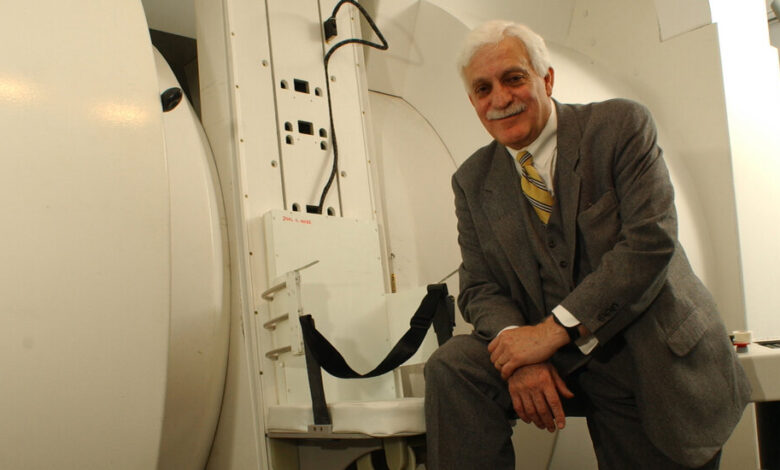

Raymond Damadian, Inventor of the First MRI Scanner, Dies at 86

Dr. Raymond Damadian, who built the first magnetic resonance imaging scanner, revolutionized doctors’ ability to diagnose cancer and other diseases – but to whom he was disappointed when he saw the Nobel Prize in science the school behind it belongs to two other people – passed away on 8/8. . 3 at his home in Woodbury, NY He was 86 years old.

Daniel Culver, a spokesman for the Fonar Corporation, founded in 1978 by Dr. Damadian, said the cause was cardiac arrest.

Since Dr. Damadian and his research assistants completed the construction of the first MRI scanner more than 40 years ago, it has become an essential medical device, allowing doctors to look inside in the human body with more detail and higher resolution than X-ray and CT. scanning provides, without exposing the patient to harmful radiation like many other technologies.

“We take it for granted now, but the MRI is absolutely breathtaking,” Dr. Burton P. Drayer, chair of the radiology department of the Mount Sinai Health System in Manhattan, said in a phone interview. “MRI is better at detecting cancer, especially in the brain and spine.”

But the question of who owns the ideas, and the equipment, has been a contentious issue from the start.

Two scientists whose research contributed to MRI technology were subsequently awarded the Nobel Prize, an honor that Dr. Damadian felt should also be given to him. And it wasn’t long before his machine was on the market when a handful of large corporations began to produce their own versions, leading to years of court disputes over patent rights.

The vision of scanning the human body without radiation came to Dr. Damadian in the late 1960s, he says, when he was working on nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy – until, Dr. Damadian said. It is still used to determine the chemical makeup of test tube contents – at Downstate Medical Center (now SUNY Downstate University of Health Sciences) in Brooklyn.

Working with mice, he discovered that when tissues were placed in a magnetic field and subjected to a pulse of radio waves, the cancerous ones emitted radio signals that were significantly different from those of healthy tissue. .

He published his findings in 1971 in the journal Science and patented three years later for a “device and method for detecting cancer in tissues”. It took 18 months to build the first MRI machine, originally called a nuclear magnetic resonance scanner, or NMR Its first scan, on July 3, 1977, was of Lawrence Minkoff, one of the Dr. Damadian’s assistant – a vivid and colorful image of him. heart, lungs, aorta, heart chambers, and chest wall.

“After the initial idea of the NMR body scanner, we planned to be the first to complete it,” says Dr. Damadian in his book, Gifted Minds: The Story of Dr. Raymond Damadian, Inventor of MRI,” published in 2015, which he wrote with Jeff Kinley. “Failure to do so means we may be denied recognition of the original idea.”

But the technology behind MRI has several founding fathers.

