Does beta-amyloid cause Alzheimer’s or is something else to blame? : Shots

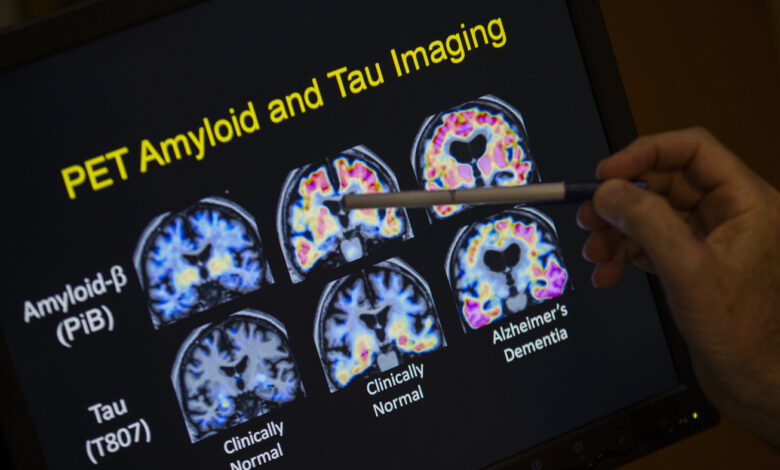

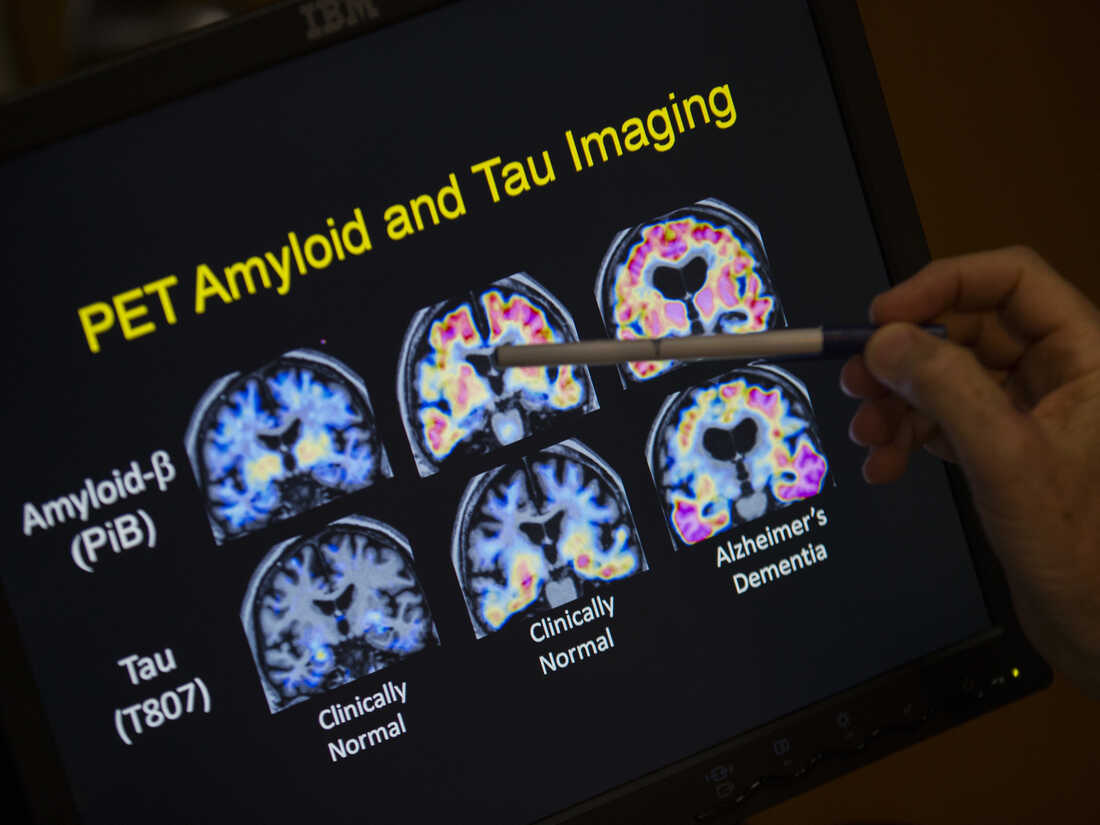

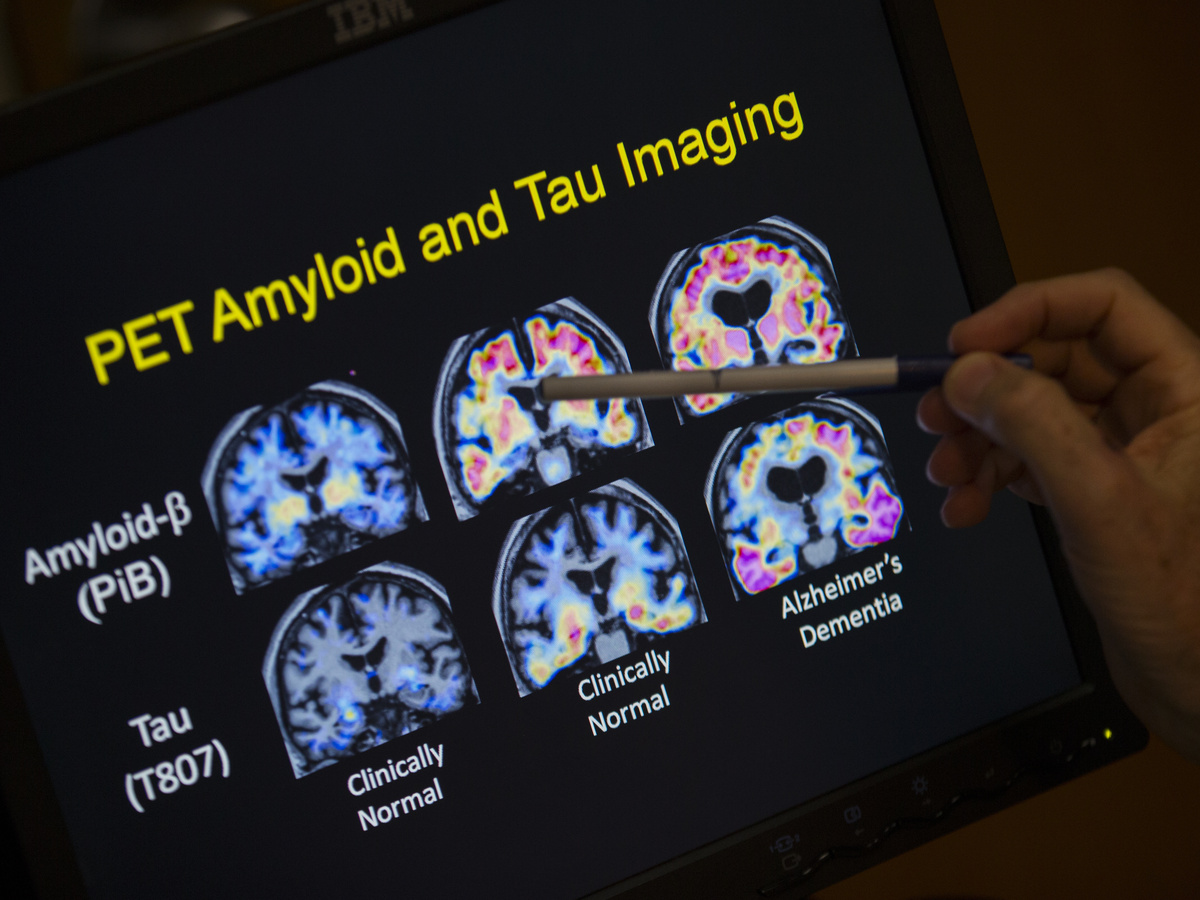

A doctor points to the results of a PET scan as part of an Alzheimer’s disease study. Much work in this area focuses on a substance known as beta-amyloid. A new study could test whether that’s the right goal.

Evan Vucci / AP

hide captions

switch captions

Evan Vucci / AP

A doctor points to the results of a PET scan as part of an Alzheimer’s disease study. Much work in this area focuses on a substance known as beta-amyloid. A new study could test whether that’s the right goal.

Evan Vucci / AP

An idea that has fueled Alzheimer’s research for more than 30 years is drawing near.

Scientists are launching a study to either make or break the hypothesis that Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a sticky substance called beta-amyloid. The study will provide an experimental anti-amyloid drug to 18-year-olds whose genetic mutations often cause Alzheimer’s to appear in their 30s or 40s.

The study comes after several experimental drugs have failure to prevent memory and thinking decline, although they have been successful in removing amyloid from the brains of patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Those failures have eroded support for the idea that amyloid is responsible for a series of events that ultimately lead to the death of brain cells.

