A ‘mass migration’ of polar bears from Alaska to Russia has taken place, local residents claim – Is that so?

Dr. Susan Crockford

An article in a UK newspaper yesterday contained claims by locals that the polar bears that once lived around Utqiagvik (formerly known as Barrow) in western Alaska, are ‘on the move’ to Russia’ (i.e. the Chukchi Sea) in a ‘mass exodus’. ‘. It’s certainly possible but if so, it wouldn’t surprise anyone and be good news for polar bears.

If the allegation is substantiated by scientific evidence, polar bears will not be to push out of Alaska due to lack of summer sea ice (ie ‘forced to migrate’) but more correct drag into the Chukchi Sea because the abundant food source did not exist when the summer ice cover expanded. That’s a big difference, and it speaks to the benefits of less sea ice in the summer that no one wants to discuss.

Moreover, temporarily moving to the most suitable conditions is what polar bears have always done: it is not a new phenomenon, it is a prominent feature of their biology (Crockford 2019).

The article in question appeared yesterday in the UK Daily telegram (January 1, 2020), “Polar bears are forced to migrate from the US to Russia because of climate change”. Oddly, the piece produced a record high temperature on Gifting Day 2021 in Kodiak (located in the Gulf of Alaska, nowhere near Beaufort Sea and in the south of polar bear territory) there is no summer sea ice much further north [my bold]:

After two days of driving through the thick snow of the North Pole, we saw no sign of a polar bear. The beasts, the locals warn, are move to Russia.

“It’s not always the case,” said Herman Ahsoak, a whaling captain from Utqiagvik, Alaska, who works as a guide.

“In the late 1990s, there were 127 people here. I have never seen so many in my life. We have a dedicated patrol team to watch and protect the town.

“But when the sea ice really started to recede, we didn’t see them as often anymore. I’m sure there’s still a healthy population, but they’ve mostly moved from here.”

In this part of the US, where the average annual temperature has increased by 4.8°C over the past 50 years, one of the most visible signs of global warming is The mass exodus of polar bears.

Global warming has caused sea ice to melt, depriving bears of homes and hunting grounds…

The problem was immediate: On Gifting Day, the temperature spiked to a record 19.4 degrees Celsius on Kodiak Island — the highest December reading ever recorded in Alaska.

Polar bears, with 42 razor-sharp teeth, paws the size of dinner plates, and 4 inches of fat beneath their black skin and white fur, are some of the most resilient mammals on the planet. But scientists believe climate change has drive them away.

Far to the west, on Russia’s Wrangel island in the neighboring Chukchi Sea, the population has grown dramatically, with scientists tallying a record 747 bears in 2020, up from 589 in 2017. .

The total number of polar bears in the Chukchi Sea has increased to 3,000 and they are described as “in better condition, larger and appear to have a higher reproductive rate than bears living in the southern Beaufort Sea”, Dr. Karyn Rode, from the Alaska Science Center.

Dr Robert Suydam, senior wildlife biologist with North Slope Borough, in Utqiagvik, said: “What is portrayed in the press and what is promoted by environmental groups makes a lot of difference. stress because it is not an exact picture.

“They regularly estimate that populations in the Beaufort Sea have declined significantly, but they do not take into account the number of bears that have migrated to other areas.

“Without a doubt, polar bears are struggling and will grapple with the changing ice. They have to adapt and rightly so. But unfortunately, some groups that are advertising that the bears are struggling have not given the bears enough credit for how they can adjust to the changing environment. “

…

Because the Chukchi waters off the coast of Russia are so rich with food, polar bears seem to need less time on the ice.

Eric Regehr, a former biologist in the US, said: ‘The bears can tolerate shorter periods of time on sea ice each year because when they’re on the ice, there’s a lot of seals going around to compensate. compensate those losses”. Fish and Wildlife Service currently works at the University of Washington.

The problem here is the ‘mass migration’ of bears.

