Americans insist on the EV’s 300-mile range. They are right

Americans like good things road trip. There’s nothing better than packing up, putting on some music and just — driving. For more than a century, summer dreams have been fueled by the limitless possibilities of a full tank of gas.

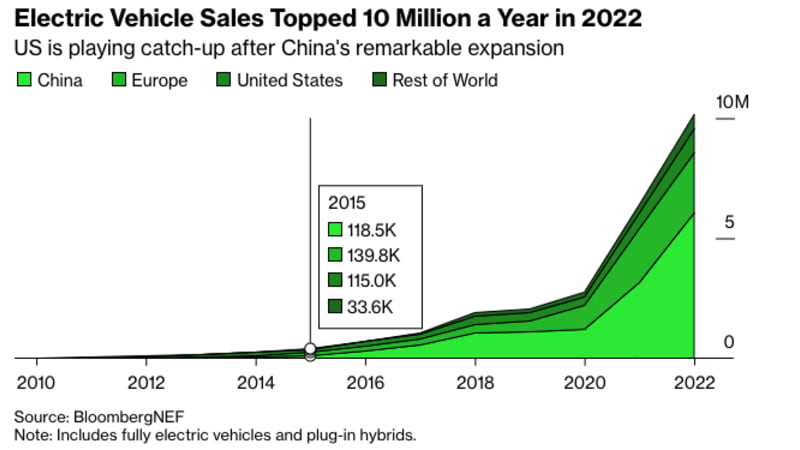

It is the mentality of “life and death, fly” that has also made the United States, until recently, slower to accept Electric Car. The open road is freedom, and the need to frequently stop and collect entry fees. Last year, plug-in vehicles accounted for less than 8% of new car sales in the US – far behind Europe’s 32% EV adoption rate And Chinaof 30% absorbed.

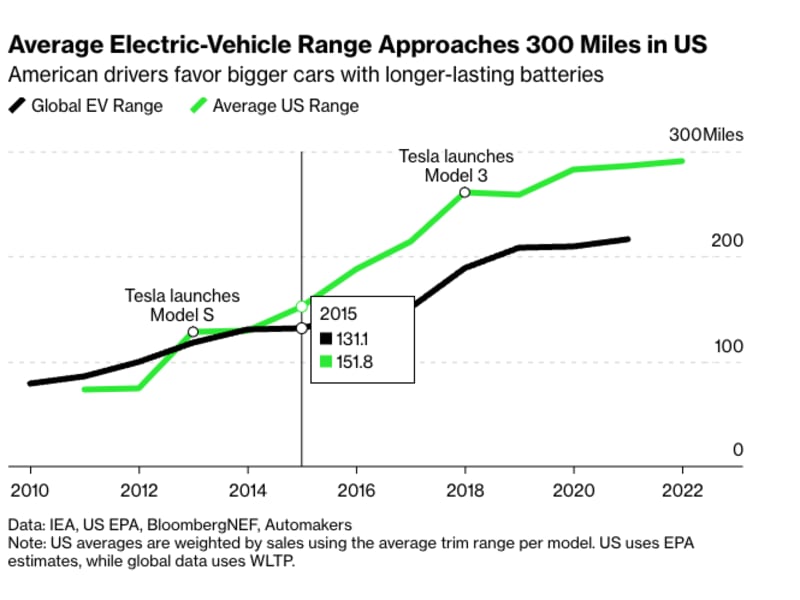

These places got off to a good start in part by embracing small trams with the battery and limited scope. In contrast, a survey conducted last year by green Bloomberg found that less than 10% of US respondents would accept anything less than 200 miles in range. Than recent numbering on the range for electric vehicles sold in the United States found that:

-

Americans are claiming the longest distances in the world, about a third more than the global average.

-

Average EV range is about to exceed 300 miles, an important psychological hurdle.

-

Many were quick to wave at this quintessential American excess. Average US commute time is 55 miles a day, think about it, so why need the extra miles? But American EV exceptionalism reflects a deeper understanding of range limitations than what consumers are typically recognised.

What affects EV range? Much

Americans spend more time in their cars than drivers in any other country. American road travel totals about 4 trillion miles a year, or about 14,500 miles/person – a third more than in any other country. That makes range anxiety particularly acute for Americans, who still have limited access to charging networks. For new EV buyers, figuring out the range you really need can be tricky.

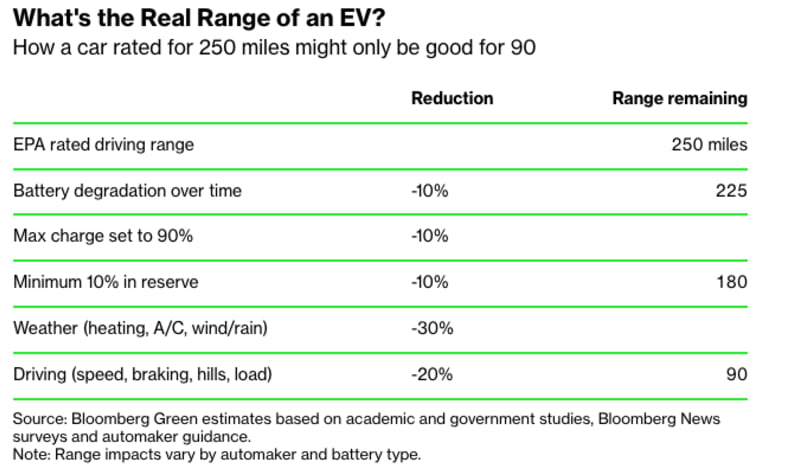

The problem is that a vehicle rated for 250-mile range doesn’t really offer a reliable 250-mile range. This number drops when you turn on the heater or air conditioner, or drive in heavy rain or wind. Stopping suddenly and often brake also eat weaning. Driving over 60 miles per hour, loading passengers and luggage, or using snowboards or bike rack.

