A turnaround in stem cell transplants could help blood cancer patients

“It’s exciting that we were able to do that,” Shlomchik said.

“This is an important first step,” agrees Nelson Chao, head of the Division of Malignant Hematology and Cell Therapies at Duke University, who was not involved in the work. It’s hard to retain the benefits of a standard stem cell transplant without dangerous overactivity in the immune system, says Chao. These results add steam to a move towards refining grafts to combat chronic GVHD, he said: “Graft engineering is the future of all this.”

Cathy Doyle was one of 138 people with blood cancer participating in the clinical trial.

Photo: Michael GallagherIn 2020, nearly 475,000 won people are diagnosed with leukemia, a cancer that affects blood cells, according to the global cancer database Globocan. More than 300,000 people died from the disease that year. AML is just one form of leukemia, but it makes up more 11,000 dead each year in the United States.

Blood and marrow transplants have been considered a treatment for leukemia for nearly 70 years. They are an invaluable step after chemotherapy and radiation nuclearize the machines that make one’s cells. “You can rescue that toxicity by giving the stem cells back in the blood,” says Shlomchik. “So now you can deliver doses of chemotherapy that the person will die from.”

But very early on, doctors noticed a dangerous immune response. Then, in the 1990s, at the very beginning of his career in hematology, Shlomchik recalls coming across a study that made him realize the power of T cells, a type of white blood cell important to immune function. These relapsed cancer patients went into remission after having the cells transplanted. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is amazing,’ he said. He called his brother, Mark, an immunologist, and the two arranged to investigate the biology of the T cell to find a way to address chronic GVHD.

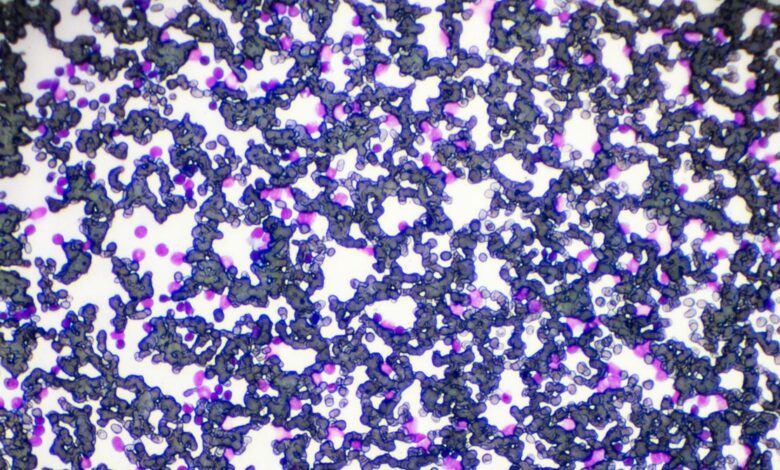

By 2003, the brothers had discovered, in experiments with mice, a subset known as memory T cells. did Not Activated Chronic GVHD. Memory T cells are immune cells that have learned, from exposure, to recognize a particular pathogen. They are a kind of immune veteran compared to “naive” T cells, which have not yet developed any special detection skills. Naive T cells are the real troublemakers.

In 2007, Marie Bleakley, a pediatric oncologist and a blood and marrow transplant physician now with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, began an effort to translate Shlomchiks’ work from mice into mice. people. Combined group learned how separates naive T cells from memory T cells, essentially by shedding donor blood through a special filtration system.

They’ll start with a bag of donated fluid — technically a concoction harvested from a donor’s bone marrow that contains blood and immune cells. They will hang the bag two feet above the magnetic tube on a machine called the CliniMACS. Inside the bag, they will also place small iron particles, each of which is attached to an antibody designed to find and attach to naive T cells. As the fluid runs through the pipe and passes through more magnets on the machine, the naive cells stuck to the iron particles will stay. What’s left at the bottom will be a mixture of memory T cells. “It’s simple but elegant,” says Bleakley.