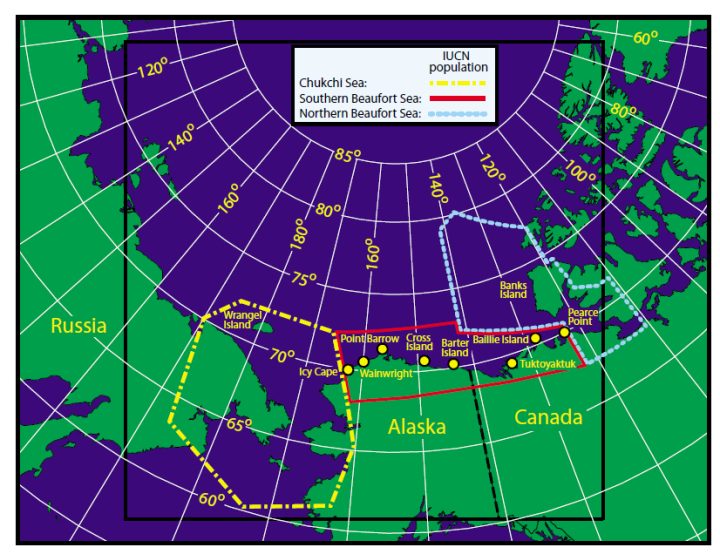

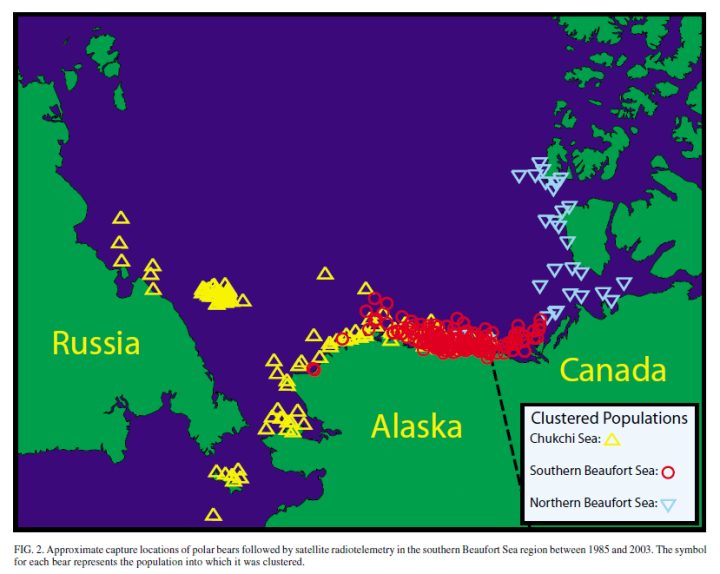

In fact, it was known for decades that most bears that visit Utqiagvik actually belong to the Chukchi Sea subpopulation: almost all of these visitors are invariably Russian, not Alaskan bears (see below from Amstrup et al. 2005; see also Amstrup and associates 2001).

In fact, bear movement in and out of Southern Beaufort at both ends has confused attempts to get a accurate population size estimate (AC SWG 2018; Atwood et al 2020; B magnehin et al 2015; Conn et al 2021; Rehehr et al 2018).

Furthermore, very few South Beaufort or Chukchi sea bears have ever reached land: these are the subpopulations where most bear species stay on sea ice year-round (Crockford 2018, 2019; Rode et al. 2015).

And while these people blame the lack of sea ice in South Beaufort for the bears running away, author of the message omits to explicitly state a clear alternative explanation (although he alludes to it): the abundance of food in the Chukchi Sea in recent years is due to larger main yield in the longer ice-free seasons have made ice over Russia’s seas more attractive place to live for polar bears (Frey et al. 2021; Rode et al. 2014, 2018).

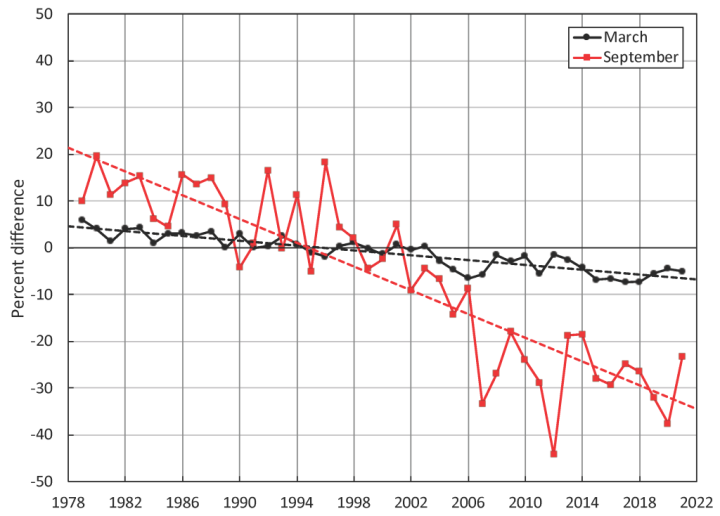

It’s a handy way to present one of the great benefits of Arctic summer sea ice reduction, which causes ‘climate change’ (Crockford 2021). Get used to it: this is something we will likely see more of over the next few years as summer sea ice is predicted to ‘decline’ still stalled (see chart below from Meier et al. 2021).

If it is true that Chukchi Sea polar bears now rarely visit the area around Point Barrow because the bears have moved to Russia (by the way, this is not mentioned by biologists in scientific papers as an excuse). explain to The apparent decline of polar bears in South Beaufort or a clear increase in the number of the Chukchi . Sea), this resistance to changing conditions would be very similar to the situation in the Barents Sea on the other side of the North Pole.

