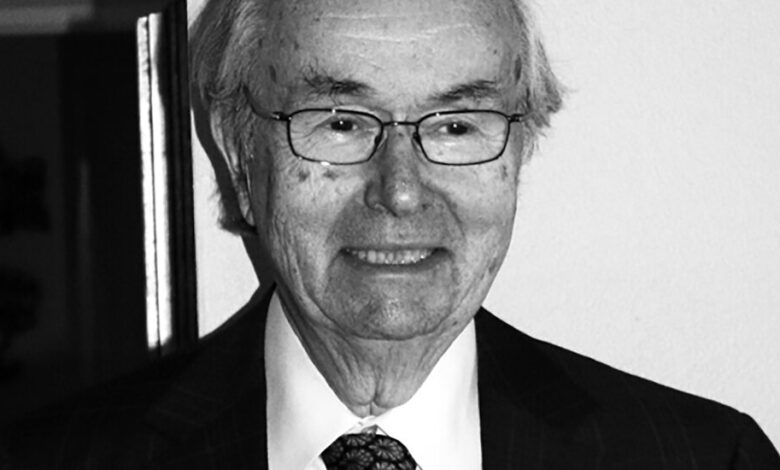

Frank Gilbert, New York and Beyond Conservator, Dies at 91

Frank Gilbert, a conservationist who helped save Grand Central Terminal from destruction by a 55-story skyscraper and in the mid-1960s incubated New York City’s pioneering landmark law, which promotes conservation movements across the country, died May 14 in Chevy Chase, he was 91 years old.

The cause was pneumonia and complications of Parkinson’s disease, his wife, Ann Hersh Gilbert, said.

Mr. Gilbert, an attorney who served as a New York City legislative lobbyist in Albany, was instrumental in drafting the belated closure of the city’s granaries following the demolition of downtown Pennsylvania Station. Beaux-Arts railroad designed by McKim in 1963, Mead & White on the west side of Manhattan.

The Act, passed by the City Council and signed in 1965 by Mayor Robert F. Wagner, states that the city’s global status “cannot be maintained or enhanced by disregarding historic heritage. and architecture of the city and by resisting the destruction of such cultural properties. ”

The Law of Creation Mold Conservation Committee and empower it to designate buildings that are at least 30 years old and of historical or architectural value and to prevent them from developing or demolishing.

Mr. Gilbert served as first secretary of the newly minted committee from 1965 to 1972 and then chief executive officer until 1974. During that time, Grand Central’s fate was great for him.

“I was worried because the Chairman of the Milestones Committee told me – what happened to Penn Station must not happen to Grand Central,” Mr. Gilbert recalled in an interview with New York Conservation Archives Project In 2011.

“I guess from the very beginning, my job was really to make sure we followed the right process and didn’t let the banana peel off,” he added. “I realized how serious the situation was. My main thought is to really be very careful, and prepare for a very difficult situation. ”

The failed Penn Central Railroad had hoped to build a skyscraper above the Grand Central Station it owned, and use the office rents to cover the company’s shortfall due to train travel. decline.

But the committee declared the station a landmark in 1967 and decided that all of Penn Central’s proposed designs for the skyscraper would overshadow the station’s architectural differences. .

Penn Central sued. Nine years later, a State Supreme Court judge overturned the place designation, ruling that preventing the bankrupt railroad from earning the income it would receive from the office tower would caused “economic hardship” and thus led to the unconstitutional expropriation of its assets.

Mr. Gilbert and other guardians of Grand Central rally support from a range of conservationists, including famous architects and bold names like Jacqueline Onassis, to maintain the landmark designation as the city pursues appeals to the courts. Higher level.

In 1978, the US Supreme Court affirm the city government to preserve a landmark. The court found that the designation of the place did not preclude the use of Grand Central as a railway station and that the company could not claim that the construction of the office building was necessary to maintain the profitability of the site. . The railway has admitted that it can profit from the station “in its current state”.

The Supreme Court’s 6-3 majority decision cited a summary of the amicus drafted by Mr. Gilbert, who was then assistant general counsel with the National Foundation for Historic Preservation in Washington. His summary indicates that many cities around the country, including New Orleans, Boston and San Antonio, have approved landmark conservation laws modeled on New York statutes.

Paul Edmondson, president and chief executive officer of the National Trust, described Mr Gilbert as “a giant in conservatorship law”.

“In addition to his pivotal role in developing and defending New York City’s landmark conservation laws,” Edmondson said in a statement, “he is responsible for safeguarding thousands of historic properties. and neighborhoods around the country through its work in helping communities develop counties. ”

Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, an early appointee to New York’s landmark commission and its longest-serving member, said of Mr. Gilbert in an email: “Always wanted to do the right thing, he did it. Working to balance the complex needs of all parties – property owners, the public, the press, developers and conservationists. ”

Frank Brandeis Gilbert was born on December 3, 1930, in Manhattan to Jacob Gilbert and Susan Brandeis Gilbert, both attorneys. His mother was the daughter of Louis D. Brandeis, a judge of the United States Supreme Court.

After graduating from Horace Mann School in the Bronx, Gilbert earned a bachelor’s degree in government from Harvard College in 1952, served in the Army from 1953 to 1955, and graduated from Harvard Law School in 1957.

From 1973 to 1993, he was chairman of the graduate committee of the Harvard Crimson, the student newspaper. Earlier this month, he was one of the Crimson alumni signed a letter condemns editorials supporting the “Boycott, Reject, Punishment” movement against Israel in the name of what it calls a free Palestine.

“The BDS movement claims to seek ‘justice for the Palestinians’ – a goal we share – but in reality it seeks to eliminate Israel,” the letter read.

In 1957, Mr. Gilbert joined the legal department of the Public Housing Authority in Washington and joined the New York City planning department two years later. He married Ann Hersh in 1973.

From 1975 to 1984, Mr. Gilbert was principal site and conservation law advisor to the National Trust for Historic Preservation and was its senior representative until 2010.

He has advised local and state governments on conservation laws and matters related to the designation of specific landmarks and establishment of historic districtslike the ones New York City has created in SoHo, Brooklyn Heights, Greenwich Village and Chelsea.

Mr. Gilbert remember in the Archives Project interview that when the fledgling committee officially selected its first landmark batch, The Herald Tribune’s headline declared “Twenty Buildings Saved!”

“My response at the time,” he said, “was that “20 buildings are designated” and we have a lot of work to do on these 20 buildings before they can be saved.”

He is shown to have foreseen the decades-long legal battle that followed against Grand Central and its disputes with the real estate industry and with individual developers over the commission’s expansion of powers in designation as a landmark for the interior of the buildings as well as the entire surrounding area.

On its 50th anniversary in 2015, the commission designated 1,348 individual landmarks, 117 interiors, and 33,411 properties in 21 historic districts.