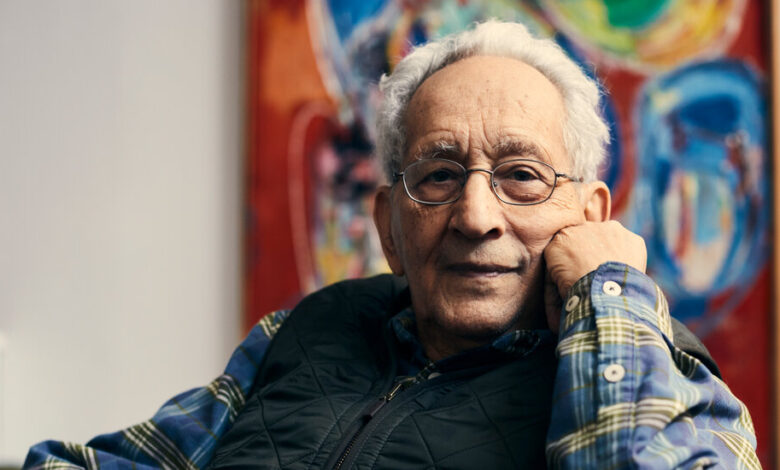

Frank Stella, Distinguished Artist and Master of Reproduction, Dies at 87

Frank Stella, whose pinstriped “black paintings” of the late 1950s shut down Abstract Expressionism and pointed the way to an era of exciting minimalism, died Saturday at home exclusively in Manhattan’s West Village. He was 87 years old.

His wife, Dr. Harriet E. McGurk, said the cause was lymphoma.

Mr. Stella was a dominant figure in postwar American art, a relentless, restless innovator whose explorations of color and form made him a prominent, discussed presence. commentary is constantly and continuously on display.

Few American artists of the 20th century came to his éclat. He was in his 20s when he got big black painting – precisely delineated black stripes separated by thin lines of blank canvas – took the art world by storm. Austere, self-referential, ambiguous, they cast a chilling spell.

Writing in Art International magazine in 1960, art historian William Rubin declared himself “almost enchanted” by the “strange, magical presence” of the paintings. Time only ratifies consensus.

“They remain among the most provocative, unforgettable paintings in the recent history of American Modernism,” critic Karen Wilkin wrote in The New Criterion in 2007. In 1989, “Tomlinson Court Park” , a black painting from 1959, sold at auction for $5 million.

Mr. Stella, a strict Calvinist formalist, rejected all attempts to explain his work. He believes that the feeling of mystery is a matter of “technical, spatial and motif ambiguity”. In an oft-quoted piece of advice to critics, he insisted that “what you see is what you see”—a formula that became the unofficial motto of the minimalist movement.

Over the next five decades, he proved himself a master of innovation. In the early 1960s, he enlivened the striped formula with vibrant colors and the picture has shape. At the end of the decade, he embarked on an ambitious project “Protractor line – more than 100 mural-sized paintings of overlapping half-circles in bright, sometimes fluorescent colors. The paintings, inspired by the simple measuring instrument in the title, “bring the entire abstraction of color to an almost baroque elaboration,” wrote Hilton Kramer in The New York Times.

Critic first exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in Manhattan in 1967, the series established Mr. Stella as “the god of the sixties art world, exalting a taste for reductive form , astonishing scale and exuberant artificial colors.” Peter Schjeldahl wrote in The New Yorker in 2015. Mr. Schjeldahl’s impact on abstraction, Mr. Schjeldahl added, “is like Dylan’s impact on music and Warhol’s impact on more or less everything.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, with great fanfare, Mr. Stella abandoned the flat picture plane, pushing his works away from the wall into assemblages bristling with curves, curves and loops. painted aluminum spiral.

These “maximalist paintings,” as he called them, were extroverted, cheerful and energetic, light years away from the brooding power of black paintings. They served as the calling card for Mr. Stella’s next phase, as a designer of major public works, such as the murals for the Gas Company Tower in Los Angeles (1991) and hat-like cover, made up of intricate aluminum ribbons, that he delivered. arrived in Miami in 1997.

Some critics found his work unattractive and programmatic. Harold Rosenberg, writing in The New Yorker in 1970, derided Mr. Stella’s ideas as “chessboard aesthetics.”

Reviewing the exhibition of his first paintings in The Times in 2006, Roberta Smith wrote that his work from the early 1980s was considered by many to be “capitally corporate.” Mr. Schjeldahl, in The New Yorker, dismissed much of the post-1970 work as “disco modernism.”

For most of her career, however, Stella rode a wave of critical acclaim and commercial success, fueled by dozens of one-man shows and retrospectives at museums all over the world.

Mr. Rubin, after becoming director of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, reaffirmed his admiration for Mr. Stella’s work by making him the youngest artist ever to honored in a museum retrospective in 1970, when he was 34 years old. In another unprecedented move, Mr. Rubin conducted a second retrospective in 1987.

Mr. Stella was the first abstract artist invited to give the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard in 1983 and 1984. (The lectures were published in 1986 as “Workspace.”) In 2015, hen the Whitney Museum of American Art reopens in its new building, in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, the opening exhibition is Stella retrospective.