Even in perfect conditions, drivers can’t count on all those miles to be rated. Just like with the gas tank, running out of battery runs the risk of you getting stuck, so it’s important to stock up on some mileage. Most batteries are also not fully charged — Tesla, for example, no more than 90% is recommended for daily charging. Ultimately, car buyers who plan to use their vehicle for many years will have to anticipate battery degradation over time, which will accelerate for smaller batteries.

All these factors together can easily reduce the range of use on a 250-mile battery to 90 miles.

On the surface, 90 miles seems like enough for an average day for most drivers. But days aren’t average: those times when you forgot to plug in your car at night, lost power, or needed an extra errand or check in with a friend on the other side of town.

Well, one might ask, it’s not a public thing charger is for?

A small problem with electric vehicle charging is that it often costs a lot Faster to add a few miles of charge to a large battery compared to a smaller one. That’s because longer-range batteries are made of materials better suited for fast charging. Also, when the battery is half full, the charging rate starts to slow down, so it takes less time for a smaller battery to travel the extra distance at full charge.

All of this means that 10 minutes of highway charging can add 160 miles of driving for a long distance. KIA EV6but only 32 miles to a base Leaf Nissan. Drivers must plan their stops accordingly.

Experienced electric vehicle owners learn to extend their range when driving long distances — for example, by keeping jackets zipped and heaters low when driving in cold weather, or slowing down degrees down to 60 mph on the highway instead of 75 mph when stretched to make it to the next charge. But mass adoption of long-range EVs requires fewer compromises.

Technology case for scope

Some argue that, with the world’s long-lasting battery supply, automakers should favor smaller electric vehicles or plug-in hybrids. The rationale is that we should divide what we have by the largest number of vehicles possible.

But this battery-maximizing strategy is based on the misconception that supplies cannot grow any faster, a notion that has been debunked by a century of mass production. Sure, it usually takes 2 to 3 years for a new battery plant to achieve success — and up to a decade to plan and develop new mines for essential minerals like lithium and nickel. But when demand is high enough, capitalism will find a way, and the profits from batteries in 2023 are too great to continue growing at the pace of 2013.

Right now, companies that mine and refine key minerals in batteries are increasing capacity at their existing plants and opening new operations around the world at the fastest rate in history. In the US alone, more than 58 billion USD has been invested in the battery supply chain in eight months to the end of March. The battery supply chain is expanding like a tidal wave, triggered by a seismic demand.

Another way for a growing battery supply is to use range-expanding battery chemistries that increase output by using the same amount of primary material. For example, a new one generation Battery suppliers are adding increasing amounts of silicon to the anode, which is the part of the battery responsible for storing lithium electrons after a charge. This simple tweak can instantly increase range by 20%.

That means that the same Panasonic or LG Chem plant designed to make enough batteries for 100,000 cars can suddenly hold 120,000 — with no major changes to the plant itself or its components. important minerals that the plant uses. These high silicon anodes will make their debut in luxury long-range vehicles, like the Mercedes G-Wagon 2025but they will ultimately increase vehicle range and reduce costs across the industry.

This model is typical of successful technologies, from cell phones to solar panels. Innovation starts in the high-end markets, and over time, economies of scale will bring it to the masses. In this way, US range enthusiasts can become the driving force in reducing battery costs globally.

Environmental case for scope

Another argument against large batteries is that they add significant environmental costs to electric vehicle production. Massive electric vehicles like the 400-mile Chevy Silverado pickup that will launch later this year have the same environmental impact as a gas-powered car. Honda Civicbased on electric vehicle researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In other words: If everyone transactions in small internal combustion engines for giant electric vehicles, we’re not going to make much environmental progress.

But few consumers are doing business in citizen for Silverados, or Volkswagen Jetta because Ford F-150 lightning. If they can’t convince America’s suburban cowboys to give up on pickups, they might as well ditch the internal combustion engine. Look through any Walmart parking lot in the US and imagine if every giant SUV and truck has been replaced with a fuel saver Toyota Corolla. That’s the scale of environmental achievement inherent to long-range EVs. And the environmental savings will only increase as batteries become more efficient and more grids run on renewable energy sources.

Another thing to consider is the magic of battery recycling. While lithium-ion battery recycling efforts are still in their infancy, that’s only because very few electric cars have reached the end of their useful life. Electric vehicle battery recycling is a profitable business, and about 95% of vital minerals can be recovered. Anyone buying an electric vehicle today can expect that the vast majority of their batteries will be made from newly mined materials at a negligible environmental cost. But anyone buying an electric vehicle today can expect those materials to eventually be recycled into someone else’s electric vehicle.

Better walking

Just to be clear: There are a lot of Americans who think smaller cars and smaller batteries are great. Those vehicles, for example, could be perfect for short city trips in temperate California. In addition, many people should absolutely bike, walk, and use public transport. If America’s cities did more to accommodate these, we would all be healthier and happier because of it.

But walkable cities aren’t what the average freedom-loving American is thinking about when looking for a new electric car on the market. Most consumers’ primary concern is how much it needs to fit into their lifestyle — and how much they can afford.

Finally, the big battery boom is working: As the U.S. hits the 300-mile range standard, electric vehicle use is starting to grow faster than other major markets (driven in part). by subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act). This year, sales will grow 73%, according to the latest estimates by BloombergNEF. That growth is more than twice as fast as China and four times faster than Europe.

Consumers are not stupid. It’s not a lack of understanding about how much we drive that prevents Americans from choosing lower-range cars. In fact, it is the knowledge of how deeply we depend on our means that drives Americans to demand such a wide range of activities.

Related videos: