Annual GWPF lecture: Climate Uncertainty and Risk

by Judith Curry

My talk on Climate Uncertainty and Risk, presented at the Annual GWPF Lecture

Video of the presentation [here]. My ppt slides can be downloaded here [ GWPF uncert & risk (2)].

Josh has prepared a cartoon montage:

Below is a transcript of my remarks:

I am delighted to be here this evening, to talk about my favorite topic – climate uncertainty and risk. To provide some context for climate uncertainty and risk, lets first consider the so-called climate certainties:

- The Earth’s climate is warming

- A warming climate is dangerous

- We’re causing the warming by emitting CO2 from burning fossil fuels

- We need to prevent dangerous climate change by eliminating CO2

These alleged certainties are associated with apocalyptic rhetoric from UN and our national leaders. Here are some of my favorites:

- “The clock is ticking towards climate catastrophe” – Ban-Ki Moon, UN Secretary General

- “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator” – Antonio Guterres, UN Secretary General

- “Climate change is literally an existential threat to our nation and to the world” – Joe Biden, US President.

The UN Paris agreement targets NETZERO emissions by 2050 to keep warming to within 1.5 degrees. Policy makers and others are grappling with a number of issues in addressing the NETZERO challenge. These include the technical, economic & political feasibility, the priority of climate change relative to other problems, and unintended consequences of a rapid transition of our energy systems.

So how did we come to be between a rock and a hard place on the climate issue, where we are allegedly facing an existential threat. And the proposed solutions are both unpopular and infeasible? Well in a few words, we’ve put the policy cart before the scientific horse.

In the 1980’s, the UN Environmental Program was looking for a cause to push forward its agenda of eliminating fossil fuels and anti-Capitalism. With the help of a small number of well-positioned activist climate scientists, a 1988 UN conference in Toronto recommended that the world “reduce CO2 emissions by approximately 20% by the year 2005 as an initial global goal.” The implicit assumption was that the small amount of warming observed over the previous decade was caused by emissions, and that warming was dangerous.

1988 was the year that the UN established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or the IPCC. The first assessment from the IPCC in 1990 concluded that the recent warming was within the magnitude of natural variability. Well, that didn’t hinder the UN. They went ahead with the 1992 Treaty from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change that was signed by 196 countries, to prevent dangerous anthropogenic climate change caused by emissions.

The second IPCC assessment report in 1995 found pretty much the same thing as the first assessment report. However in the meeting with policy makers to write the summary, there was substantial pressure for a stronger finding. They came up with the word ‘discernible’, and then went back and changed the body of the report to be consistent. At that point, the IPCC lost any pretense of being independent or uninfluenced by politics. Apparently ‘discernible’ was sufficient to justify the 1977 Kyoto Protocol.

A number of leading scientists were deeply concerned about the policy-driven science of the IPCC. Pierre Morel, Director of the World Climate Research Programme, had this to say:

“The consideration of climate change has now reached the level where it is the concern of professional foreign-affairs negotiators, and has therefore escaped the bounds of scientific knowledge (and uncertainty).”

William Nordhaus, Nobel Laureate in economics, stated:

“The strategy behind the Kyoto Protocol has no grounding in economics or environmental policy.”

Mixing politics and science is inevitable on issues of high societal relevance, such as climate change. However, there are some really bad ways to do this, and we’re seeing all of these with the climate change issue. Policy makers misuse science by demanding scientific arguments for desired policies, funding a narrow range of projects that support preferred policies, and using science as a vehicle to avoid ‘hot potato’ policy issues. Scientists misuse policy-relevant science by playing power politics with their expertise, conflating expert judgment with evidence, entangling disputed facts with values, and intimidating scientists whose research interferes with their political agendas.

Apart from politicization, arguably the biggest issue is that we have oversimplified both the climate change problem and its solution. The UN has framed climate change as a tame and simple problem, with an obvious solution that is demanded by the science. The precautionary principle has been invoked, in context of speaking consensus to power. However, climate change is better characterized as a wicked problem, with great complexity and uncertainties, and clashing societal values. When viewed as a tame problem, the climate change problem is framed as being caused by excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which can be solved by eliminating fossil fuel emissions. Both the problem and solution are included in a single frame, whereby the science demands this particular solution. This framing dominates the UN negotiations on climate change.

