corona Park, Queens, home of the US Open, as the tournament begins its 142nd year in a row. . Events, called Nine gods, is a celebration of fraternities and sororities at historically black colleges and universities. (Miss Gibson attended Florida A&M.)

Next year, the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Queens, the former home of the US Open, where Ms Gibson defied racist taunts in her first professional appearance , plans to honor her at its centenary stadium. There’s also a chance that a quarter will look like her in 2025.

According to Michael Giangrande, whose father is the CEO of a sporting goods store, which provides her with free rackets, all the recognition can turn into cold consolation for her. Mr Giangrande, who is expected to speak at the street rename, recalls Ms Gibson lamenting that her titles were the only value she got from tennis, which at the time no cash wallet. “She and my dad used to joke about it, calling the trophies ‘tin cups,’ ‘he said. “Everybody makes money from the sport, except the players.”

To understand how much that has changed, consider Serena Williams. The second black woman to win a Grand Slam singles title, Ms Williams would go on to win 22 more, becoming the most decorated athlete, men or women, to play competitive tennis for the past 20 years. As such, she has also become the highest earner, with a current net worth of $260 million.

When Miss Williams recently announced her can retire after this year’s US Open, she started a professional rotation involving risky investment, among other projects. On the other hand, Mrs. Gibson left tennis only to struggle financially for most of her life, earning a living touring with the Harlem Globetrotters and working as a public representative for a national bakery company, sometimes working into acting and singing, until her death in 2003.

(Both Serena and Venus Williams are admirers of Ms. Gibson. In 1999, Serena, then 17, faxed Ms. Gibson a list of questions related to a school project and the sisters. used a photo of Miss Gibson on the back cover of a black history newsletter they created.)

Ms. Gibson has struggled with poverty for most of her life. As part of the Great Migration, her family left South Carolina in 1929. She arrived in Harlem as a toddler a few months before the stock market crash. To make matters worse, her family is concentrated on 143rd Street, which borders what is known as a “lung mass,” as the TB death rate for residents there is twice as high as in other areas. other Manhattan neighborhoods, according to the 1939 New York City Guide.

Claude Brown, Gibson’s first cousin and author of the best-selling autobiographical novel Manchild in the Promised Land“ also grew up in Harlem, surrounded by alcoholism and street violence, which he wrote about in the book. By the age of 9, the main character of “Manchild” was “hit by a bus, thrown into the Harlem River (intentionally), hit a car, beaten with a chain” and set the house on fire.

Miss Gibson is no stranger to such difficulties. A towering girl from her earliest days, she spent most of her time shopping on the streets and fighting street gangs. Her father, Daniel Gibson, a garage worker, hopes that his daughter will become a competitive boxer and often takes her to the rooftop of their building to practice. But when his lessons sometimes turned into beatings, she joined the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, which, as she wrote in her autobiography, gave her shelter.

Another haven for Althea is the Apollo Theatre. She enjoys singing and playing the saxophone, and often plays hooky to attend performances there. In 1943, she won second prize in the Apollo stage singing competition. But instead of a week of singing there, which she had been promised, Althea was awarded $10. “I cannot complain,” Ms. Gibson wrote in her autobiography. “That $10 bought a mess of fried chicken, collard greens, and root beer.”

For Althea, competition is a way of life. She just participates in any sport that involves balls. Basketball is one of her favorite sports and she is the fastest member of the team Mysterious Girls Athletic Club, the famous Harlem basketball team. Once, she and her teammates ran into champion boxer Sugar Ray Robinson in a bowling alley, and she challenged him immediately, declaring, “I can beat you at bowling in no time. now!”

In 1937, when the Police Athletic League organized a raid on 143rd Street to provide a safe play space for children, 10-year-old Althea discovered paddle tennis. Two years later, she became the city’s tennis champion. Not long after, Buddy Walker, a Harlem band member and tournament supervisor, bought Gibson a pair of used tennis rackets.

According to her account, Ms Gibson did not at first feel that tennis would be a natural fit for her. “I remember thinking to myself it was like a matador walking into the bull ring, well dressed, bowing in all directions,” she wrote in her autobiography. “And all the time, there’s nothing on my mind except to stick that sword in the bull’s gut and kill it like hell.”

Mr. Walker also introduced her to Cosmopolitan Club, the local Black tennis club where Harlem’s most prosperous residents play. Before long, she was beating everyone she played with. Club members put up a collection and sent her to tournaments around the country due to American Tennis Associationa tournament for Black players.

By 1947, at the age of 20, Ms. Gibson had won her first ATA title and went on to win 10 national championships, a record that still stands. Bob Davisone of Ms Gibson’s spanking partners, recalls that she was so aggressive on court that just gathering with her could be intimidating.

“Althea was a tough girl,” recalls Mr. Davis, a four-time ATA champion herself and the 2006 United States Tennis Association (USTA) mixed doubles champion. Totally happy to knock you down with the ball. She hit me. Every time we play, she tries and hits me.”

Ms. Gibson smashed and campaigned her way to the top ranks of tennis, breaking the color barrier to the sport in 1950 when she became the first black woman to compete. compete in the US Open. By the end of the decade, she had amassed a total of 11 Grand Slam titles, including multiple titles at Wimbledon, the US Open and the French Open, where in 1956 she won titles in both events. single and double. But for Miss Gibson, even that wasn’t enough. Soon after retiring from tennis, she jumped into another sport, and in 1964 she became the first black woman to join the Women’s Professional Golf Association.

“Everything Althea has to do is three times harder than it is for a non-black person to do everything,” said Katrina Adams, a former professional tennis player and first black person to serve as USTA president. . was transcendent. “

Sally H. Jacobs is the author of the biography “Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson,” which will be published next year.