Why is the aurora forecast not as good as the weather forecast?

On Friday afternoon, the NOAA Space Weather Center predicted a major aurora in the Northwest, and it happened. A tremendous event to see. At the same time, the Center had predicted an important event to take place on Saturday night but it never happened.

Aurora forecasts a day or two in advance often fail, while weather forecasts are generally near-perfect for the next few days.

Why is there a difference between weather forecasts and aurora borealis?

To understand the problem of aurora forecasting, you must understand why auroras occur.

Auroras often begin with a disturbance on the solar surface, such as a solar flare or coronal mass ejection (CME)—see below. Note that the corona is the outermost layer of the sun.

Courtesy of NASA

These disturbances push large numbers of charged particles moving at great speeds (like a million miles per hour!) away from the sun. Such ejections of charged particles can also change the magnetic field around the sun. I should note that even if there were no turbulence on the sun, this is still the amount of background particles leaving the sun, called wind.

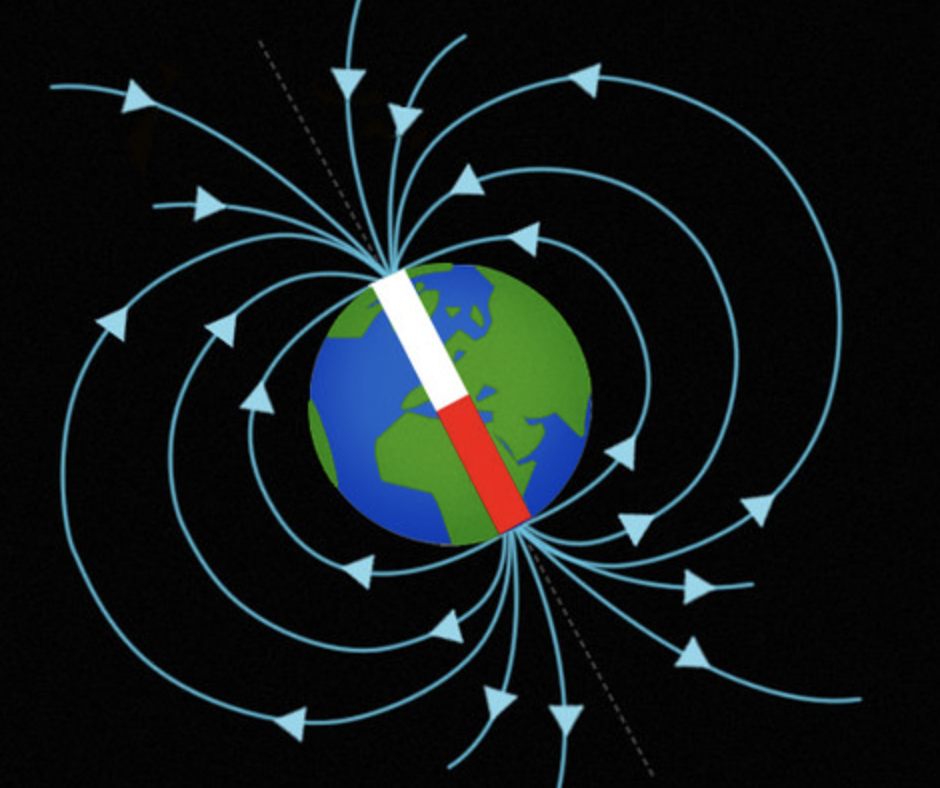

The Sun has a magnetic field around it and so does the Earth (see below, from Zappys). Note how the magnetic field lines (light blue) approach and leave the polar regions.

Now comes the important part. When particles from the sun (solar wind) come close to the earth, they interact with the earth’s magnetic field, so solar particles can enter the earth’s atmosphere near the poles…or actually actually a circle around the poles centered on the earth’s magnetic poles (see below).

These solar particles can interact with various atoms/molecules in the atmosphere (like oxygen and nitrogen), causing them to glow (like neon tubes). This is what causes the aurora colors.

During a solar storm, the number of particles leaving the sun increases, and they can reach Earth a day or two later. This increases the aurora. It also disturbs the earth’s magnetic field.

The problem of predicting auroras

Astronomers have little skill in predicting disturbances on the solar surface. Yes, we know that flares, sunspots, and CMEs occur more frequently during the peak of the 11-year sunspot cycle, but the skill of predicting individual events—these Friday’s auroral enhancement event– was minimal.

But it’s worse than that. The speed and direction of particle ejection vary depending on the event, and it is difficult to observe such parameters from Earth.

It’s like predicting where the ball will go without knowing its exact speed and direction.

But there is some useful information in a very short period of time. NASA and other organizations have spacecraft traveling between Earth and the sun at what is called the L1 point, about a million miles from the sun (see below).

Such spacecraft could sense solar particles approaching Earth and provide reliable observations of changes 30 minutes to an hour before they reach Earth, making predictions Aurora has high precision. On Saturday afternoon, an L1 satellite created warming before solar particles approached and new aurorae appeared. When I saw that data, I called my friends to throw an aurora party.

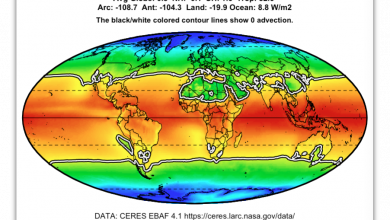

Now, the NOAA Space Weather Center has recorded another CME on the solar surface and predicts the possibility of a small aurora tomorrow night (see below). So I’ll look at the L1 satellite data, just in case the forecast turns out to be wrong.