The Coming Future of Electric Vehicles: Something Here Doesn’t Complement

Supposedly, we are rapidly moving towards a carbon-free, all-electric future. But has anyone done the math to see how this adds up?

I’m making a niche for myself as someone doing a few simple calculations to check if our central planners’ grand plan makes any sense. So far I have taken that approach to energy storage question for wind/solar grid backup, and above that, the plans of the central planners are certainly not the best fit. But the energy storage question, although not involving math beyond basic arithmetic, has some complications. What about something a little simpler, like: If we convert our entire fleet of cars to all-electric cars, where will the electricity come from?

With the current big push to phase out internal combustion vehicles and replace them with electricity, surely someone has calculated to ensure that electricity supplies will be plentiful. Actually, that’s not the case. Again, the central planners didn’t know what they were doing.

Several things in the recent news make this matter highly topical. First, in the days just before Christmas, much of the country experienced a severe frost. Serious, that is, but not record breaking. Most places where it was very cold in those days had even colder temperatures in the past, not necessarily every year, but many times over the course of decades. Second, some utilities find they don’t have enough electricity to meet demand and have had to put their customers in constant power cuts, even in the face of freezing cold temperatures. Includes examples of utilities that cause rotating outages during severe cold Duke of Energy (includes most of North and South Carolina, and parts of Florida, Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky) and TV (includes all of Tennessee and parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky). Both those gadgets and many more have spent the past decade and more shutting down reliable coal power plantsand built more wind turbines and solar panels, along with some (but obviously not enough) natural gas plants, to replace.

To this day, electric vehicles make up only a tiny fraction of all vehicles (less than 1% in the US, Reuters said as of February 2022), especially in these Midwestern and Southern states. However, even with minimal electricity demand coming from electric vehicles, major utilities ran out of power when an unusual cold snap hit.

And now, where will things go in the near future? The Wall Street Journal had a big article with January 1st (it appeared in print on January 3rd) about the upcoming electric car craze, headline “The switch to electric vehicles triggered the biggest auto plant construction boom in decades.” The gist is that the industry is preparing to build factories at breakneck speed to make the upcoming electric car available to everyone. Excerpts:

The U.S. auto industry is entering one of its biggest factory building booms in years, a surge in spending driven largely by a shift to electric vehicles and new federal subsidies to boost sales. push U.S. battery production. According to the Center for Automotive Research, a Michigan-based nonprofit, about $33 billion in new car plant investments have been committed in the U.S. through November, including money to build new cars. new battery assembly and manufacturing facility. . . . The capital outlays equate to a collective bet by the auto industry that buyers will embrace battery-powered models in large enough numbers to support these investments. According to consulting firm AlixPartners, the global auto industry plans to spend a total of $526 billion on electric vehicles through 2026.

Rub! It’s the industry’s total transformation, from internal combustion engines to electric batteries. And if you look at the manufacturers’ own websites, most of them say they’re committed to a quick transition to electric vehicles, with all internal combustion engine production phased out soon. This is GM on ‘road to an all-electric future’ (until 2035); and this is Ford vows to ‘lead America to electric vehicles’ (50% by 2030!). Many other manufacturers are making similar claims.

OK, so how much electricity will this take? I’ll start with this utility (if it’s a bit complicated) chart from the US Energy Information Administration shows the production (by source) and use (by sector) of all energy in the United States for 2021 (I haven’t found a chart for 2022.):

Here are a few key numbers from this chart:

- Total energy consumption in the US in 2021 is given at 73.5 million Btus.

- Of the 73.5 million Btus consumed, only 12.9 million Btus was in the form of electricity. That’s just 17.6% of total energy consumption.

- Most electricity is consumed in the household, commercial and industrial sectors, and almost none (less than 1%) in the transportation sector.

- The transport sector consumes 26.9 million Btus of energy. That’s 37% of total energy consumption — and more than double total power consumption in all areas.

OK, but transportation isn’t just about cars. It also includes everything from planes to cargo ships to ocean freight. Which part of that 26.9 million Btus of energy in the transportation sector including cars and light trucks (like SUVs and pickups) is supposed to be about to be electrified? Looking around, I see something called Transportation Energy Data Book, produced by Oak Ridge National Laboratory — another division (such as EIA) of the United States Department of Energy. Here are two key takeaways from the “Quick Facts” introduction: (1) “Oil will account for 90% of the energy used in U.S. transportation by 2020,” and 2) “Automobiles and light trucks accounted for 62% of U.S. transportation gasoline use in 2018.”

Assuming that those percentages approximate to 2021, then cars and light trucks consumed about 26.9 x 0.9 x 0.62 = 15.0 million Btus in petrol or diesel form by 2021 — more than all of the energy consumed in the country in 2021. that year in the form of electricity.

So have we now shown that converting all cars and light trucks to electric will require more than twice the size of our power generation system? Unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple. There are a few other factors that need to be taken into account. Unfortunately, these extra factors are not very precise and can only be approximations:

- Electric vehicles are about 85-90% efficient at converting the energy stored in the battery into vehicle motion. That compares with the efficiency of only about 15-25% of ICE vehicles. That is a big difference.

- However, two other factors make up for that advantage. One is that an electric vehicle’s battery loses about 15% of its charge during the cycle between charging and discharging. The second is that the power generation process in a power plant is between 35-50% efficient, depending on the type of power plant. Some of the latest power plants even claim efficiencies up to 50%, but note that the EIA chart above shows an overall efficiency of US power generation of 35% (including losses in electricity). Transmission).

Put these factors together and here’s the calculation:

For internal combustion cars, if you start with 10 Btus of energy in gasoline, you will get about 2 Btus of movement from your car.

For electric vehicles, if you start using the same 10 Btus fuel you will get 10 x 0.35 = 3.5 Btus of usable electricity, 3.5 x 0.85 = 3.0 Btus electricity in your battery after charging loss and 3.0 x 0.87 = 2.6 Btus of motion from your vehicle.

So overall, and remember this is an approximation, a fleet of all-electric cars and light trucks can run on about three-quarters (2 divided by 2.6) of Btus. of energy input compared to a comparable fleet of internal combustion engine vehicles. Instead of the annual 15 million billion Btus we use for our current ICE vehicles, we could theoretically reduce it to 11.25 million Btus, which would make 11.25 x 0, 35 = 3.93 million Btus of electricity to run the vehicles.

Recall that the amount of current electricity produced annually in the United States, from the chart above, is 12.9 million Btus. So, 3.93 million Btus of additional electricity would correspond to about 30.5% addition to the current capacity of our generation system.

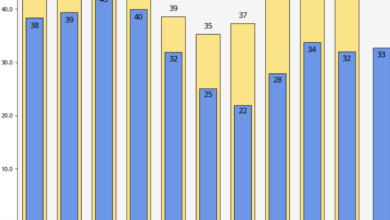

Are there any plans underway for anything like that? Here’s another chart from the EIA showing the forecast for growth in US generating capacity through 2050, from Annual energy outlook 2022:

Essentially, following the current recovery from the Covid 2020-21-induced decline, they predict a visible 1% annual increase in consumption. The “high economic growth” and “low economic growth” scenarios are not significantly different from the median “reference” case. This growth includes the growing demand for everything from the growing population and every new type of electrical appliance that could be invented during this period. And note that this forecast, at least in previous years, is largely based on utilities’ plans to add capacity — or not. And to the extent anyone is adding capacity, it’s likely wind and solar, which would be completely useless to charge these vehicles on quiet nights and many other times.

So where is the surge in generating capacity to support the 30% or so additional electricity demand to electrify all cars? It certainly doesn’t look like it to me like it’s there.

For the full story, click here.