Barbara Kruger: A Way With Words

Barbara Kruger changed the way the world saw the world – its visual language, including art, advertising and graphic design. She has been less successful in changing the way the world works, especially in regards to gender injustice – the overwhelming oppression of women, male domination (ditto) – and diseases. epidemics such as war, consumerism, and poverty.

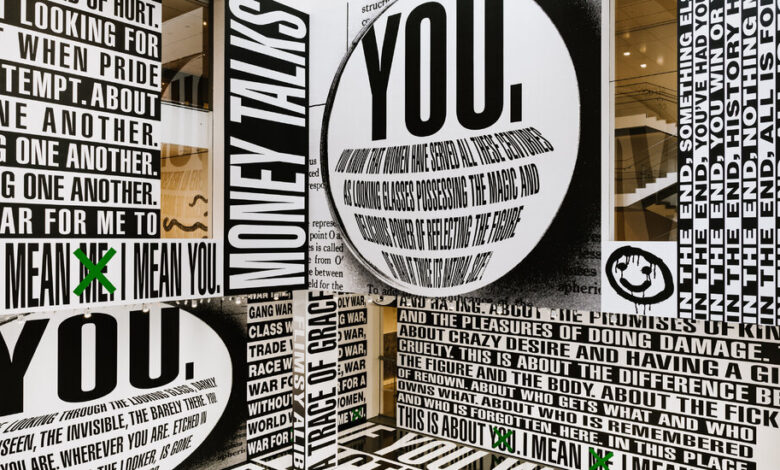

But that’s certainly not for lack of trying. Since the late 1980s, Kruger has combined her skills as an artist, feminist, writer and graphic designer into a number of memorable and resonant works of public art. best of her time. Right now, the intensity of her effort can be seen in two immersive screens in Manhattan: a large installation titled “Think About Friend. I mean I. I Mean You. “that envelops Museum of Modern Art’of the vast Marron Family Atrium – floors and walls – in language, and a group of individual pieces fill the spacious galleries on 19th Street of David Zwirner, who started representing the artist in 2019, in partnership with Sprüth Magers.

Kruger is known for her glamorous, red-framed montages that begin with slightly vintage black-and-white shots that give off a well-processed 1950s air. (They come from a large image bank—an archive that Kruger has assembled from magazines, newspapers, and illustrated books over the decades.) To these, she adds brief phrases. , almost koan-like, blunt observations and epochal imperatives. their economy and style – usually a few words in blocky white sans-serif font on one or more red bands or blocks.

These word-picture combinations range in size, from small posters surreptitiously plastered on urban walls in her early years, to mural-sized works and more recently digital screen. They tell dire truths about our society, our history, and our thoughts that Kruger rejects, rather, calls “the art of politics.” Her words tap into our inner lives and challenge our often naive assumptions about both our own mechanics and that of the world. As she describes, with the frequent lack of polish, in Interview: “My work has always been about power and control, bodies and money and that sort of thing.”

Many of Kruger’s phrases have made their way into the global consciousness, if they are not already famous from George Orwell, Tina Turner or – in the case of the blunt confession of “Untitled (I shop because I am me)” “- Descartes. The words appear on the screen, created by Kruger in 1987, in a red square powered by a large hand (unchanged).

The most famous is a statement of self-evident truth, metaphorically speaking: “Untitled (Your body is a battlefield).” This work began in 1989 as a poster commissioned by Planned Parenthood to publicize Women’s March in Washington, but it was rejected. Kruger just removed the parade information from the sticker file and it became a work of art, as well as a promotional poster. reproductive freedom. The five words that mark a woman’s face are divided in the middle into positive and negative images – that is, opposites. Its widespread use was facilitated by Kruger’s disinterest in copying his work.

Kruger came to art from outside the art world and art schools. Born in Newark in 1945, she attended Syracuse University and later attended Parsons School of Design, where she studied with Diane Arbus, a photographer of the marginalized, and Marvin Israel, an influential art director. Her first job out of college was a great one: working in graphic design at Condé Nast for about a decade. During this time, she gradually realized she wanted to be an artist. After a while trying to do the paintings she exhibits, she weaponized her graphic design skills.