There’s another way to view the climate change problem and its solutions. This framing views climate change as a complex, wicked problem. This framing of the problem also includes natural causes for climate change such as the sun, volcanoes and slow circulations in the ocean. This framing is provisional, acknowledging that our understanding is incomplete and that there may be unknown processes influencing climate change. While the UN’s framing is about controlling the climate, this other framing acknowledges the futility of control, focusing on managing the basic human necessities of energy, water and food. Economic development supports these necessities while reducing our vulnerability to weather and climate extremes.

Wait a minute. Don’t 97% of climate scientists agree on all this? Doesn’t climate science demand that we urgently eliminate fossil fuel emissions? Here is what all scientists actually agree on:

- Surface temperatures have increased since 1880

- Humans are adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere

- Carbon Dioxide and other greenhouse gases have a warming effect on the planet.

However, there’s disagreement and uncertainty about the most consequential issues:

- How much of the recent warming has been caused by humans

- How much the planet will warm in the 21st century

- Whether warming is ‘dangerous’

- And whether urgently eliminating the use of fossil fuels will improve human well being

Nevertheless, we are endlessly fed the trope that 97% of climate scientists agree that warming is dangerous and that science demands urgent reductions in CO2 emissions.

So how did we come to the point where the world’s leaders and much of the global population think that we urgently need to reduce fossil fuel emissions in order to prevent bad weather? Not only have we misjudged the climate risk, but politicians and the media have played on our psychological fears of certain types of risks to amp up the alarm.

Psychologist Paul Slovic describes a suite of psychological characteristics that make risks feel more or less frightening, relative to the actual facts. In each of the risk pairs below, the second risk factor in bold is perceived to be worse than it actually is.

- natural versus manmade risks

- controllable versus uncontrollable risks

- voluntary versus imposed risks

- risks with benefits versus uncompensated risks

- future versus immediate risks

- equitable versus asymmetric distribution of risks.

For example, risks that are common, self-controlled and voluntary, such as driving a car, generate the least public apprehension. On the other hand, risks that are rare and imposed and lack potential upside, like terrorism, invoke the most dread.

Activist communicators emphasize the manmade aspects of climate change, the unfair burden of risks on poor people, and the more immediate risks of severe weather events. The recent occurrence of an infrequent event such as a hurricane or flood elevates perceptions of the risk of low probability events. This then translates into perceptions of overall climate change risk. And so, our perceptions of climate risk are being cleverly manipulated by propagandists.

In spite of the recent apocalyptic rhetoric, the climate “crisis” isn’t what it used to be. Circa 2013 with publication of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, the extreme emissions scenario RCP8.5 was regarded as the business-as-usual emissions scenario, with expected warming of 4 to 5 oC by 2100. Now there is growing acceptance that RCP8.5 is implausible, and the medium emissions scenario is arguably the current business-as-usual scenario according to recent reports issued by the Conference of the Parties since 2021. Only a few years ago, an emissions trajectory that followed the medium emissions with 2 to 3 oC warming was regarded as climate policy success. As limiting warming to 2 degrees seems to be in reach, the goal posts have been moved to reduce the warming target to 1.5 degrees

The most recent Conference of the Parties is working from an expected of warming of 2.4 degrees by 2100, and half of this warming has already occurred. Instead of acknowledging this good news, UN officials continue to amp up the apocalyptic rhetoric. The rationale for continuing to increase the alarm is that the impacts are worse than we thought, specifically with regards to extreme weather. However, for nearly all of these extreme weather events, it’s difficult to identify any role for human-caused climate change in increasing either their intensity or frequency. Even the latest IPCC assessment report acknowledges this. Nevertheless, attributing extreme weather and climate events to global warming is now the primary motivation for the rapid transition away from fossil fuels.

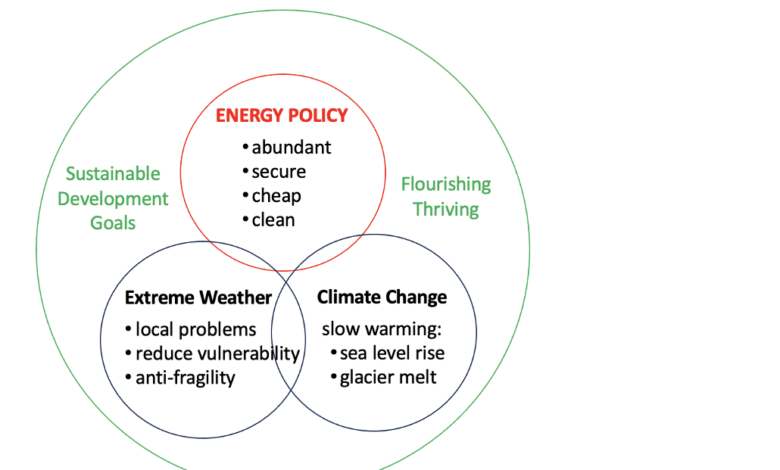

This rationale commits the logical fallacy of conflation. There are two separate risk categories for climate change. The first is the slow creep of global warming, with impacts on sea level rise and glacier melting. The second is extreme weather events and interannual climate variability such as El Nino, which have little if anything to do with global warming.

