Humans have broken the basic law of the ocean

On November 19, 1969, CCS Hudson slide through the frigid waters of Halifax Harbor in Nova Scotia and out into the open sea. The research ship is on the job many marine scientists on board considered the last great ocean voyage unexplored: the first complete circumnavigation of the Americas. The ship headed to Rio de Janeiro, where it will pick up more scientists before passing through Cape Horn — the southernmost point in the Americas — and then heading north across the Pacific Ocean to pass through the icy Northern Passage. back to Halifax Harbour.

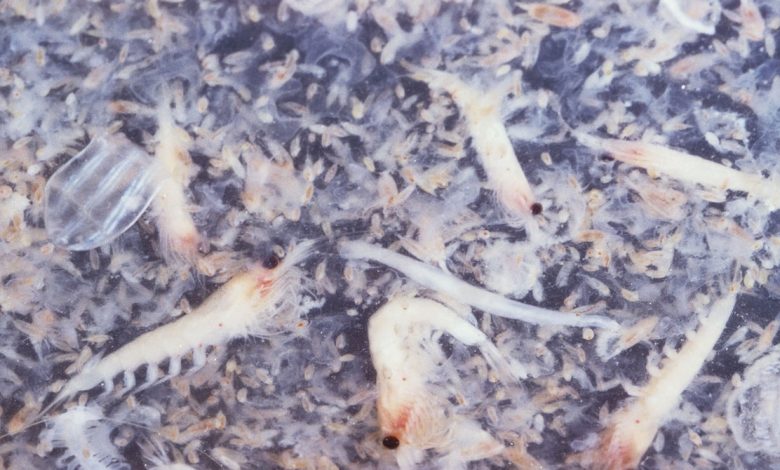

On the road, Hudson will stop regularly so its scientists can collect samples and take measurements. One of those scientists, Ray Sheldon, was on board Hudson in Valparaiso, Chile. A marine ecologist at Canada’s Bedford Institution of Oceanography, Sheldon was intrigued by the microscopic plankton that seem to be ubiquitous in the ocean: These tiny creatures have spread far and wide. star? To find out, Sheldon and his colleagues pulled buckets of seawater up to Hudsonlab and used a plankton counter to sum up the size and number of organisms they found.

Life in the ocean, they found out, which follows a simple mathematical rule: An organism’s abundance is closely related to its body size. In other words, the smaller the creatures, the more of them you’ll find in the ocean. For example, krill are a billion times smaller than tuna, but they are also a billion times more abundant.

What’s more surprising is how precisely this rule seems to work out. When Sheldon and his colleagues sorted their plankton samples in order of magnitude, they found that each size frame contained exactly the same mass of organisms. In a bucket of seawater, one-third of the plankton mass would be between 1 and 10 micrometers, another third would be between 10 and 100 micrometers, and the final third would be between 100 micrometers to 1 millimeter. Each time they move up a group of size, the number of individuals in that group decreases by a factor of 10. The total mass remains the same, while the size of the population changes.

Sheldon thinks this rule could govern all life in the ocean, from the smallest bacteria to the largest whales. This hunch turned out to be true. The Sheldon spectrum, as it is known, has been observed in plankton, fish and also in freshwater ecosystems. (In fact, one The Russian zoologist observed similar pattern in the soil three decades before Sheldon, but his discovery went largely unnoticed). “It’s been suggested that no size is better than any other,” said Eric Galbraith, professor of earth and planetary sciences at McGill University in Montreal. “Everyone has the same cell size. And basically, for a cell, it doesn’t matter what your body size is, you just tend to do the same thing. “