Wind Turbines Out West-Part 1 – Watts Up With That?

Kevin Kilty

Background

Wind energy development has exploded in southeastern Wyoming. In just two counties we have now in operation, or permitted to begin construction, some ten wind projects involving 613,000 acres (958 square miles) and offering nameplate rating of 6,300MW. Why has this development accelerated so much lately? I will not delve into the issue of public subsidies at all since these are so well known. Instead I will examine five other factors I can identify.

First, the region undoubtedly has impressive wind energy resources and these installations should, like oil and gas production, follow the resource. However, while average wind speeds in parts of southeast Wyoming are high, the wind displays a great deal of variability on a variety of time scales – exactly the characteristic which makes wind energy problematic.

Second, except for one project which is sited in a region of private residences and businesses there is little local opposition to these projects. Everyone seems aware that these projects will pass the permitting stage easily. There is little statutory guidance. There are no regulations regarding impacts to view shed, for instance, like there is in cities (i.e. limitations on structure height, for instance).

Third, the wind farms are being sited where there are few land owners which is a great aid in organizing leases. In this part of Wyoming property is often owned in very large holdings. Much of it is state or Federal land, especially BLM. One project includes a 50/50 mix of private and BLM. The private land involved here has one private owner of around 250 square miles.

Fourth, there is the perception of coming prosperity. Local engineers expect increasing demand for surveying and civil engineering services as do some construction services such as for porta-potties. There is new tax revenue. What is sold to the county is revenue for facilities upgrades, better wages, and equipment for schools.

Fifth, the most difficult factor to put in a proper perspective is the current popular belief that these so-called renewable energy sources are high-tech and will enhance the environment, in fact possibly save the planet. In one case County Commissioners stated explicitly that their decision to approve was predicated partially on reducing greenhouse gasses.

In Part I of this series I will examine the permitting process itself along with environmental and economic issues; then in Part II we’ll tackle technical issues involving hazards to wildlife and preventing nuisances.

The Permitting Process

The permit applications are enormous documents, 1,700 pages isn’t out of the realm of possibility. One should expect that these put forth the applicant’s best case and so they should be read with an appropriate deal of skepticism because they are, by nature, biased.

Public hearings are scheduled to consider the application. My overall sense is that if one has doubts about renewable energy invading your neighborhood or region, public hearings are not a productive place to voice concerns. By this stage the effort has gained too much momentum for approval. Few people in opposition show up generally and many people who do show up in opposition to these permits present emotional, extreme and poorly substantiated claims.[1] People with more persuasive objections get caught up in the resulting emotion and discounted altogether. Send written comments instead and send them early.

The usual path to approval is to first seek approval from the county commissioners who will rely on the opinion of a planning commission. The planning commission typically has knowledge about construction, but not necessarily industry. The minutes of their meetings makes this clear. However, even with obvious shortcomings, the application is sent to the commissioners with a recommendation to approve.

Local approval now leads to a request for a conditional permit from a state agency such as our Industrial Siting Council (ISC). This council in turn will depend on a recommendation from the Industrial Siting Division of the State Department of Environmental Quality, which in turn gathers opinion from many various state agencies. It is a little like being caught in the infinite regress arm of the Maunchausen trilemma. No one in these agencies is a party to the hearing and so they won’t testify in person.[2] Worse still, their advice lacks independence as the agencies are not immune to politics. One person told me some time ago that there is pressure from above, perhaps only perceived but effective nonetheless, to not push back too hard on wind energy.

After having passed public hearings, the client may have other conditions to meet such as from the FAA concerning lighting or perhaps some level of rigor of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) because Federal property is involved and so forth, but hearings are a major hurdle to clear.

The public hearing process makes a good example of C.P. Snow’s “two cultures” – one encompassing the scientific and engineering disciplines and the other the humanities.[3] While he identified this divergence in academia and the elite, the same conflict appears almost everywhere.

The scientific engineering ethos is about evidence and making logical arguments based on what researchers have concluded often after a great deal of independent review. Its knowledge is constantly under revision. Someone who has self-reported experience without data or other evidence is arguing “ex cathedra”– argument from authority. Science and engineering are not about authority, and in our culture we view such claims suspiciously.

The culture of public hearings, on the other hand, often is about authority. An argument made from published studies by a person not directly involved in the research is actually providing hearsay.[4] The legal/procedural ethos places great emphasis on eye witnesses, and cross-examination. If the earlier researchers whose work I drew upon for my testimony can’t be cross-examined, well, as the hearing examiner stated in response to objections, the council would consider my testimony “for what it’s worth.”

In summary there is little opportunity to criticize work the applicant does despite its obvious biases or mistakes. Work done by agency advisors is well insulated from criticism. There is nothing like regulatory Daubert in the Administrative Procedures Act.[5]

The Environment

Nothing seems more misplaced than the belief, amplified by the wind energy developers themselves, that wind energy is clean and non-polluting. Says one application,

“Wind power is a renewable and non-polluting source of electricity. It is clean energy that produces no emissions, which means it does not contribute to acid rain and snow, global climate change, smog, mercury contamination, water withdrawal, or particulate-related health effects.”

