Can carbon monoxide foam help with inflammation?

The foam incorporates a small amount of gas that can be delivered to the gastrointestinal tract to fight colitis and other diseases.

Carbon monoxide best known as a potentially lethal gas. However, in small doses, it also has beneficial qualities: It has been shown to reduce inflammation and may help stimulate tissue regeneration.

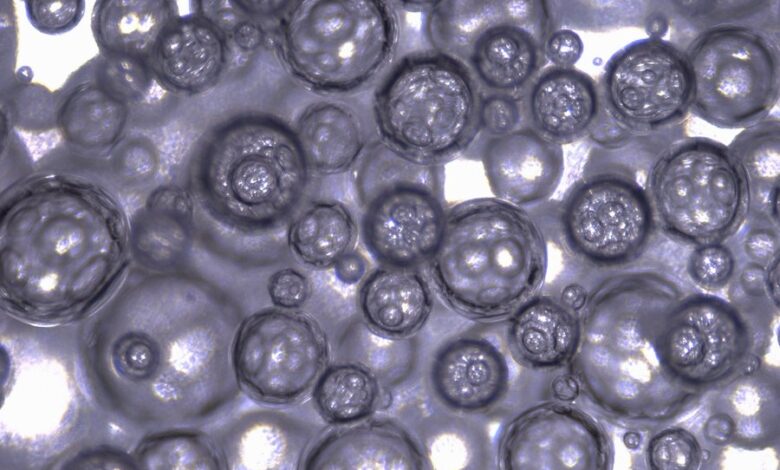

Note: Researchers at MIT and several other institutions have designed this foam that can deliver carbon monoxide bubbles to the digestive tract and other body organs. Image credit: Traverso Lab/MIT

A team of researchers led by MIT, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, University of Iowa, and Beth Israel Principal Medical Center has now devised a new method to deliver carbon monoxide into the body while eliminate its potentially dangerous effects. Inspired by the techniques used in molecular cuisinethey can combine carbon monoxide into stable foam that can be delivered to the gastrointestinal tract.

In research In mice, researchers have shown that these foams reduce colon inflammation and help reverse acute liver failure caused by acetaminophen overdose. New technique, described in Medical translation science The paper, the researchers say, could also be used to deliver other therapeutic gases.

“The ability to deliver gas opens up entirely new opportunities for how we think about therapeutics. We don’t usually think of gas as a treatment that you would take by mouth (or possibly be administered rectally), so this offers an exciting new way to think about how we can help patients,” said Giovanni Traverso, Karl van. Tassel Assistant Career Development Professor of Mechanical Engineering at MIT and a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Traverso and Leo Otterbein, professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, are the lead authors of the paper. The lead authors are James Byrne, a physician-scientist and radiation oncologist at the University of Iowa (formerly a resident of the Mass General Brigham/Dana Farber Radiation Oncology Program), and a genus research arm at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research; David Gallo, a researcher at Beth Israel Deaconess; and Hannah Boyce, a research engineer at Brigham and Women’s.

Foam delivery

Since the late 1990s, Otterbein has studied the therapeutic effects of low doses of carbon monoxide. Gas has been shown to prevent rejection of transplanted organs, reduce tumor growth, and correct inflammation and acute tissue damage.

When inhaled at high concentrations, carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin in the blood and prevents the body from getting enough oxygen, which can lead to serious health effects and even death. However, at lower doses, it has beneficial effects such as reducing inflammation and promoting tissue regeneration, Otterbein says.

“We have known for many years that carbon monoxide can have beneficial effects in all sorts of diseases when used as an inhaled gas,” he said. “However, it has been a challenge to use it in the clinic, for a number of reasons related to safe and reproducible management, and the concern of medical personnel, which has led to to the fact that people want to find other ways to use it.”

A few years ago, Traverso and Otterbein were introduced by Christoph Steiger, a former MIT postdoc and author of the new study. Traverso’s laboratory specializes in the development of new methods of delivering drugs to the gastrointestinal tract. To solve the gas distribution challenge, they came up with the idea of incorporating the gas into the foam, in the same way that chefs use carbon dioxide to foam fruit, vegetables or other flavors.

Culinary foam is typically created by adding a thickener or gelling agent to a pureed liquid or solid, then whipping it to combine with air, or using a specialized siphon to inject the gases. as carbon dioxide or compressed air.

The MIT team created a modified siphon that can be attached to any type of gas-filled tube, allowing them to incorporate carbon monoxide into their foam. To create the foam, they used food additives such as alginate, methylcellulose and maltodextrin. Xantham gum is also added to stabilize the foam. By varying the amount of xantham gum, the researchers were able to control the time it took for the gas to escape after using the foam.

After demonstrating that they could control the timing of gas release in the body, the researchers decided to test the foam for a number of different applications. First, they studied two topical applications, similar to creams, to soothe itchy or inflamed areas. In a study in mice, they found that the foam rectal delivery reduced inflammation caused by colitis or radiation-induced prostatitis (proctitis that can be caused by radiation therapy for cervical cancer or prostate cancer). Prostate).

Current treatments for colitis and other inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease often involve drugs that suppress the immune system, which can make patients more susceptible to infections. Treating those conditions with foams that can be applied directly to inflamed tissue offers a potential alternative or complement to those immunosuppressive treatments, the researchers say. While the foams were delivered rectally in this study, they can also be delivered orally, the researchers say.

“These foams are easy to use, which will help transition into patient care,” says Byrne.

Dose control

The researchers then began investigating possible systemic applications in which carbon monoxide could be delivered to distant organs, such as the liver, because of its ability to diffuse from the gastrointestinal tract. to other places in the body. For this study, they used a mouse model of acetaminophen overdose, which causes severe liver damage. They found that gas delivered to the lower gastrointestinal tract could reach the liver and significantly reduce the amount of inflammation and tissue damage there.

In these experiments, the researchers did not find any adverse effects after using carbon monoxide. Previous studies in humans have shown that small amounts of carbon monoxide can be safely inhaled. A healthy person has a carbon monoxide level of about 1% in the blood, and studies in volunteers have shown that levels as high as 14% can be tolerated with no adverse effects.

“We think that with the foam used in this study, we haven’t even reached the level we were concerned about,” says Otterbein. “What we’ve learned from the inhalation trials opens up a way to say it’s safe, as long as you know and can control how much you’re taking, like any drug. That’s another nice aspect of this approach – we can control the exact dosage. “

In this study, the researchers also created gels containing carbon-monoxide, as well as gas-filled solids, using techniques similar to those used to produce Pop Rocks, hard candies containing pressurized carbon dioxide bubbles. They plan to test those in further studies, in addition to developing foams for possible trials in patients.

Written by

Source: Massachusetts Institute of Technology