In 2020, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Conn., presented “Frank Stella’s Stars,” a survey of the artist’s use of star forms in a variety of media, The culmination is the sculptures made in recent years.

Frank Philip Stella was born on May 12, 1936 in Malden, Mass., north of Boston, to Frank and Constance (Santonelli) Stella. His mother attended art school and later took up a career as a landscape painter. His father was a gynecologist and also a painting enthusiast.

Young Frank attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., where one of his instructors, the painter Bartlett H. Hayes Jr.Show him your work Hans Hofmann And Josef Albers.

At Princeton, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in history in 1958, Mr. Stella quickly became friends with the future critic. Michael fried and future color field painter Walter Darby Bannard.

Once again he got lucky with his teacher. William Seitzwho studied art history together, established an artist-in-residence program under which New York-based abstract painters Stephen Greene taught the school’s first courses in painting and drawing.

With Mr. Greene’s encouragement, Mr. Stella produced gestural paintings in the style of Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning. But after seeing Jasper Johns’s flag paintings at the Castelli Gallery in 1958, he adopted a colder, more analytical approach, deriving its effect from its precision. precision and repetition.

After his failure in the army – a childhood accident left him with disarticulation in the fingers of his left hand – he settled into a studio on the Lower East Side and began painting black, supplementing his income by paint the house.

In 1961, he married Barbara Rose, an art history student at the time but soon became a widely read contemporary art critic. The marriage ended in divorce in 1969; she passed away in 2020.

Mr. Stella is survived by his wife, Dr. Harriet E. McGurk, a pediatrician, and their two sons, Patrick and Peter; two children from his first marriage, Rachel and Michael; a daughter, Laura, from a relationship with Shirley De Lemos Wyse between his marriages; and five grandchildren.

Recognition comes at lightning speed. His work was shown in group exhibitions at the Tibor de Nagy and Castelli Galleries in 1959. Later that year, Dorothy Miller included four of his paintings in “16 Americans” at the Museum of Art. Modern Art, which purchased “The Marriage of Reason and Poverty.” .”

Over the next few years, Mr. Stella appeared in two important shows: “Toward a New Abstraction” at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan in 1963, and “Post-Painterly Abstraction” by the critic Clement Greenberg in Los Angeles is in charge. Angeles County Museum in 1964.

In 1965, he was chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, where he was the odd man out in a Pop-leaning lineup that included Mr. Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Jim Dine and Claes Oldenburg.

By that time, he had moved away from the ultimate aesthetic of black paintings, using commercial heatsink paint to create striped compositions in copper and aluminum and concentric squares based on primary colors. copy.

In his next series of paintings, he reconfigured his drawings to follow the shape of the stripes. This was the first step in a series of almost sculptural gestures that resulted in paintings that took the form of the “Irregular Polygon” series, with their vast expanses of uninterrupted color and extremely Protractor paintings. exuberant, his first best-selling paintings, the completion of which brought him to a turning point

“In the late 60s, I seemed to have hit a wall of very large Protractor paintings,” he told Sculpture magazine in 2011. “I didn’t think I could bring color and surface flatness to life. go further”.

In the 1970s, he began producing metal reliefs, evolving from the vaguely constructivist “Brazilians” series to the “Exotic Birds” and “Birds” series. Indian bird,” in which curls, swirls and graffiti-like markings protrude from an aluminum or mesh panel.

He went even deeper into three dimensions after visiting Rome in the early 1980s and studying the work of Caravaggio, whose intense chiaroscuro and profound spatiality had a profound impact on him. “The space that Caravaggio created was something that 20th-century painting could use: an alternative to both the space of conventional realism and the space of what had become conventional painterly nature. ,” he said in one of the Norton lectures he gave at Harvard.

Although the works are undeniably three-dimensional, he calls them “maximalist paintings” or “painted reliefs.”

“No matter how sculptural, three-dimensional or projected on a wall they may be,” he told The Times in 1987, “the essential way you look at them and deal with them is through the conventions of the disaster”.

Mr. Stella continued to explore his distinctive blend of painting and sculpture in the late 1980s and ’90s in an expanded series of 266 mixed-media reliefs based on “Moby-Dick,” featuring 135 subjects. themes he applies to his works, and in exuberant, sometimes raucous sculptures like “Kamdampat” (2002) and his computer-generated work “Scarlatti Kirkpatrick” series, which began in 2006.

A sculpture by Mr. Stella called “Jasper’s Split Star” (2017), constructed from six small geometric grids placed on an aluminum base, is Setting at the public square in front of 7 World Trade Center in November 2021.

His entire body of work was exhibited in the career-spanning “Frank Stella: A Retrospective” at the Whitney in 2015, a massive show for a towering if divisive figure, is as obsessed as Ahab in his attempt to reframe abstraction.

“Even the massive things, such as a monstrous pile of cast aluminum painted with wavy, stained patterns, display extraordinary, truly Melvillian ambition,” writes critic Jason Farago in Guard. “They are the work of an artist who did not want to, could not sit still.”

Michael S. Rosenwald Report contributions.