The emphasis is mine. This is only true with a very narrow view of the phrase “produces no emissions”. We all know that the steel towers, concrete foundations, plastic and glass blades, copper wound generators/alternators, uses of rare earth elements, and on and on, contain an enormous amount of embodied energy, almost all of which comes from coal, petroleum or natural gas, and carries a very large burden on the environment as well during operations and decommissioning. I can say no more than I wish this were more widely appreciated.[6] Moreover these projects present local environmental costs to wildlife and they utterly alter natural views. The reality of a large wind farm out west is shown in Figure 2. Wind turbines dominate the scene and produce a major visual focus from as far away as 18 miles depending on lighting. If a person hates red blinking light then they’ll find the night-time view worse.

Testimony about environmental harms and nuisances carry little weight with hearing officers because they defer to in-house advisors and even the applicant. They limit testimony severely and often for good reason.

Economics

Wind energy developers emphasize that they are coming with many economic benefits for a community. These benefits loom larger the more needy the local area. Indeed, as a Vermont wind energy opponent has noted they tend to target the poorest of counties.[7] The recently rejected Fountain wind energy project in Shasta County, California targeted one of California’s poorest counties,[8] and the two counties I focus on here are among the poorest in Wyoming.

In Wyoming, which has the reputation of a non-diverse economy, these developers offer their projects as an opportunity to escape from the boom-and-bust cycles of the commodities businesses. In fact, wind energy development doesn’t look much different in this regard.

They may claim they intend to maximize benefits to the local communities. Such statements clearly represent applicant bias as they conflict with the entire reason and purpose of a free enterprise firm which is to minimize costs, not to maximize benefits to vendors. Someone’s expectations are likely not to be met.

What supports the applicant’s economic analysis is an input/output model of the local and regional economy which might be augmented with a social accounting matrix, an I/O-SAM analysis. An input/output model predicts how spending in one industry affects others, and the SAM portion of the modeling accounts for personal spending. I will instead depend on some experience gained from wind energy projects in Colorado.

Benefits come in two forms; new tax revenue and more vigor to the private economy. The developers stress new tax revenue heavily. It is easier to estimate as there are only three sources to examine; sales/use taxes, ad valorem tax, and wind energy excise tax. Developers will often stress that impact assistance funds are available too. However, these are not a separate revenue source, but rather sales/use taxes that would have gone into the State general fund, but are redirected to the county. It’s just moving money from one pocket to another. I think people misunderstand this. They fail to see that it affects the general fund which bears on future funds available to these counties or other counties. That this is simply redirected money lies at the heart of current controversies over these funds being too generous and not well supervised.[9]

The long versus the short term

One hope about wind energy development is that it will add diversity to the economy and help arrest the boom-bust nature of being dependent on mineral commodities. Let’s look at the short term construction phase of a project–a hypothetical project of about 600MW nameplate capacity–and then the long term O&M phase.

A project of this size will first require materials. At least one-half are manufactured outside the area and represent no local earnings. A substantial fraction of the materials will be cement, aggregates, and water which might be locally sourced. This project will add about $30 million of sales/use taxes to the county over a two year span during which the counties would have collected $204 million anyway. So, there is a temporary 15% jump in local government revenues. In addition, during a two-year construction phase there is a need for perhaps 400 construction (direct) jobs, of which 90% are from out of state. These will go away leaving perhaps 30 permanent jobs. The construction period induces local jobs which occur in retail, insurance, recreation, restaurants and lodging. Modeling estimates of induced jobs are too optimistic for our local area. Experience suggests perhaps one-third as many, but the point is 90% of them go away as the project transitions to an O&M phase. I am not denigrating temporary economic benefits, but they couldn’t look more like a boom-and-bust cycle.

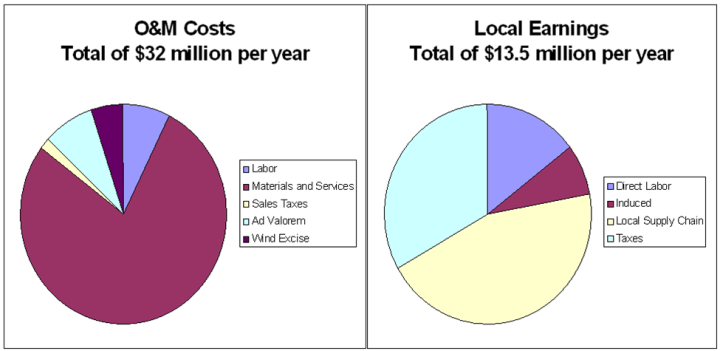

The long term benefits of this project to government agencies will be ad valorem (property) tax, some sales/use tax on supplies and equipment, a minor amount of annual leases on government property, and a wind energy excise tax. To the commercial economy it will be wages paid to personnel, materials and services, sales taxes on consumable or maintenance materials, and leases paid to landowners. There will be some induced job creation as well.