The urgency of addressing emergency risk is being used to motivate the urgency of reducing the incremental risk from emissions. Reducing emissions will have little to no impact on extreme weather events. Ironically, attempts to reduce emissions are exacerbating energy poverty and unreliability, which increases emergency risk. One would logically think that if warming is less than we thought but impacts are worse, that priorities would shift away from CO2 mitigation and towards adaptation. However, that hasn’t been the case.

Underlying all this is an important moral dilemma that is implicit in climate policy debates. There’s a conflict between possibly preventing future harm from climate change, versus helping currently living humans. The UN policies are targeted at possibly preventing future harm. However, the UN climate policies are hampering the UN Sustainable Development Goals that focus on currently living humans.

In 2015, the world’s nations agreed on a set of 17 interlinked Sustainable Development Goals to support future global development. These goals include, in ranked order:

- No poverty

- No hunger

- Affordable and clean energy

- And development of Industry, innovation & infrastructure

- Climate action

Why should one element of Goal 13, related to net-zero emissions, trump these higher priority goals? International funds for development are being redirected away from reducing poverty, and towards reducing carbon emissions. This redirection of funds is exacerbating the harms of weather hazards and climate change for the world’s poor. Efforts to restrict the production of oil and gas is hampering the #1 goal of poverty reduction in Africa, and is restricting Africa’s efforts to develop and utilize its own oil and gas resources. The #2 goal of no hunger is being worsened by climate mitigation efforts, including restrictions on livestock and fertilizer. Industry and infrastructure require steel and cement, which are currently produced by fossil fuels.

Neglecting these sustainability objectives in favor of rapidly reducing CO2 emissions is slowing down or even countering progress on the most important Sustainable Development Goals. This statement from a recent UN Progress Report particularly struck me: “Shockingly, the world is back at hunger levels not seen since 2005, and food prices remain higher in more countries than in the period 2015–2019.”

Leading risk scientists and philosophers, who don’t have a particular dog in the climate fight, have expressed their concerns about how all this has evolved and where its headed. Norwegian risk scientist Terje Aven has this to say:

“The current thinking and approaches have been shown to lack scientific rigor, the consequence being that climate change risk and uncertainties are poorly presented. The climate change field needs to strengthen its risk science basis, to improve the current situation.”

Political philosopher Thomas Wells states:

“The global climate change debate has gone badly wrong. Many mainstream environmentalists are arguing for the wrong actions and for the wrong reasons. And so long as they continue to do so, they put all our futures in jeopardy.”

The diagram below summarizes the UN view of climate risk. I call this the “climate is everything” view, based on a recent cover story in Time magazine. Under this perspective, climate change is a big umbrella that subsumes extreme weather and energy policy, and causes many of the world’s problems. The most recent problem that I spotted is that climate change is harming Indonesian trans sex workers. Go figure. The “climate is everything” perspective is reinforced by a broader view, espoused by the UN and others, that the environment is fragile, there are too many people, capitalism is bad, and therefore we need global control of all these issues.

The following figure provides a different view, that is more consistent with a human centric perspective and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Further, this view is consistent with human flourishing and thriving, to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Most importantly, this view regards climate change, extreme weather, and energy policy as three different issues, albeit with a small overlap. Energy Policy is regarded as primary, since abundant energy is needed to manage whatever challenges from climate change and extreme weather that we may face in the future. And to spur human development – energy is the motive power that pushes the frontier of human knowledge and advancement.

The following figure provides a different view, that is more consistent with a human centric perspective and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Further, this view is consistent with human flourishing and thriving, to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Most importantly, this view regards climate change, extreme weather, and energy policy as three different issues, albeit with a small overlap. Energy Policy is regarded as primary, since abundant energy is needed to manage whatever challenges from climate change and extreme weather that we may face in the future. And to spur human development – energy is the motive power that pushes the frontier of human knowledge and advancement.

