The Jackie Robinson Museum focuses on Civil Rights and Baseball

Jackie Robinson’s family home in Stamford, Conn., has a gallery of trophies, artifacts and a large scrapbook commemorating his many accomplishments. His son David Robinson recalled in an interview how a wall holds photographs and plaques depicting his father’s success in sports. Another wall – with a collection twice as large – highlights his father’s social activism, something that means much more to Jackie Robinson and his family.

The evocative properties of that cave, which emphasize social activism rather than sport, along with many similar artifacts, have been moved to a new museum in Lower Manhattan dedicated to the legacy of one of the heroes. most important object in American history.

The new Jackie Robinson Museum – New York City’s first museum devoted largely to the civil rights movement – will hold a ribbon-cutting ceremony on Tuesday and open to the public on September 5, allowing visitors to guests immerse themselves in the legacy of Robinson and his widow, Rachel, in a larger, modernized version of the family home, in the same spirit of using sport as a vehicle to promote progress. society.

“But the collection is a thousand times bigger,” said David Robinson, who lives in Tanzania but was in New York for his mother’s birthday and the opening of the museum. “Some of the things we grew up with now have great historical significance, and museums are places where people can see it, and so much more. It would be a miracle of modern information delivery.”

Rachel Robinson, who turned 100 last week, will cut the ribbon to inaugurate an organization she has long envisioned as a hub for people to learn about the courageous work her husband has done, joining hands with her, to help transform American society through the integration of Major League Baseball, and many other ventures.

Jackie Robinson, who was a young Kansas City Monarchs star in the black leagues, broke the color barrier in the white majors on April 15, 1947, when he debuting the National League’s Brooklyn Dodgers team. He immediately became a symbol of hope for racial equality in the United States, but as museum-goers will discover, Robinson’s tireless work to break down barriers began very early on. long before. And the job continued long after he retired as a player after the 1956 season.

Visitors will find that while Robinson was in the military during World War II, he successfully promoted Black soldiers to be allowed into the officer training program, which he completed in 1943. and became a lieutenant. They will learn how, after Robinson retired from baseball, he broke barriers in advertising, broadcasting and business, how he set up a bank to help companies. black population, so are often excluded from the basic, guaranteed loans.

They will also be inspired, museum organizers hope, by his and Rachel’s work along with many of the pillars of the civil rights movement, including Father Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers and Whitney Young, whom David Robinson remembers visiting with his parents at the house in Stamford.

“It was such an important historical period that the museum wrapped it up,” said David Robinson. “If we don’t remember that struggle, we will lose touch with an important period in American history that could help shape us today, and it is a tribute to all of us. who fulfilled my mother’s wish and made it come true.”

One of those people is Della Britton, the tireless president and CEO of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, a nonprofit founded by Rachel Robinson to continue her husband’s legacy through college education and scholarship. study for 242 students per year.

The museum has begun online programs with schools across the country and is in sync with Rachel Robinson’s ultimate goal, hoping to be a beacon of encouragement and support for the next wave of activists. leader in the fight for social justice.

“When we first went on a mission to build this museum, Rachel said to me, ‘I don’t want it to be simply a temple to Jack, I want it to be a place to bring people together. and continue the dialogue around the hardest things. Britton said. “That’s what has kept me here for the past 18 years. And as we have grown politically in that time, it seems even more compelling and important.”

Getting the museum up and running is a challenge. Funding problems stemming from the 2008 financial crisis, followed by the pandemic, and worldwide supply chain problems, have forced the museum to delay its reopening, Britton said. many years. The fund raised $38 million of the $42 million it sought to build the museum, of which $25 million went into construction.

Now, the museum is finally ready to open, complete with 4,500 artifacts and 40,000 historical images. It has more than 8,000 square feet of permanent exhibition space in a prime location on the border of TriBeCa, and another 3,500 square feet of classroom and gallery space.

A study done on behalf of the museum in 2018 estimated between 100,000 and 120,000 visitors per year, Britton said, but the museum is preparing for more, especially since there is currently no museum. No other museum like in New York.

