Wildfires in the Northwest are usually grass fires. Climate change is not a significant factor.

When many people think of wildfires in the Northwest, they picture a burning forest.

But in reality, most wildfires in the Northwest are grass or grassland fires, with trees playing only a minor role.

As we will see, grass fires have little to do with climate change, but a LOT to do with flammable invasive grasses spread by humans and ignited by humans. And such grass fires can then contribute to wildfires in neighboring forests.

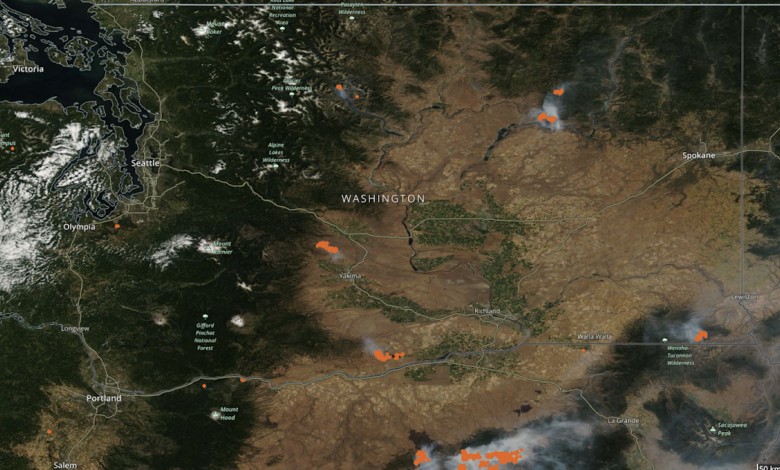

Take a look at this satellite image from earlier this afternoon (from NASA’s MODIS satellite). You can clearly see smoke from some of the fires in eastern Washington and Oregon. The satellite can also sense heat from the fires (orange dots).

If you look closely, you will see that very few fires occur in high elevation forested areas. Most involve large grasses and vegetation (including small shrubs).

For reference, here is information on current fires from the Northwest Fire Coordination Center.

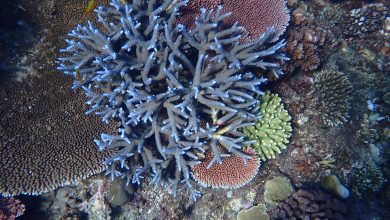

One of the most active fires in Washington is the Black Canyon Fire northwest of Yakima, which has burned over 4,500 acres of grassland (see photo below).

The largest fire in the region is the Lone Rock Fire in northeastern Oregon, which has now burned over 131,000 acres. Grass and brush. Most of the fires in our region…and most of the smoke…are from grass and grassland vegetation.

In fact, the USDA Fuelcast website diagnoses available grass fuel/range (see latest determination below). Abundant, above-average values are in eastern Oregon and Washington (dark green) thanks to a wet spring and dead grass left over from last year.

It is important to note that the high hazard levels of light fuels like grass are NOT due to drought but to above normal rainfall during growth period.

High summer temperatures and drought have little effect on grass fire risk because our dry summers can almost always dry out and cure grasses and similar weeds.

Consider the Columbia NWR RAWS site near Othello (nearby terrain image shown).

The ten-hour fuel moisture percentages (light vegetation moisture levels) for this location over the past several months are shown below. Below about 12% is dry enough to burn. Obviously, such fuels have been dry enough to burn for months. Every summer, such fuels are ready to burn. With or without global warming.

But something HAS changed that makes grazing/grass fires more likely: the replacement of native (less flammable) brushgrasses with invasive, highly flammable grasses like cheatgrass (also known as grassoline).

Here is a map of where cheatgrass has moved in. Large areas in our area.

Additionally, these human-dispersed flammable grasses are more likely to catch fire today, due to population growth as well as human fire-starting activities (from fireworks and off-road vehicles to shooting range practice to poor electrical infrastructure, to name just a few examples.)

Strong winds play a major role in the spread of grass fires, which is especially noticeable on the low, windy eastern slopes of the Cascades.

Too much of the media blames grass and grassland fires on climate change without any factual basis or supporting information. Grass/grass fires also play a large role in causing wildfires, which I will discuss in a future blog post.