A bigger picture than the sum of its parts: Seven Advanced Composition Rules You Probably Didn’t Know

There are a lot of sayings going around in photography that sound impressive but are meaningless. However, an image larger than the sum of its parts is something we should pay attention to because it is the basis of how our minds perceive the image. Here are seven ways to achieve this.

Learning the rules of photography is important. If we study why a photo looks great, the eye for good composition will help us to create well-composed photos without thinking about it. For example, many new photographers start by learning the rule of thirds. Like riding a bicycle, it becomes natural to frame the shot this way. Next, they may discover leading lines and those lines also become part of their subconscious. They can then investigate the golden ratio and dive into color theory. As they became more and more advanced, so did new compositional techniques become ingrained in their minds. With enough practice, they are also used without a sober thought.

People often say that we should break the rules of photography. Even when we do, however, we often apply other established techniques instead, even if we don’t necessarily know about them.

But have you ever thought why some works work and others don’t? It all has to do with how our brains process the scenes presented to us. Digging deep into this can help us perfect our photography.

As we look at the world around us, our minds organize the objects we see, grouping them in certain ways that allow us to perceive the landscape as a whole. We can also see groups of objects, but not individually, because we will overcome sensory overload.

The closer the objects are together, the more likely we are to group them together. For example, when we stand back and look at a building, we will see the wall, not the specific bricks. Likewise, we observe a tree branch, not individual trees. Move closer and groups become different; we see the whole tree. However, not all of its individual parts are recorded in our minds. If we get closer, each of those smaller features forms their own groups: leaves, twigs, and bark patterns. However, we did not find leaf veins, lichens growing on branches, or insects hiding between the contours of the bark. This type of grouping is called a proximity rule.

Furthermore, the killing of starlings is considered a single organism rather than individual birds. However, the mind sees this collection of birds as a shape in the sky. It is the shape that our brain mainly perceives.

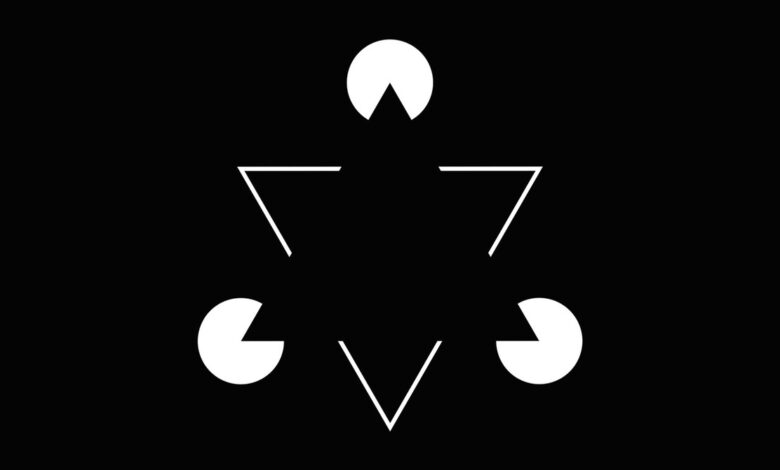

We also view a stone circle as a circle rather than a collection of individual stones. This is because your mind fills the void, creating shapes that don’t really exist. That process that helps us simplify a scene is called the closure rule. In other words, we cannot help but see the overall shape formed by the grouped objects.

Perhaps the most famous demonstration of the closure law is the following diagram. Named after an Italian psychologist who designed its first version, the Kanisza triangle makes the mind believe that a black triangle exists when there are only three circles with sliced pizza slices. out from them. You also assume the existence of a white triangle, when in fact there are three Vs.

In addition, the mind also has the expectation that the grouped items will work together, acting as an object and not individually. This is called the law of common destiny. For example, in the following picture, kayaks are grouped in our minds as one entity and arctic terns are another. We expect both groups to behave independently of the other, but consistently within their own group.

The proximity of individual elements, like bricks in walls, leaves on trees, and flocks of birds, is just one way our minds group objects. But how about when the items are further apart? The mind also groups objects together if they are similar. This can have color, size, shape or form. If some items in the pane look similar, even if they’re not close together, we’ll still group them together if they’re similar in some way. Of course, this is called the law of similarity.

Removing distracting elements and reducing clutter, often works well in photography. This is because the human mind is geared towards simplicity. Well, of course, it’s called the law of simplicity. It’s not just about removing subjects from the frame. The mind creates order in complex shapes and patterns to simplify what we see. Think of constellations. We look up at the sky and see Orion’s form, but that’s only in our mind. In fact, its nearest star, Bellatrix, is only 245 light-years from Earth, while Alnilam is 1342 light-years away. Nothing connects these two stars except a pattern that has been globally recognized since ancient times.

In photography, simplicity can also be achieved by creating balance in an image, pleasing to the human mind. Symmetry is a basic form of balance, and there are many other ways to achieve it, which I will cover in a future post.

The law of good continuity says that the mind will extend shapes and lines beyond their endpoints. In landscape photography, we may have a fallen tree branch in the foreground facing a distant subject, or we may have a series of rocks facing away from the horizon. The viewer’s eyes follow that line, drawing an invisible line between them.

Another thing we photographers often do is try to make the subject stand out from its background. If an image is cluttered with many similar-looking subjects, focus will be lost. We use different tools to make the subject stand out from the background, such as selective lighting, shallow depth of field, and color selection of the subject. This allows the selected subject to be perceived.

Using gesture theory in photography

These seven laws are part of Gestalt theory. Although it derives from some sometimes flawed psychological ideas that originated in Austria and Germany in the early 1900s – observed objects do not reflect themselves in our brains – the theoretical approach Modern theory helps us understand why certain works work and others don’t. We can use these techniques to draw the eye to the parts of the photo that we want the viewer to pay attention to.

Gestalt theory explains that the mind likes simplicity and that is achieved by grouping elements in a scene. We also automatically fill in the missing blanks where there is enough information to do so. Therefore, the whole image is greater than the sum of its parts because the mind makes connections between objects. It also says that the mind moves from seeing individual elements to understanding the whole picture.

By learning and understanding the principles, we can increase or decrease the time it takes for our viewers to make sense of our photos. We can also choose whether we want to follow the standard constraints applied to our photos, or deliberately break these constraints and look for dissonance instead. After all, a lot of photographs are taken for the sake of art, and beautiful artwork almost always challenges established and accepted practices.

This paper has barely touched the surface of Gestalt theory; There are many online resources and books on this topic, and I’m planning to revisit some of those rules in their own articles. It’s widely used in design and psychology, and its tools can be applied to all branches of the arts, so there’s no reason we shouldn’t treat it as a toolkit. Other useful for photography.

It would be great to see some of your pictures in the comments applying one or more of the Gestalt rules and I would really love to hear your thoughts on the subject. Thank you for reading.