“In a city where Lady Liberty greets you, there is no other civil rights museum,” Britton said. “That is very important.” The museum boasts a fascinating collection of artifacts and exhibits connecting Robinson’s sporting success with his pioneering civil rights work. Visitors will be able to see the letters he exchanged with Branch Rickey, the Dodgers president and general manager, who originally signed Robinson, reflecting their complicated relationship.

They can also learn about some of Robinson’s friends and allies, including Ralph Branca, the Dodgers pitcher, Robinson’s first teammate, and Hank Greenberg, a Jewish slugger for The Detroit Tigers, who have experience fighting anti-Semitism in baseball and were the first opposing player to offer words of support and encouragement to Robinson. There was an exhibit about John Wright, a little-known pitcher of the black league, to whom Rickey signed three months after he signed Robinson. Along with Robinson, Wright was the victim of racist abuse in the minor leagues. He eventually returned to Homestead Grays without a chance to break into the Dodgers.

The museum has also secured a uniform and bat that Robinson used in 1947, the Rookie of the Year Award, his National League Most Valuable Player Award since 1949, the plaque His original Walk of Fame, his Presidential Medal of Freedom, and more.

Each day, an electronic ribbon parade will present a question of the day for visitors and school groups to generate conversations about race.

“It could be something like, ‘Is Colin Kaepernick right to kneel during the national anthem?” Britton said. “The idea is to start a conversation and get people thinking.”

Britton and family will hold a ribbon-cutting ceremony on Tuesday, and guests will include tennis pioneer Billie Jean King; filmmaker Spike Lee; Eric Holder, former attorney general of the United States; former players CC Sabathia and Willie Randolph; and John Branca, board member and grandson of Ralph Branca.

On a recent tour, Britton highlighted many of the museum’s unique features, including the holographic Ebbets School highlighting where many of Robinson’s accomplishments take place, as well as things like the hot dog stand where Rachel Robinson warms up. bottle for Jackie Robinson, Jr., their eldest son, who passed away in 1971.

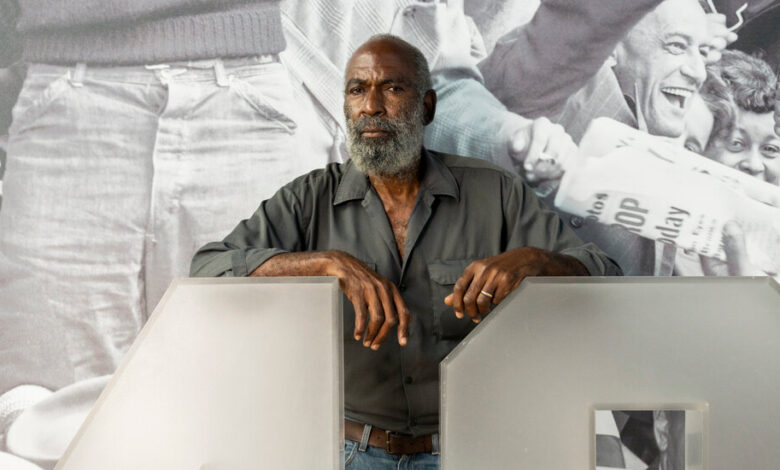

David Robinson, born in 1952, is too young to remember his father’s playing days. His fondest memories revolve around family dinners, fishing trips and especially golf, where David loved to be his father’s caddy.

“We played where we could, in segregated and discriminatory Connecticut,” recalls David. “He can only be a guest of a European at those golf clubs. But we were traveling to the Caribbean, Spain. It’s nice to be around.”

Other important anniversaries include gatherings at home with other civil rights leaders and lively discussions about how to improve the lives of millions of Americans – a key theme the museum strives to convey. In that way, David, her sister Sharon, and their mother believe Jackie Robinson will see the museum as an important extension of a shared heritage.

David Robinson recalls: “Very rarely did he say, ‘I’. “He would say, ‘We did some great things.’ But I think he’ll be thrilled to have his achievement shown in terms of American evolution, to try and inspire action today.”