Like me discussed before (with reference), many pregnant polar bears who gave birth in the Svalbard Islands (Norway administered) have largely moved eastward to make their nests on sea ice or islands around Franz Josef Land in Russia. However, those who remained loyal to Norwegian waters had no difficulty, but is thriving (Aars et al. 2017).

Quite simply, this flexibility in responding to changing conditions in the Arctic has allowed the polar bear to be an evolutionary successful species and not a symptom of climate change.

Presenter

Aars, J., Marques, TA, Lone, K., Anderson, M., Wiig, Ø., Fløystad, IMB, Hagen, SB and Buckland, ST 2017. Number and distribution of polar bears in the western Barents Sea. Polar research 36: 1. 1374125. doi:10.1080 / 17518369.2017.1374125

AC SWG 2018. Estimated population demographics of Chukchi-Alaska polar bears. Eric Regehr, Scientific Working Group (SWG. Proceedings of the 10th meeting of the Russian-American Commission on Polar Bears, July 27-28, 2018), pp. 5. Published July 30, 2018. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. https://www.fws.gov/alaska/fisaries/mmm/polarbear/bilateral.htm pdf here.

Amstrup, SC, McDonald, TL and Stirling, I. 2001. Polar Bears in the Beaufort Sea: A 30-Year Recapture Case History. Journal of Agricultural, Biological and Environmental Statistics 6:221-234. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1198/108571101750524562

Amstrup, SC, Durner, GM, Stirling, I. and McDonald, TL 2005. Harvest distribution among polar bear herds in the Beaufort Sea. North Pole 58:247-259. http://arctic.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/426

Pdf here.

Atwood, TC, Bquidhin, JF, Patil, VP, Durner, GM, Douglas, DC and Simac, KS, 2020. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s analysis of cub abundance and annual number of nests of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in the southern Beaufort Sea, Alaska: An open file report of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. United States Geological Survey observer 2020-1087. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20201087. pdf here.

B magnethin, JF, McDonald, TL, Stirling, I., Derocher, AE, Richardson, ES, Rehehr, EV, et al. 2015. Polar bear population dynamics south of the Beaufort Sea during sea ice decline. Eco application 25: 634–651.

Conn, PB, Chernook, VI, Moreland, EE, Trukhanova, IS, Regehr, EV, Vasiliev, AN, Wilson, RR, Belikov, SE and Boveng, PL 2021. Aerial survey estimates of polar bears and their tracks in the Chukchi Sea. PLoS ONE 16 (5): e0251130. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251130 OPEN VIDEO ACCESS: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251130.s003

Crockford, SJ 2018. Polar Bear Report 2017. Report of the Global Warming Policy Organization #29. London. pdf here.

Crockford, SJ 2019. The polar bear disaster has never happened. Global Warming Policy Fund, London. Available in paperback and eBooks formats. Crockford, SJ 2020. Polar Bear Report 2019. Global Warming Policy Foundation Report 39, London. pdf here.

Crockford, SJ in 2021. Polar Bear Status Report 2020. Global Warming Policy Foundation 48, London. pdf here.

Frey, KE, Comiso, JC, Cooper, LW, Grebmeier, JM and Stock, LV 2021. Primary productivity of the Arctic Ocean: response of marine algae to climate warming and sea ice depletion. NOAA Arctic Report Card 2021, DOI: 10.25923/kxhb-dw16

Meier, WN et al. Year 2021. Sea ice. NOAA Arctic Report Card 2021, DOI: 10.25923/y2wd-fn85

Regehr, EV, Hostetter, NJ, Wilson, RR, Rode, KD, St. Martin, M., Converse, SJ 2018. Population aggregation modeling provides the first empirical estimates of the survival and abundance of polar bears in the Chukchi Sea. Scientific reports 8 (1) DOI: 10.1038 / s41598-018-34824-7 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-34824-7

Rode, KD, Regehr, EV, Douglas, D., Durner, G., Derocher, AE, Thiemann, GW and Budge, S. 2014. Differences in the response of Arctic top predators to habitat loss: foraging and reproductive ecology of two polar bear populations. Global change biology 20 (1):76-88. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12339/abstract

Rode, KD, RR Wilson, DC Douglas, V. Muhlenbruch, TC Atwood, EV Regehr, ES Richardson, NW Pilfold, AE Derocher, GM Durner, I. Stirling, SC Amstrup, MS Martin, AM Pagano and K. Simac. 2018. Spring fasting behavior in cetaceans provides an indicator of ecosystem productivity. Global change biology http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.13933/full

Rode, KD, Wilson, RR, Regehr, EV, St. Martin, M., Douglas, DC & Olson, J. 2015. Land use enhancement of Chukchi sea polar bears associated with changing sea ice conditions. PLoS one 10 e0142213.