Police departments are using money to address staffing shortages: NPR

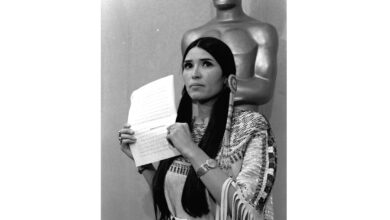

Minneapolis Police Chief Brian O’Hara speaks to the press following a multiple shooting in the city on February 27. O’Hara said the department’s staffing is down 40% compared to 2020.

Alex Kormann/Star Tribune via Getty Images

hide caption

convert caption

Alex Kormann/Star Tribune via Getty Images

When Minneapolis Police Chief Brian O’Hara took over the department in 2022, he said it felt like walking into a funeral home.

“People weren’t even talking to each other,” he said. “A lot of the members were openly telling me, ‘Yeah, if someone asked me, they were thinking about becoming a cop, I told them, no way, don’t come here. Everybody hates us. Everybody’s leaving. Go anywhere but Minneapolis.’”

After all, this is the police force where an officer killed George Floyd. O’Hara said that has taken a toll. He estimates the department is now 40% smaller than it was in 2020.

Across the United States since 2020, police forces in major cities have shrunk. In response, many have raised police pay. But many say it takes more than money to attract people to police work and keep them there.

How many police is enough?

According to the Police Executive Research Forum, or PERF, the number of officers employed by large agencies is about 5% lower compared to four years ago.

In Minneapolis, O’Hara said residents are suffering because there are fewer investigators and fewer police officers on the streets.

“That means response times are much longer for certain things,” he said. “It doesn’t mean we forget about cases, but it does mean we prioritize.”

He said police have less time to take attendance and have less direct contact with community members; they now rely more on single-officer vehicles and are concerned that calling for backup may take longer than before.

Typically, city officials calculate the number of officers needed to consider a department adequately staffed based on a variety of factors including population levels, crime trends and budget allocations.

But there is no magic number, and The evidence is mixed. on whether more police — or more money spent on policing — predicts crime rates, researchers say.

Ben Grunwald, a law professor at Duke University, said there is not yet enough information to say exactly what the best number of police officers really is.

“If you talk to police chiefs and law enforcement experts, they will tell you that we need more police because police help reduce violent crime and solve other problems in the community,” Grunwald said. “On the other hand, you can talk to activists, and they will tell you, ‘No, we don’t need more police. What we need is fewer police because police cause a lot of social harm to the community.’”

‘Departments have had to try to create momentum.’

Chuck Wexler, executive director of PERF, said large agencies struggling to recruit and retain police officers is “a sign of the times.”

“The challenge with policing in the United States today is that you have more resignations and retirements and fewer people wanting to become police officers,” he said. “So police departments have had to try to create incentives.”

In at least 20 major US cities, money is the main driver. Thousands of police officers across the country are set to receive big pay raises starting in 2023.

New student in Austin received a $15,000 signing bonus. In Washington, DC, The recruiting bonus is $25,000..

In May, the Seattle City Council approved 23% increase into starting salaries for public officials. In Kansas City, the 2024-25 budget including a 30% increase in police salary.

Earlier this month, the Minneapolis City Council approved a Increase 22% in the next three years For officers, a pay raise would cost the city plus $9 million.

Minneapolis critics are angry about police pay raises, as the police department has cost the city tens of millions of dollars. compensation for police misconduct. That’s exactly why they need higher wages, O’Hara said.

“If we want quality police, we have to pay quality wages. It’s just a very difficult job and no one cares about it,” O’Hara said. “I don’t think wages are the only thing, but they are a necessary component to turning this around.”

Jill Snider, a retired New York City police officer, agrees.

“We choose to be law enforcement. People choose to be teachers, people choose to be nurses. You know what you’re getting into when you go into it. But then you’re not always happy with the pay when you get it,” said Snider, who is also policy director at the R Street Institute, a research group that promotes limited government.

‘It would take a lot of money to keep me here.’

But just as there is no set number for how many police officers a city should have, the evidence that higher salaries cause more people to become police officers and stay in the profession is mixed.

“It’s not all about money. It’s about quality of life,” Wexler said.

When the Los Angeles City Council voted to raise starting police salaries by 13 percent last year, the city’s police department reported an increase in applications.

ONE Research 2024 It also found that higher salaries made some college students more open to applying for jobs. But the report noted that nearly half of the students surveyed said there was “no chance” they would apply, including many who were majoring in criminal justice.

Other research from this year focuses on burnout and psychological distress as the main reasons police officers leave the profession. Compared to the general population, police are more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorderThey are also more likely to die by suicide.

“Honestly, a lot of times it’s not so much about the money. It’s more about the frustration of the job,” said Colin Whittington, a former officer in northern Virginia.

Whittington, who leaves the force in 2022 after seven years on the job, said he felt unfairly treated because of the actions of other officers.

“You get cursed at, or sent nasty text messages, or left notes in patrol cars about an incident that happened in multiple states with cops I’ve never met, and lumped in with their actions, even though I always hold myself to really high standards,” he said.

Whittington now offers career counseling and has also written a book to help police and other first responders considering a career change away from law enforcement.

Matt Rivers, a former Urbana, Ill., police officer, retired from police work in 2017 after nine years. For him, it was the stress of work that was seeping into his life at home.

“I just remember getting angry at my kids for something really small, like they dropped a spoon in the kitchen or something. And I remember thinking, ‘This is not like me,’” he said. “It would cost a lot of money for me to stay.”

‘The purpose will go beyond money.’

There are some cities that are bucking this trend. In fact, according to PERF data, smaller departments have rebounded from the decline and have more officers now than in 2020.

In Bloomington, Minn., a suburb of nearly 90,000 people a few miles south of Minneapolis, the police department is overstaffed.

“Bloomington was definitely my number one choice. I’m from here. I played sports here. I care about this community,” said Devon Barnum, 23, who has been on the job less than a year.

On a recent afternoon patrol, he responded to call after call: A heated argument between a mother and son. A welfare check on a woman who didn’t show up for work. A traffic stop. A call to protect an apartment building.

“Every day is a challenge,” Barnum said. “Obviously I would say it’s a very stressful job, right? The things you see in this job… the average person doesn’t see them.”

He added that money could not convince him to leave and move to another police department.

“I’m not going anywhere. We have the support of the community. Our leader is fantastic,” he said. “You don’t get into this business for the money.”

To be clear, Bloomington has been raising police pay — about 3 percent a year for the past few years. The city’s police chief, Booker Hodges, said he has no plans to go beyond that.

“Fundamentally, I don’t believe that paying people these incentives is going to work,” he said. “I want people to be here for a purpose, because purpose transcends money… Purpose keeps people going. Purpose gets you through those tough times.”

Hodges was the city’s first black police chief and a former president of the Minneapolis NAACP. He understood that not everyone liked the police. Instead, he sought mutual respect, both for the community and for the officers.

That creates a positive work environment, he said. Otherwise, he said, staff shortages, which lead to more overtime, become a vicious cycle.

“If you’re working 16 hours a day, one: How sane are you going to be, right? Two: How much quality time do you have to recharge and spend with your family, right? Are you going to be your best if you’re working that much? And the answer is no,” he said.

Hodges says you want the police Go out to be healthy and happy, not just for money.