Truth or consequences: global warming consensus thinking and the decline of public debate

by Geoffrey Weiss and Claude Roessiger

The so-called debate about the causes and effects of anthropogenic global warming (AGW) is a notable irony. Rather than a forum for free disputation, AGW has in recent years become the site of a consensus equating majority opinion with truth—leaving little, if any, room for debate. After all, doesn’t everyone but a misguided few agree that we are in the grip of an unparalleled, man- made climatic catastrophe?

Challenging this consensus and its advocates often leads not to reasoned argument and coolheaded policy making but to sometimes overheated recrimination and silencing of those with alternative interpretations. This we discovered firsthand when, as close observers of AGW controversies since 2015, we convened a conference about climate change and public policy.

Unanticipated events preceding the conference were an unsettling enough demonstration of the rule of consensus in contemporary life. Worse still, subsequent inquiry revealed that the AGW conference was just the tip of a bigger and—according to consensus—fast-melting iceberg. Beyond our conference and the controversies surrounding AGW, consensus thinking adversely impacts diverse other current issues, individual awareness of them, public discourse, policy making, the practice of science, and collective understanding of the nature of truth.

Conference planning and the sway of consensus

Our own diverse perspectives on AGW—those of an entrepreneur and a physician—led us to believe that the proposed conference would attract a wide range of participants. We envisioned a gathering of experts from the academy, government, industry, and other interests who would debate the impact of AGW upon public policy. Our goal was to convene a gathering of approximately 30 speakers and 500 attendees at the conference facilities of a local public university. The initial meeting of our planning board and three university faculty members was cordial and evoked considerable enthusiasm for the conference—until we presented our list of speakers. The lineup included an even balance of individuals who were either proponents or skeptics of AGW. And, with that, we collided with the first of the consensus advocates who would take issue with our approach.

“This program of speakers is unacceptable to us,” the faculty leader stated. “It has several climate change deniers. You know, of course, 97 percent of scientists agree that global warming is real and that it is a consequence of human activity.”

Lacking the support of university faculty, we engaged the conference facilities of a nearby hotel and proceeded with fund-raising. In August 2018—just two months before the scheduled event—AGW activists alerted members of the host city council to the controversial panel of speakers. As a result, the city leadership rescinded their endorsement and financial support of the conference.

“It was a concern about why alternative views [of climate change] would be spoken of that are not held by 99 percent of climate scientists,” claimed one councilor to a local newspaper. “[It is] reprising the whole debate about climate science.” He didn’t want the city, which had championed several environmental issues, “giving speakers like that a forum.”

Despite this setback, the conference opened as planned in October 2018. A capacity audience attended, and the discussions were generally well received, with only a small contingent of university representatives betraying their scorn. At its conclusion, the conference provided several themes around which the speakers and attendees could agree. Reviews were mixed—some finding no common ground with many of the speakers’ views, others praising the planners’ efforts.

Conference aftermath: three crucial questions

Our purpose in designing the conference was to provide an educational event and discussion forum for a regional audience of policy makers, business leaders, and professional stakeholders interested in the policy implications of AGW. Several of the speakers were skeptical of the pace of global warming or of global policy favoring the rapid development of renewable energy resources in response to AGW—but not one denied AGW.

Little did we realize how polarizing the conference would be. In particular, we were struck by the vehemence with which the local university scientists withdrew their cooperation upon learning the composition of the speaker panel. It seemed to us that they had no interest in engaging with a discussion regarding AGW and its effects—topics that, to them, closed all argument because the solutions seemed certain. The loss of our municipal sponsorship and the accompanying publicity in the local press further alerted us that forces were actively at work to undermine our project.

Our efforts to understand what led others to disengage from us and to decline our invitation to debate raised three questions: 1) Why did academic scientists avoid this opportunity to consider the AGW consensus with a few of its challengers? 2) How do scientists, the media, policy makers, and the laity acquire reliable technical information upon which to base decision making? 3) What is the difference between deniers of science and skeptics of science? We asked these questions because the cultural mood at the time of our conference seemed so emotionally charged that it prompted some to boycott discussion.

