‘Do I still get it?’: What happened to Teofimo Lopez?

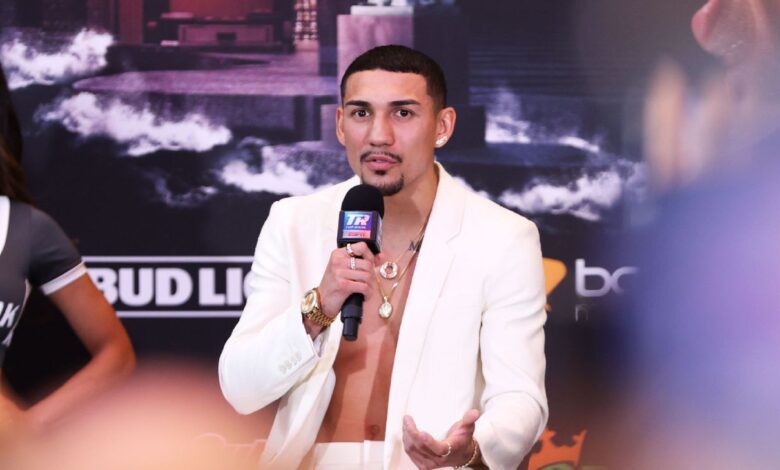

NEW YORK — On the night of February 3, 2018, in the lobby of a Corpus Christi Holiday Inn, I ran into Teofimo Lopez, then celebrating his eighth professional win, with his father. His mother is very happy and loving. He’s 20 years old, still a bit skinny and quite pleased with himself, as he should be, having just beaten a 44-fight veteran even though a very veteran headbutt made him convex and has rows of stitches on the body. his other childish face.

He wears a wine-colored tuxedo with a black scarf over a black shirt. The effect is especially beloved: part Bar Mitzvah boy, part gangster. He lowered his sunglasses so I could photograph the final callus. If Teofimo is eager to be the center of attention, he’s even more eager: a child star just starting to make his way into the world of grown-ups. The day before, during boxer meetings, Lopez told us that his mother no longer had to work as a bartender, that he had moved the family into a six-bedroom, 10,000-foot home. square in Las Vegas. Yes, the child has every right to be proud.

But now, on the eve of his 140-pound title fight with Josh Taylor — a big, badass, highly skilled boxer, with victories over almost every type of boxer available — Lopez has speak he wants to kill Taylor in the ring. And I wonder what happened to the kid I met in Corpus Christi, Texas.

“He’s here,” Lopez said as we sat in New York just days before he won the title. “He’s a kid becoming a man.”

But say you want to kill a man, is that how a man should act?

“There’s nothing wrong with it,” he said. “Will you tell me boxing is not a deadly sport?”

We’re fighting this battle in nine minutes, on camera. Lopez fights what he sees as hypocrisy by fans and media types. He asked if there was any real difference between what he said about wanting to kill Taylor and Taylor’s own angry prediction – that the undefeated, undisputed former champion would have Lopez battered about physically and psychologically to the point that he will never fight again. Lopez continued, trying to reconcile all of his words about murder with his often expressed desire to be a role model and serve God. He doesn’t come up with a coherent answer, though not for lack of effort, as the 25-year-old invokes in various ways about Jesus, Walt Disney, and Kobe Bryant. It was a lively discussion, but not derailed.

Then his father walked in, the camera still running. He was drinking a soft drink, wearing sunglasses and breaking out in a white sweat. You can feel Teofimo’s mood turn gloomy.

“I was outside,” the father explained. “My wife called me, told me ‘Go inside the house and make sure he doesn’t say s—.'”

When we were ready to move on, Teofimo turned and looked me straight in the eye.

“Do you know why I said I would kill this person?” he asks. “It’s because I want to die, servant.”

“What does it mean?” I asked, “Low death?”

“I want to die. At least if I die, I’ll die doing what I love.”

“You want to die?”

“Yes, but only in Mine ring, you know?”

I do not know.

“I want to die in the ring,” he said again. “But like, it’s a little bit of an inside feeling that I want to have.”

“Fear?” I ask.

“No, not afraid. I’m not afraid. No, the only person I’m afraid of…”

“I have to interrupt.” It was his father. “I must.”

“The only person I fear…”

“You have to explain yourself,” said his father, also named Teofimo. “That you’re willing to die in the ring. That’s what you’re trying to say.”

I’ve seen this move before, usually at our boxer meetups. Elder Lopez is trying to protect the son he loves. He is trying to appease his wife. But he is also taking the stage and becoming the center of attention.