Acknowledging that he was inspired by the work of Dr. Damadian, Paul C. Lauterbur of the State University of New York at Stony Brook have found a way to convert radio signals emitted by tissue into images. And Peter Mansfield of the University of Nottingham in the UK developed mathematical techniques to analyze the data, making the process more realistic.

Using techniques he pioneered, Dr. Damadian’s company, Fonar, based in Melville, NY, produced the first commercial scanner in 1980.

But Fonar soon faced competition from major corporations such as General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, Siemens, Hitachi and Philips.

Dr. Damadian sued them all for patent infringement. He lost his case to Johnson & Johnson when a federal judge in 1986 reserved a jury verdict in Fonar’s favor.

The judge, Dr Damadian said, “did all he could to surround us in court.”

He won his biggest legal victory in 1997, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Commonwealth confirmed a lower court ruling of nearly $129 million in damages and interest from the United States. GE. He also won smaller settlements from other manufacturers.

Raymond Vahan Damadian was born on March 16, 1936 in Manhattan, and grew up in Forest Hills, Queens. His father, Vahan, an Armenian immigrant from Turkey, was a newspaper photoengraver; His mother, Odette (Yazedjian) Damadian, is an accountant.

Raymond studied violin for several years at Juilliard but turned to science when he received a Ford Foundation scholarship to attend the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He majored in mathematics there and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1956. He received his medical degree four years later from Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx and later became a PhD student at Harvard, where he became acquainted with nuclear magnetic resonance. Technology.

During his time at Downstate and later at Fonar, Dr. Damadian got to know Dr. Lauterbur, a chemist also working on MRI imaging and with whom he shared the National Medal of Technology.

In “Gifted Mind”, Dr. Damadian acknowledges that Dr. Lauterbur “realized that the differences in NMR signals in normal and diseased tissues that I detected could be used to build a picture (Picture).”

He wrote a letter to the American Medical Association, claiming that “some unscrupulous science pilot is trying to steal my whole life”.

He then spent several hundred thousand dollars on an advertisement in six major international newspapers. Title “Shameful mistake must be corrected” advertising that the Nobel committee unjustly denied him the prize.

At the end of the ad, he offers a coupon, addressed to the Nobel Committee in Physiology or Medicine, for the reader to tell the committee that “FACT must have a place,” and it will add him. I am the third recipient of the award. .

Dr Hans Ringertz, chairman of the Swedish committee that awarded the prize that year, did not comment on Dr Damadian’s statement but told The Times that nothing will prevent Dr. Damadian from being nominated in the future.

A year later, Dr. Damadian received one of two annual Bower Awards given by the Franklin Institute, a science museum in Philadelphia. He was commended for his business leadership.

Dr. Bradford A. Jameson, professor of biochemistry at Drexel University and chair of the committee that selected the winners, said: “There is no question about this. “If you look at the patents in this area, they’re his.”

Dr. Damadian later said that he was no longer interested in the Nobel dispute. But he told The Times, “If people want to revisit history beyond the truth, there’s not much I can do about it.”

Dr. Damadian continues to innovate. He created open MRI machines, which help alleviate the claustrophobia that patients may experience during scans when they are moved slowly through a tight tunnel, as well as portable and stand.

In recent years, he has focused on research that includes imaging brain spinal fluid as it flows to the brain.

Fonar has built and installed about 500 MRI scanners, but today it focuses on managing imaging centers in the United States and maintaining existing scanners.

Dr. Damadian is survived by his daughter, Keira Reinmund; his sons, Timothy, president and chief executive officer of Fonar since 2016, and Jevan; nine grandchildren; three great-grandchildren; and an older sister, Claudette Chan. His wife, Donna (Terry) Damadian, died in 2020.

In 1982, when the industry he helped create was in its infancy, Dr. Damadian told Newsday he hadn’t lost his inventor’s enthusiasm for what lay ahead.

“In 1977, I knew my machine could become a reality,” he said. “But until then, it’s like building a model airplane. Now I know it’s real.”

Kenneth Chang contribution report.