Science, faith, and consensus

In addressing why academic scientists spurned the conference, we might begin by considering how scientific truth differs from faith—in this case, faith in the AGW consensus. We sought the insights of a scholar of philosophy to guide our thesis. Generally speaking, faith leads from theory to a search for evidence, whereas scientific truth derives from empirical evidence that defines a theory. The distinction suggests philosophy’s query: What is truth? Rather than conflating truth and majority opinion, science pursues a measured truth that, at least for a time, can meet the rigorous test of the scientific method. If we seek any form of absolute truth, we shall find it only in faith—and not in empirical science. As the philosopher Karl Popper suggested in The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959), a theory that cannot be falsified is faith, not science.

Consensus thinking should not be confused with consensus science. It is a historical truism that all science tends to consensus until it does not, at which point a new consensus forms around a new insight. Alfred Wegener, often considered the progenitor of continental drift theory, was derided and ostracized when he first proposed his thesis. Over time, empirical evidence disproved older notions, and today we take Wegener’s insight for the consensus belief. And tomorrow? We don’t know. New research may lead to yet another understanding. To deny that research would be to declare ourselves for a faith. It seems that a body of academics today have become brokers for a faith, shutting down—or shouting down—the continuation of scientific inquiry.

As human knowledge expands exponentially, we must admit the possibility of many corrections and new hypotheses that may lead us to new understandings. Nothing will serve us better than unbiased science guided by observation, the established scientific method. Science of this caliber not only demonstrates the transience of consensus but also, when informed by philosophy, helps elucidate the nature of truth.

Science, truth, and the role of philosophy

Since ancient times, scientific findings divergent from accepted thought have been regarded with skepticism, denial, and even contempt. Skepticism of new scientific ideas is inherent in the scientific method and ensures that fresh concepts are rigorously examined and rendered free of error before their general preferment. Denial and contempt, the scientific community agrees, have no place in experimental inquiry. Yet past and present examples are easily found.

In the early 1960s, Judah Folkman, MD—more recently a pediatric surgeon at Boston Children’s Hospital—conducted research indicating that cancers require the formation of new blood vessels to sustain their growth. This process, he suggested, had potential for developing cancer therapeutics. The ASCO Post, December 10, 2020, recalled the disbelief by granting agencies and mockery from competing researchers that Folkman faced; conventional scientific wisdom judged his ideas to be too illusory for serious attention. Then, in 1992, Napoleone Ferrara, a scientist at Genentech, Inc., identified a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a potent stimulus to new blood vessel formation. Folkman’s hypothesis was acquitted. Cancer therapies targeted against VEGF were quickly synthesized and shown to be effective against certain malignancies.

Folkman’s experience suggests that consensus, in science and elsewhere, too readily excludes what the French call recul. Best understood as detachment, the term embodies the notion that, in the presence of uncertainty, a space be reserved for perspective. This allows for the possibility that different forms of truth may become entangled to advantage. In the 18th century, what we today take for a scientist was known as a philosopher. Such was Benjamin Franklin, one of the foremost scientists of his time. Those that think science is dispassionate sense while believing philosophy to be impassioned nonsense would do well to consider Franklin: Was there a man more pragmatic? When Franklin and Voltaire met in France, they were hailed as the Enlightenment’s union of empirical knowledge and wisdom. We miss this union now, believing science complete of itself. This suggests the first of four corrective truisms concerning the alliance of science and philosophy: knowledge without wisdom is a tool within an otherwise empty box.

This leads toward a second truism. Contemporary science is widely held to be the bearer of things known. This cannot be, however, because empirical science, ever subject to question, can only represent a moment in time. In science the known and the unknown are the obverse and reverse of one coin, one without the other being at best half an explanation. Thus, the second truism: in all things, there exist the known and the unknown.

A 1927 essay, “Possible Worlds,” by the English biologist J. B. S. Haldane, characterizes the universe as “not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” Science has had to face the challenge of the unknown, understanding that only by the union of philosophy and science can knowledge be advanced. In Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray (2018) the German theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder observes that “science has reached a limit at which it must be rescued by philosophy.”

Earlier, in writing Dieu et la science (1991), Jean Guitton, the renowned 20th-century French philosopher, concluded that he could detect no opposition between God and science but, rather, complementarity. The same might be said of philosophy and science. Although it can offer critical thinking, philosophy is not a critique of science, but an equal, complementary discipline. Philosophy advances its own claims, based on a long-tested process as rigorous as the scientific method. The representation in some circles that science offers absolute truth is thus in error and brings us to our third truism: science without philosophy is half a horse.

