Democracy is demanding too much of its data

Abraham Lincoln was expressed wanted, in times of civil war, to preserve a government “of the people, by the people, for the people.” What he doesn’t say is that such government is also always concerned with data, by data, and sometimes with data. Democratic governance has been essentially data-driven for a very long time. The right of representation in the United States is subject to a constitutional requirement, established at its founding, to “de facto census” the population every 10 years: a census designed to ensure that the population are represented exactly, in their correct place and corresponding to relative numbers.

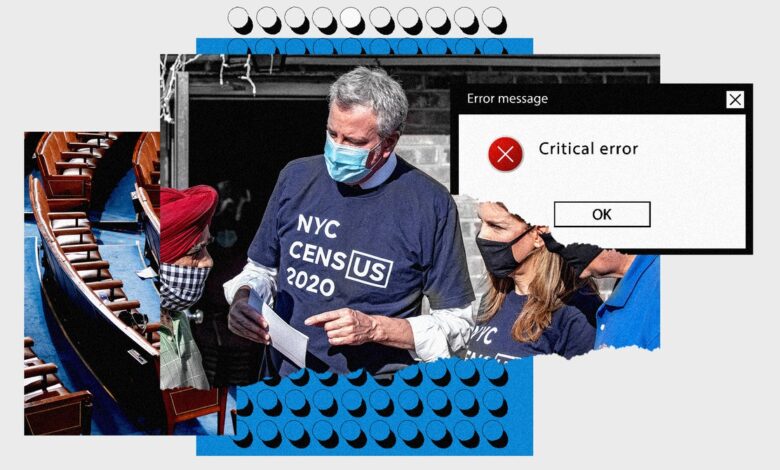

The national census has always been a big task, but the most recent actual census has faced unprecedented challenges. The 2020 census must first overcome the Trump administration’s ill-advised attempt to add a citizenship question. It then spent half a year in the stress field counting every person during a pandemic that has made knocking on strangers’ doors especially difficult. A series of hurricanes and wildfires added to the challenge. And yet, at the end of April 2021, professional officers of the United States Census Bureau fulfilled their constitutional duty and revealed the state’s total population, converting these people into a percentage of the population. number of 435 seats in the United States House of Representatives and a corresponding number of votes in the Electoral College. (The allocation happens automatically according to an algorithm, called “equal-proportion” or “Huntington-Hill”, which is mandated by law.) Now, just last monthwe know that some of those numbers are, most likely, wrong.

The Census Bureau’s Post-Registration Survey (PES) went back to the field, re-interviewing a sample of people from around the country, then comparing the new, more in-depth survey with the results. of the census. Analyzing this comparison, the estimate now that the 2020 census exceeds eight states and exceeds six. To assess the scale of these errors, PES reported with 90% confidence that New York State’s population exceeded anywhere from 400,000 to more than 1 million, or 1.89 to 4.99% of the population. Considering the counting cases, such a low margin of error should be considered impressive, but such a discrepancy could have major consequences as the last seat in the US House of Representatives, since 1940, decided by at least 89 people and not more than 17,000 yen. Most of the original comment PES results focused on the consequences of race errors, showing that many states that were overcounted were blue, while many that were undercounted were red. The errors, which seemed to favor one party over another, were even labeled “a scandal” and the census cleared as “A bust.”

These are overreactions, and the question remains: What should we do about these small, but statistically and politically, flaws?

This is a conundrum that our nation’s leaders have struggled with since the founding of the country. During the last century, two distinct approaches have dominated. One depends on focusing money and energy on mobilizing more census takers and on other system reforms to reduce errors. The other involved statisticians, who worked to develop techniques that could accurately measure error and then make corrections to census numbers. Both approaches are still important, but the scale of 2020 miscounts suggests that an older method of dealing with census errors needs to be reinstated: We should expand the House and Electoral College, so that some or none of the states lose representation. of an uncertain quantity. We should try to count better and correct as many errors as we can, but our democracy will be stronger if we also lower the stakes of each census. The representation is not necessarily a zero-sum game.

The earliest known The reference to a census low comes from Thomas Jefferson, then secretary of state, who wrote in 1791 about the previous year’s census, the nation’s first census. Jefferson wrote to his reporters in Europe, assuring them that the American population was several percentage points larger than officially claimed. It’s hard to say if this is really the case, but the story makes it clear that concerns about omissions and shortages began more than two centuries ago. In the decades that followed, disasters and mismanagement caused serious omissions, such as when the official in charge of counting Alabama’s residents died before his work could be completed. above Census of 1820or when many California records (including the entire San Francisco County) are burned after Census of 1850.