Additional ad valorem taxes amount to about $2.5 million per year. Sales/use taxes are just the county’s ordinary share on the O&M purchases of about $0.4 million per year. State wind energy generation tax revenues are presently set at $1.00 per MWhr but don’t become effective until a wind turbine has been in operation for three full years. This tax is split 40/60 between the State general fund and the county involved.[10]

Figure 3 shows O&M costs of running a facility of this size assuming $45,000 per MW of nameplate rating exclusive of taxes and land leases. Private earnings are much lower than costs because of “leakage” which occurs across the local/regional boundary.[11] Most of the maintenance materials, for example, are not manufactured in the area and will be transported to the site from possibly far away. They may not even be warehoused locally. It’s ironic the extent to which this energy replacement for fossil fuels is going to depend on over-the-road transportation by diesel fuel for operation and maintenance. Earnings are limited by the current structure of the local economy which presents few opportunities to capture the O&M costs. To capture more would take investment by the private economy. I can’t say whether this investment would be wise, or if any local entities would view it so.

Land lease revenues are almost 100% leakage. These are not made to a great many landowners who are likely to spend money locally, but rather are extremely granular payments to people living beyond the local area. One project has only two landowners – the Federal government and someone who lives in a neighboring state. Another project lists five different landowners of which only one lives in the area. Lease payments are not likely to enter the local circulation of money.

Conclusions and suggestions

I will present a more complete list of recommendations at the end of Part II, but at this juncture a few interesting observations are apropos.

First, Figure 3 shows why local governments are so enthusiastic about these projects. A large proportion of local “earnings” pass to government agencies first and then to the public through government services. It looks like how foreign aid works, but we hope it works better.

Second, despite all the silly rhetoric to the contrary these projects offer a boom-and-bust character just like the industrial projects people currently blame for boom-and-bust cycles. People should brace themselves for a boom in years 2023-2025 as numerous projects are constructed, followed by a bust in years 2025-2028 as the induced economy shifts downward to a new equilibrium and before wind energy excise taxes fully arrive.

Third, despite talk of wind energy being an energy source of the future, what it more nearly resembles is ranching of beef cattle which epitomizes an energy source of the past. Ranching beef cattle gathers a low density recurring resource (sunlight and rain) over enormous tracts of land as food energy, while wind energy gathers a low density recurring wind resource over enormous tracts of land as electrical energy.

References:

- McCunney, Robert J. MD, MPH, et al, Wind Turbines and Health, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine: November 2014 – Volume 56 – Issue 11 – p e108-e130 (doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000313). This is a very detailed meta study which wind energy proponents cite approvingly, because it dismisses most claims of health injury. Yet actually it hurts their claims in the instance of noise and sleep disturbance being nuisances.

- These plans are always stamped by a Wyoming PE, who may or may not attend any of the hearings but whom I have never seen called as a witness.

- C.P. Snow, Rede lecture of 1959, and Cambridge press book (1965). While Snow’s thesis was originally about a failing of the British education system versus that of the Germans and Americans, the divide he spotlighted has now diffused more widely through all societies.

- Or at least the attorney from the wind energy applicant warned me he was going to object to my testimony as such. As an example about the divide between the two cultures, in rebuttal to my testimony summarizing all available research about wind energy impacts on pronghorn, a rancher stated that he observes pronghorn take shelter behind turbine towers in hail storms.

- Daubert refers to Federal Rule 702 pertaining to technical/scientific testimony, saying, in effect, that scientific testament has to meet the accepted standards of scientific method.

- One of the applicants in response to local concerns about decommissioning sent out a mailer stating that 90% of wind turbines could be recycled – implying that 90% would be. This is not how things work currently. Repowering old wind plants leads to lots of landfill.

- Jim Motavalli, The NIMBY Threat to Renewable Energy In Vermont, everyone loves clean energy—when it comes from someplace else, Sierra Club Magazine, Sep 20 2021

- Robert Bryce, Here’s The List Of 317 Wind Energy Rejections The Sierra Club Doesn’t Want You To See Forbes Business, Sep 26, 2021

- Recent legislative hearings raised both the issue of lowering the limit to 2.25%, and of auditing how the funds are spent in fact. One legislator suggested the funds could be spent on popcorn machines and no one would know. See “Lawmakers move to limit state aid to communities stressed by large construction”, by Dustin Bleizeffer, Wyofile, January 18, 2022

- Cooper McKim, Proposal To Raise Wind Tax Dies Again In Committee, Wyoming Public Radio, December 18, 2020 It is notable I think that when the legislature made an attempt to increase this tax two $2.00 per MWhr, the industry, through the American Wind Energy Association, lobbied hard against it.

- Jeremy Stefek, et al, Economic Impacts from Wind Energy in Colorado Case Study: Rush Creek Wind Farm, NREL report, 2019. I used many of the estimates and actual numbers from this report to produce Figure 3, while then making adjustments for local tax, population, and private economy structures.