The ancient Greeks understood this. The word γνώση, transcribed as gnosi, encompasses what in English requires more than a word: that is, knowledge, cognition, awareness, learning, and sense. Beyond these lies what is not known. The quantum physicist tells us, with a straight face, that the laptop upon which we write our words is, and is not, the paradox of Schrödinger’s cat—in other words, the threshold beyond which the unknown lies. Here we arrive at our fourth truism: the unknown is the dark matter of all things, the greater part of our universe.

Hossenfelder is critical of theory in search of evidence: empirical evidence would do better in pursuit of theory. In her view, lacking empirical evidence of the unknown, a coterie of

“Truth or Consequences” | Page 5 of 12

physicists has taken up a game of mathematical pyrotechnics, formulating equations to support increasingly arcane hypotheses about what they cannot for now explain. Then prejudice—today called confirmation bias—intrudes, whereby such fragments as may be supposed evidence are taken for whole stone. These researchers might productively emulate philosophers, who follow procedures as defined and tempered as those of empirical science. The police of every land have a rule: a murder without a body is not a murder. In science—even, or perhaps especially, in the realm of the unknown—a theory without evidence is not a theory.

Our four truisms not only suggest a deep interconnection between science and philosophy but also help nullify the false premise that there is no truth. Based on our inquiry, we can affirm that truth exists and may be fairly assayed by diligent processes long established in both science and philosophy. It is by turning our backs on these processes that we lose ourselves.

The importance of understanding truth in contemporary public life

In our interaction with civic authorities and the media we were bewildered about how and why they had taken a position against our conference. How had they come to the judgment that our forum offered a message potentially too damaging to endorse? Drawn from legitimate academic, religious, scientific, and policy centers, our speakers were not invited to promote a single way of thinking. Who would want to attend a meeting in which everyone agreed upon a topic?

Hence, the second question that resulted from our conference: How do scientists, the media, policy makers, the laity—any of us who have a stake in learning and understanding the truth—acquire reliable information to support decision making?

Debate about the status of truth has endured since the origins of philosophical thought. Some argue that truth is entirely subjective, residing in the realm of the individual observer. Others insist that truth must be objective, that it belongs not to human beings but to the laws of nature. Most philosophers have attempted to navigate between these two poles, noting that the first leads to skepticism while the latter is simply impossible insofar as the human observer always adds an interpretative element to even the most impartial of truths. While craving a certainty that exceeds the boundaries of human thought, the human mind is in fact prisoner of its own subjectivity. We can never think beyond our own minds, perceptions, biases, and presuppositions. This suggests that the concept of truth is less stable and less independent than we might want to admit.

Even so, we are not forced to conclude that truth is only a matter of subjective understanding. To take this position implies the utter collapse of truth as a working concept: if truth is a matter of each individual’s view—which suggests that we accept contradictory truths, since there is nothing external to the individual by which we can verify the truth—then truth, logically, ceases to exist. We must avoid this skeptical position at all costs, for the erasure of truth leads not only to the impossibility of any agreement, but also to the impossibility of any disagreement. When constructively pursued, disagreement brings with it invaluable results by requiring each individual to respond to ideas and arguments he would otherwise have ignored, either intentionally or unintentionally. In short, disagreement plays the vital role of keeping dogmatism in check. Although we may not be able to entirely break free of subjectivity, it is nevertheless worthwhile to find ways to bolster our idea of truth such that it conforms to the highest possible standards of verification.

To this end, we suggest that crucial to the evaluation of any truth are three kinds of verification: empirical, experiential, and logical. Today, most people only apply one of the three at any given moment.

Some hold that empirical verification is the gold standard of any and all truths. These are the strict materialists who maintain that seeing is the only foundation for believing—loosely speaking, this is the “scientific” point of view. Among this cohort are the academicians who rebuffed our efforts to collaborate.

On the other hand, there are those who fall into the experiential camp. This group is largely comprised of people who know little to nothing of how knowledge is evaluated and shared, preferring instead to appeal to their own sense of reality. Their reasoning is largely emotional. These include the city fathers who withdrew endorsement and support of our conference, taking on faith the judgment of others.

Finally, there are the others who prioritize logic but who, without appealing to both experiential verification and empirical verification, can easily get lost in the clouds.

Each form of verification is in fact crucial to any serious inquiry. Through empirical verification, we are able to see whether the claim conforms to the body of knowledge that we already have. Experiential verification allows us to test whether the claim conforms to our own individual experience and makes sense according to our paradigm of reality. This is not mere subjectivism: we cannot discount human experience, for it is the starting point of any and all knowledge. This explains why the third kind of verification—logical verification—is necessary. Because our experiences may be partial, or even deceptive, we must abide by what is logical, even if it is not always supported by personal experience.