Once we separate the incremental risk of warming from the emergency risks associated with extreme weather, the problems and their solutions become more tractable. My book Climate Uncertainty and Risk argues for a reset of climate and energy policy, that is consistent with the human centric perspective. First, we need to face some inconvenient truths about climate risk.

Risks from climate change and extreme weather are fundamentally local. The risks are entwined with natural climate variability, land use, & societal vulnerabilities. Blaming weather catastrophes on fossil fuel emissions deflects from the real causes of our vulnerabilities, which includes poor risk management & bad governance. And finally, many people fear a future without cheap, abundant fuel and continued economic expansion, far more than they fear climate change.

There are also inconvenient truths about the UN climate & energy policies. The urgency of meeting NETZERO targets is causing us to make bad choices about future energy systems.

Wind & solar power is impairing grid reliability and increasing the cost of electricity. If we somehow reach net zero by 2050, we will notice little if any change in the climate before 2100, relative to natural climate variability. We can’t control the climate or extreme weather events by eliminating emissions.

Given that the UN has mischaracterized climate risk, it will come as no surprise that we are mismanaging climate risk. The left-hand side of the diagram summarizes elements of the UN approach to climate risk management. The right-hand side of the diagram is a perspective that I describe in my book, informed by modern risk science. This includes elements of what has been called Climate Pragmatism and Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty

- On the left, we have a tame problem, while on the right we have a wicked problem

- On the left, we have global problem and a global solution, while on the right, problems and solutions are regional

- The left hand side seeks to control the problem, while the right hand side seeks to understand the problem and manage its impacts

- On the left, the focus is agreeing on the problem, while right focuses on agreeing on no-regrets solutions

- On the left, there is a focus on consensus and speaking consensus to power, while the right hand side acknowledges uncertainties and disagreements

- On the left we have the precautionary principle, while on the right we have robust decision making

- The UN strategy imposes targets and deadlines, whereas the strategy on the right uses adaptive management that is flexible, and incorporates new understandings as they become available.

In terms of politics, the UN strategy is deeply polarizing, whereas the strategy on the right seeks to secure the common interest of communities.

Once you separate energy policy from climate policy, the way forward for energy policy is fairly straightforward. A more pragmatic approach to dealing with climate change drops the timelines and emissions targets, in favor of accelerating energy innovation. The goal is abundant, secure, reliable, cheap & clean energy.

The energy transition can be facilitated by: accepting that the world will continue to need & desire much more energy; developing a range of options for energy technologies; removing the restrictions of near-term targets for CO2 emissions; and using the next 2-3 decades as a learning period with intelligent trial & error. All technologies should be evaluated holistically for abundance, reliability, lifecycle costs and environmental impacts, land and resource use. Without focusing on CO2 emissions, odds are that this strategy will lead to cleaner energy by the end of the 21st century than by urgently attempting to replace fossil fuels with wind and solar power.

The wickedness of the climate problem is related to the duality of science and politics in the face of an exceedingly complex problem. There are two common but inappropriate ways of mixing science and politics. The first is scientizing policy, which deals with intractable political conflict by transforming the political issues into scientific ones. The problem with this is that science is not designed to answer questions about how the world ought to be, which is the domain of politics. The second is politicization of science, whereby scientific research is influenced or manipulated in support of a political agenda. We have seen both of these inappropriate ways of mixing science and politics in dealing with climate change.

There’s a third way, which is known as “wicked science.” Wicked science is tailored to the dual scientific and political natures of wicked societal problems. Wicked science uses approaches from complexity science and systems thinking in a context that engages with decision makers and other stakeholders. Wicked science requires a transdisciplinary approach that treats uncertainty as of paramount importance. Effective use of wicked science requires that policy makers acknowledge that control is limited and the future is unknown. Effective politics provides room for dissent and disagreement about policy options, and includes a broad range of stakeholders.

My book Climate Uncertainty and Risk provides a framework for rethinking the climate change problem, the risks we are facing, and how we can respond. This book encompasses my own philosophy for navigating the wicked problem of climate change. As such, this book provides a single slice through the wicked terrain. By acknowledging uncertainties in the context of better risk management and decision-making frameworks, and with abundant energy, there’s a broad path forward for humanity to thrive in the 21st century.

Thank you

JC remarks

This was a very enjoyable evening, and I very much appreciate the invitation from GWPF