Serious trouble, salt is being created under Antarctic glaciers

The glaciers in Antarctica are are threatened, but not in the way you might think: It’s not the sun shining on them that matters, but the warming ocean water that’s pressing down on them. The part of the glacier that is on land is called the iceberg, and the part that is floating in the ocean is the ice shelf. The exact dividing line between them, where the ice drifts out, is called the ground line. As the world heats up rapidly, that line is falling again. And as a result, Antarctica’s glaciers may be receding much faster than scientists predict.

Think of an ice shelf as a cork that holds the rest of the glacier, that iceberg, from sliding into the ocean. The Florida-sized Thwaites Glacier, for example, is known as the “Doomsday Glacier” for good reason: It’s attached to an offshore reservoir and is holding back ice that could raise water levels Global seas add two feet if it all melts. Last month, scientists reported that the Thwaites ice shelf could crumble in three to five years.

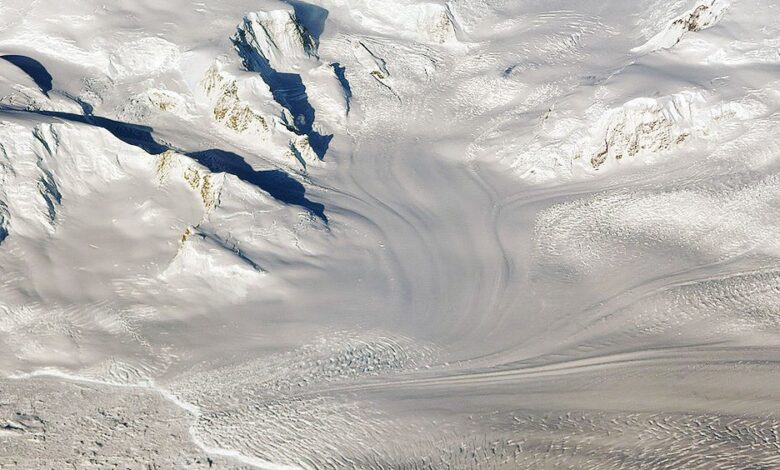

But current models of glacier melt do not explain the phenomenon called tidal pumping. Whenever the tide is high, it pushes the Thwaites ice sheet upward, allowing the relatively warm seawater to flow further upstream below the glacier. That melts along its belly, making the ice more prone to breaking. “That means warm water at the bottom of the glacier can penetrate several kilometers upstream,” said University of Houston physicist Pietro Milillo, who is studying Antarctic glaciers. “And suddenly you start to realize, ‘Wait a minute! Models that actually predict the future state of glaciers do not have these types of phenomena. They basically have a fixed grounding line. ‘”

Last month, Milillo and other scientists reported that tidal pumping is forcing the grounding lines of other West Antarctic glaciers – Pope, Smith and Kohler to retreat rapidly. Using satellites that shoot radar waves at the ice, scientists can detect small changes in altitude along each grounding path. Milillo, lead author of a paper job description in the magazine Natural Geosciences. “So by measuring how much it moves over the top due to the tides, we can actually see the ground line at the bottom of the glacier.”

The colored lines show the rapid retreat of the grounding lines of the glaciers over the past three decades. Thwaites is not envisioned, but it will be on Pope.

Illustration: P. Milillo; E. Rignot; P. Rizzoli; B. Scheuchl; J. Mouginot; JL Bueso-Bello; P. Prats-Iraola; L. DiniThe measurements are terrible. In 2017, Pope’s ground line dropped back more than two miles in just three and a half months. Between 2016 and 2018, Smith recorded one-mile and one-quarter mileage each year, while Kohler retreated three-quarters of a mile. And when that ground line started to recede, it started a series of disasters: The more the glacier’s underside was exposed to seawater, the more it melted. “Once you trigger a sophisticated retreat, they will continue to retreat and retreat, which means they will continue to accelerate,” says Milillo. “Accelerating the glacier works like a gum: Glaciers thin, and by thinning you can speed them up, too, because while not in contact with the riverbed, there is less to it. more resistance to the flow. Means glacier [movement] will accelerate and in turn will pump more ice into the ocean.”

The grounding lines of these neighboring glaciers may even recede to the point where they actually merge. “It will probably take a long time. But if that to be Peter Washam, an oceanographer and climate scientist at Cornell University who studied Thwaites but was not involved in the new study. “The fear with Thwaites is that when you move upstream, it pulls in such a large area of ice that, once you start pulling that fast, you can wrap glaciers around it.”

Think of it like a basin, where several creeks flow into a larger river, but instead of liquid water, it is (slowly) flowing ice. “If you unplug Thwaites, you’re pulling the cork out of the drain,” said Lizzy Clyne, a geophysicist and glaciologist at Lewis and Clark Universities who studies glaciers but was not involved in the new work. hey, say. “Then you allow the previous ice to flow in different directions like, ‘Well, the wall behind me is gone, so now I’m going to fall back to Thwaites.’ And in theory, you could touch more ice. “If Thwaites and the glaciers around it were destroyed, they could rise 10 feet above sea level.