Each kind of verification acts as a check on the others. A robust standard of truth thus maintains that a true proposition is one that satisfies all of empirical, experiential, and logical verification. If a claim fails in one area it is a hypothesis, not a true proposition. There is nothing wrong with a hypothesis—at the heart of all inquiry, it is a working claim that is constantly being tested and revised. There is nothing false in a hypothesis but, equally and most importantly, it is not yet true.

Such a rigorous standard for judging a proposition draws a firm line between hypothesis and truth—thus restoring the latter to its rightful place. As a result, we could end up with access to fewer truths than we might otherwise have thought, but this is not a negative. The goal of inquiry is not to give all our ideas and opinions the status of truth, but to accord such status only to those ideas that have been hard won, and which have the ability to endure after we no longer have a stake in the discussion.

In our quest for truth, therefore, we must deal with the imprecision, peculiarities, and prejudices of the human mind and seek to diminish their agency. This we found as we assembled our conference and encountered opponents dedicated to a consensus that abolished inquiry about alternative interpretations. For example, one of the city councilors with whom we interacted accused certain speakers of harboring ideas that denied the impact of climate change—even though the reality was otherwise. Neither the conference planners nor the speakers regarded themselves as deniers of climate change or its threat to the quality of life, the infrastructure, the economy, and myriad other affairs. Several speakers were skeptics and challengers of the consensus; as analysts with alternative perspectives, they came armed with data that they submitted to public scrutiny. Even so, their opponents in public life and academia sought to demonize them and to annul their messages before they were uttered.

Deniers—or skeptics?

As our conference experience suggests, zealous consensus advocates tend to assign all challengers to the category of denier. If, as it seems, this proclivity is sometimes misguided, how

do we definitively distinguish between denial and skepticism? Hence, our third question: What is the difference between deniers of science and skeptics of science?

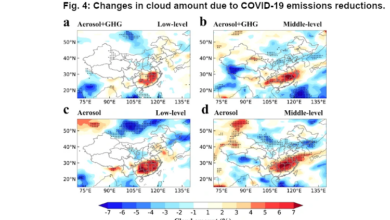

A topical example points to the answer. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an unprecedented opportunity to observe the interplay of new research findings with the scientific community, policy makers, the media, and the public. The rapidly evolving public health emergency created an immediate need for reliable information to guide policy and to aid medical decision making.

The entry of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine as putative therapies for the corona virus infection first gained traction in a letter to the editor of Cell Research (published online, February 2020). The letter described laboratory experiments in Wuhan, China, then the epicenter of the emerging pandemic. Testing five common anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agents against SARS-CoV-2 infecting cultured monkey kidney cells, the authors demonstrated that chloroquine had promising antiviral activity. Quickly following this report was an observational study by P. Gautret et al. (International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, published online, March 20, 2020) wherein 26 patients with test-proven COVID-19 were treated with hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin (a common antibiotic) and compared to 16 control patients treated at another hospital without hydroxychloroquine. The authors suggested that the hydroxychloroquine-treated patients efficiently reduced viral carriage when compared to the untreated patients. This thread of evidence led to widespread application of hydroxychloroquine to the therapy of patients with COVID-19.

Rick Bright, PhD, Director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), was a vocal proponent of allocating congressionally mandated funds for “safe and scientifically vetted solutions, and not for drugs, vaccines, and other technologies that lack scientific merit.” (CNN Politics, April 22, 2020). When demoted to a lesser position within the HHS, he alleged that this was retaliation for his challenging the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19: “Contrary to misguided directives, I limited the broad use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, promoted by the Administration as a panacea, but which clearly lack scientific merit.” He left government service in October 2020. Subsequently, multiple observational studies of hydroxychloroquine use appeared in the literature, most showing lack of efficacy, several indicating a higher risk of death.

This example illustrates the importance of the distinction between “science denial” and “science skepticism.” Dr. Bright was skeptical of the utility of hydroxychloroquine based upon, at the time, the absence of scientific knowledge confirming its efficacy and safety. He denied no science; he was victimized for rejecting the politically motivated belief in hydroxychloroquine as a therapy for COVID-19.