“Many of us thought it was the ultimate test of the amyloid hypothesis,” Dr. Randall Batemana professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

New test, called Primary Prevention Trial DIAN-TUis expected to begin enrolling patients later this year.

An explanation with a history

The amyloid hypothesis can be derived from Dr. Alois Alzheimer’sA pathologist who first described the disease that bears his name in 1906.

Alzheimer was working at a psychiatric clinic in Munich, where he had the opportunity to conduct an autopsy on a woman who had died at the age of 50 after suffering memory loss, disorientation and hallucinations. He observed that the woman’s brain had an “abnormal disease of the cortex,” including the “age-related plaques” commonly seen in people much older.

In the 1980s, scientists shows that these plaques are made of beta-amyloid, a substance that exists in many forms in the brain, from single free-floating molecules to the large aggregates that form the sticky plaques reported by Alzheimer’s disease.

Since that discovery, most Alzheimer’s treatment efforts have involved drugs that target different forms of amyloid. And that approach still makes sense, Bateman said.

“We have solid data for 30 years, thousands of studies all saying this is enough to cause Alzheimer’s,” he said.

But doubts about the amyloid hypothesis have grown as the list of failed drugs has grown over the past decade.

For example, Bateman and a team of researchers were unable to prevent Alzheimer’s disease in a study of patients given anti-amyloid drugs. gantenerumab.

“What we found was that it reversed the amyloid plaques in their brains,” Bateman said. “We don’t have evidence for the benefit of mental memory.”

Even so, Bateman and many other scientists say it is too early to abandon the amyloid hypothesis.

“Penicillin, a great breakthrough, failed in the first two clinical trials,” says Bateman. “Fortunately, people didn’t say, well, antibiotic theory is a bad idea and we should give it up.”

Suggestions for benefits

Bateman is encouraged by results from recent studies of anti-amyloid drugs, even those that do not prevent cognitive decline.

Gantenerumab, for example, seems to delay some of the brain changes associated with the death of brain cells, he said.

And the experimental drug lecanemab appeared to slow memory loss and thinking in a study of nearly 1,800 people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study. statement from the drug manufacturer.

Many studies on anti-amyloid drugs may have failed because they were given to people who already had amyloid plaques in their brains. At that point, Bateman said, it may not be possible to stop the process that eventually kills brain cells.

So Bateman is optimistic about the upcoming prevention trial, which will start treatment much sooner.

“My prediction is it will work, and it will work great,” he said. “If we can really stop the arrays from starting and taking off and those downstream changes from taking place, my prediction is that those people will never develop Alzheimer’s disease.”

Prevention research is based on the idea that when amyloid begins to form, it causes a series of changes in the brain. Dr. Eric McDadea professor of neurology at the University of Washington, who will oversee the experiment.

These changes include the appearance of toxic substances tau disturbances within nerve cells, loss of connections between neurons, inflammation and ultimately death of brain cells involved in thinking and memory.

“What we’re trying to do is stop that amyloid from developing in the first place,” says McDade.

However, that kind of prevention would mean starting treatment long before symptoms appear.

“By the time someone has symptoms, we know they may have had amyloid in the brain for one to two decades,” McDade said.

Thus, the four-year study will enroll approximately 160 people from families with Inherited dominant Alzheimer’s disease. This form of dementia is caused by an inherited, rare genetic mutation that causes Alzheimer’s to develop in middle age, usually occurring in a person’s 30s and 40s.

“The earliest they can come is 25 years before we predict they will start to develop symptoms,” says McDade. “For most of these families, that really put them in their 20s when we started this trial.”

Like the previous study that failed, this study will use the anti-amyloid drug gantenerumab.

The short-term goal is to ensure that amyloid plaques do not appear. The researchers will then see if this prevents the appearance of other signs of Alzheimer’s effects on the brain.

One of these markers is the presence of nerve fiber disorder, a toxic version of a protein called tau forms disorganized fibers inside neurons. These internal plexuses disrupt a cell’s ability to transport chemicals and nutrients from one place to another and maintain connections with other cells.

Another sign is brain atrophy, the shrinking of one or more brain regions due to the loss of nerve cells and the connections between them.

“If we stop the amyloid pathology from developing and these other signs continue to grow and unfold, then this would be one of the best ways to say, listen, amyloid really isn’t,” McDade said. is what we should aim for.”