His son turned to me. “That’s great,” he said curtly. “Just ask me questions.”

Of course I saved the hardest one for last. A few weeks ago, Teofimo told Punsh Drunk Boxing, “If they want Black boxers, they can keep them.”

He is referring to several rising young stars with whom he is now sharing the spotlight in the steady promotion of Top Rated. Less obvious is his intention. Jealousy? Arrogant? Racism? I asked him to be specific.

“It’s just a bias, part of what I’m seeing in our field,” said the son of Honduran immigrants. “Because it seems like some people are biased towards others… I believe the commentators on ESPN’s point of view are slightly biased towards certain fighters.”

His explanations are everywhere: part opinion, part rationalization, part fantasy. Some are downright libelous, but overall are deeply disappointing. Just two years ago, Lopez was seen as the great, glittering hope of a sport in decline, its most dynamic young boxer, the consensus boxer of the year after his disappointment last year. 2020 against Vasiliy Lomachenko (in fact, a battle that happened only because of his overbearingness). father pushed relentlessly for it).

Now, the more eccentric Teofimo becomes, the more his father tries to restrain him. he shouted. “That’s not recorded!”

“Let’s record this,” Teofimo insisted.

In an instant, the scene went off course.

“Turn off recording!” his father shouted.

“No,” insisted the son, “it’s not on the record… Put this on the record.”

It continued. And more.

“They will destroy us!” said the father.

“Then let it be,” his son said. “What are you scared?”

“We talked about it before we got here.”

“Don’t b—- about it,” the boy said. “And handle it like a man.”

I have real affection for Lopezes and a deep respect for Teofimo, although he has made things infinitely more difficult with what he has to say about his fellow boxers, the perspective death in the ring and our Hall of Fame analysts. To some extent, any reporter or writer is indebted to his source. And the truth is, no one has been more open to me, or more outspoken, than this family.

They told me about the demons and their struggles, their triumph and dysfunction engulfed three generations. It is likely that every family is, to some extent, dysfunctional, but it is that disorder that tends to produce laureates. The Lopezes – mainly fathers and sons – have shown their full dynamism. I watched through a personal and professional lens as Teofimo became a champion, then a four-belt champion. He was married. He has a son. He is now divorced, and by his own account, faces a custody battle. He talks openly about dying by suicide. Along the way, he not only lost his title, but also risked his life in the process, fighting despite an acute condition called pneumomediastinum with air present in the chest and thoracic cavity.

“You almost died,” I reminded him last summer.

“Good,” he said. “Good. I need that… to realize how dark and evil people really are.”

Now, a year later, after our interview turned into a father-son squabble, and after the father finally left the room, Teofimo turned to me again.

“That’s right there, I’ve been dealing with it for a while,” he said. “My family is scared of everything I say. You know how frustrating that is?”

“I think I understand…”

“No, not a clue,” he said. His voice is cold, but you can feel his heat. “You have no clue. You have no idea what I’ve seen, what I’ve been through and what I’m continuing to walk through. None of you.”

“He’s on a razor blade,” someone in the room said after he left. Sure. But so does everyone in his orbit. Teofimo Lopez isn’t just willing to die on his shield; part of him seems to want to. And you always wonder: is it combat hype or a specially coded cry for help? People risk razor blades just to cover him up, that invisible line separating the journalist from the curious.

Lopez’s final game, his eighth at Madison Square Garden, ended with a controversial and disappointing decision over a cunning but light-hearted European opponent, Sandor Martin. As Teofimo now explains it, he battled with a broken left hand, which was surgically repaired a few weeks later. However, what was remembered soon after the decision was announced, when fully aware that the cameras were rolling, he turned to his father and asked:

“Do I still have it?”

It was a remarkable admission from a fighter. But six months later, when he returned to the Garden, the question remained unanswered. Furthermore, there is one more question: What is the definition of “it”? Does it refer to the thread of mutual exploitation that binds Teofimo to his audience? Or is he talking about real boxing?

His career is like a bullet train. You don’t know if he wants to pull the rope and jump down. Or blow them all away. In theory, Taylor should win. He’s more experienced, more natural in stature and although he hasn’t competed for 16 months, he’s more stable in both his personal life and training regimen.

But that’s just logic, usually not in Lopez’s story. Can I also see Teofimo open a power shot, something of a monstrous beauty that changes the game?

Sure.

However, whatever happens on Saturday night, pray that none of the fighter predictions happen. And pray for the kid who always wanted to please, and now lives behind his famous boxer mask. Teofimo can still lose by winning, or even win by losing. But the only real victory will have to be earned entirely by himself. By himself. Overcome yourself.