What characterizes science denial? In 2009, Chris Hoofnagle, a Ph.D. physiologist, published a blog in the Guardian that lists the features of denialism in scientific research: 1) alleging that scientific consensus involves conspiring to falsify data or suppress the truth; 2) citing fake experts or individuals while marginalizing, demonizing, or denigrating published experts; 3) cherry-picking atypical or even obsolete papers; 4) making unreasonable demands upon research, claiming that any uncertainty invalidates the findings while rejecting probabilities and mathematical models; 5) comparing apples and oranges, promoting false equivalencies among competing ideas, or drawing flawed conclusions from scientifically valid research. As this list demonstrates, there is clearly an element of intended obfuscation by science denialists, who often deploy propagandistic techniques to cripple the arguments of their rivals.

The skeptic is a different creature altogether. Some speakers at our conference and others who have published their concerns in various media belong to a cohort of individuals whose skepticism of certain scientific theories and resultant policy decisions offers an important service to the community. They demand rigor in scientific analysis, provide alternative interpretations of events, and enforce a critical reexamination of the facts. We carefully vetted the credentials of our conference speakers who, to support their arguments, came with data published in peer- reviewed literature. Nevertheless, they were subjected to the same berating accorded the charlatans of science denial. In The Climate Skeptics (2004), Stefan Rahmstorf of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research attempts to disqualify the skeptics’ influence, arguing that climate researchers end up in a compromised position whether or not they engage in debate. He then contradicts himself by calling for a public exchange of scientific ideas: “Extreme opinions of individuals or dubious arguments cannot prevail where there is broad and open discussion among specialist scientists.”

Exactly! Was that not our stated purpose in holding the conference?

Unlike science denial—which actively challenges or passively ignores accepted science, using dissuasion, disinformation, or propaganda—informed skepticism may bespeak a plausible alternative interpretation of the evidence. For an expert scientific authority to assume a priori that the skeptic has nothing of value to offer seems to us an intellectually undignified position to assume. Closure of dialogue with those articulating any skepticism for AGW is explicitly unscientific.

Motivations for consensus advocacy

Why would traditional academic scientists stonewall inquiry challenging the consensus? According to Fostering Integrity in Research (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017), the answer is as banal as human nature, with the usual weaknesses at play: for example, fear of impugning the views of one’s colleagues, losing esteem in one’s discipline, or diminishing the importance of one’s research; and desire for personal gain, whether in the form of money, power, promotion, grants, sponsorship, patronage, or prestigious employment. At their most benign, such motivations may be no more than annoyances among colleagues and supervisors; at their worst, they may contribute to scientific disinformation, misconduct, or fraud.

We conjecture that our academic opponents rejected participation in the conference as a consequence of their devotion to AGW consensus. Perhaps they perceived a number of our speakers as direct threats to a career’s worth of work. Or perhaps they just preferred to vilify our lecturers rather than to engage in discussion.

We believe that the city fathers who withdrew endorsement of our meeting were simply following the persuasive power of the AGW consensus advocates. It is doubtful that they, not being experts, discerned any advantage to disputing the consensus. At worst, they can only be accused of lacking the courage to assail the controversy.

The cost of consensus: four lessons

Our experience of creating a conference of honest and balanced inquiry for the community furnished the following lessons:

First, the academics with whom we sought a collaboration clearly evinced a climate change chauvinism favoring a narrative of AGW that excludes discussion of alternative understandings. We were perhaps naïve in our belief that experts representing both AGW advocacy and skepticism could, on equal footing, share a panel.

Second, in the minds of climate change advocates, denier and skeptic are indistinguishable appellations. Under the regime of a “97 percent scientific consensus,” skepticism is given no quarter. The unwillingness of card-carrying scientists and experts to engage in the climate discussion with skeptical scientific peers and professionals was baffling to us; the vindictiveness of the AGW proponents was a shock.

Third, the fractious demeanor shown within the climate consensus group translates equally well to other belief federations. The COVID-19 pandemic has been witness to its share of scientific disinformation and bias. There are undoubtedly smaller tempests in other teapots.

Finally, empiricism having shown itself to be a surer guide than speculation, truth in science requires consideration of all observations, and these must be as readily available and unfiltered as evidence presented to a jury, whether by saints or scoundrels, whether credible or not. A poor substitute for such truth, consensus advocacy exacts its price from society and culture. Without unrestricted access to information and opinion, we are left under the control of the anointed of the day—all those who, with apparent impunity, erect barriers to the imagination and innovation that advance knowledge. Truth reposes with us individually—a collective is never accountable.