In the late 1970s and early 80s, Kruger became one of a number of artists – mostly women – who rearranged and expanded upon Conceptual Art’s relatively modest coupling between visual and text, which she once called “a closed system”. These artists drew on popular culture and aimed at a larger audience. Sometimes, the text disappears into images, as in Cindy Sherman’s “Film Stills,” which consists of female film stereotypes that provide stories of their own. In other cases, starting with Kruger, images and text are combined and layered, creating an assortment of images and language that influences art as well as all areas of design.

Kruger has been criticized for its repetitive, mythical or propaganda imagery. None of these are correct. Her work can feel incessant at times but her voice, though pressuring, is too restrained and witty to speak or propagate. And Kruger’s ideas evolved, while her use of the language became more fluent. She is also proficient in the latest distribution systems, translating previous works through digitization, animation and sound.

And yet, as the installation at MoMA, organized by Peter Eleey and Lanka Tattersall, shows, Kruger continues to work with words alone, on a huge scale and in dizzying numbers. “Thinking Friend. I mean I. I Mean You. ” is a complete no-print, no-animated affair—also stripped of her visuals, as are most of her major installations.

Slender towers. It engulfs the three very high walls of the atrium and its floor with blocks and threads in black on white or white on black text in different sizes, with green accents for the crossed out pronoun. The latest work in both locations, it feels emotional, volatile and even ominous – like these times. Switching blocks of this type can rotate, cuboidally and vertically, if you move too fast.

Slow down and conflict objects confront you. They see themselves as unstable and vulnerable, touch on love and war, and flirt with the apocalypse. Things can start out almost abstract – like a word game – and get weird. A section that almost begins with a hymn – “Wartime, war crimes, war games” – and eventually develops into “War for a world without women”, which sounds chilling. . Another text begins with terrifying opposite emotions: “This is about love and longing. About shame and hate. “Towards the end, it is web-specific: “About the remembered and the forgotten. Here. Here.” The most sobering moment of the MoMA installation is happening underfoot, in the words of George Orwell: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping a person’s face, forever.” This sentence is easiest to read if you exit the Atrium, go up a level or two above and look down. It might feel safer there.

Kruger’s MoMA committee was originally intended to be accompanied by a survey organized by three museums: Art Institute of Chicagothe Los Angeles County Museum of Art and MoMA. The survey’s New York stop was at MoMA PS 1. But in the fall of 2020, PS 1 dropped out, citing scheduling conflicts caused by Covid-19. The survey reached the remaining two museums.

And right after that, Zwirner stepped in, taking as many works as he could from the survey – which turned out to be 17 recent or up-to-date entries, compared with 60 in Chicago and 35 in Los Angeles. The rooms in Zwirner are a bit more like MoMA 53rd Street, and have the advantage of being on the ground floor and free of charge.

At Zwirner, some of the static texts have been reprinted in larger volumes, such as the nagging untitled work from 1994, white on red, which begins “Our people are better than yours.” ,” and disappeared from there (“Smarter, stronger, more beautiful, and cleaner… “).

Some pieces turn previous efforts through LED lighting into near-new compositions, adding soundtracks, tiered jigsaw puzzles, and entertainment value. But the technology also allows Kruger to expand his language and think out loud, which is actually more vivid. The phrase “Your body is a battlefield” is replaced by the absurd and violent “My coffee is a motorboat” “Your skin is cut.” One of the alternatives to “So I shop,” might be this call for radical political rallying: “So I hate.”

Arguably the best work at Zwirner is “Untitled (That’s How We Do It),” a work that installs vinyl wallpaper following Krugerstyle’s seepage-now, flood-tracing into the wider world, into ads, clothing brands (Hello, Supreme), political posters, sleazy online posts, and t-shirts. It offers an almost overwhelming look at culture on the go, whether seen as art or archives.

More recently, Kruger’s popularity has been heightened with the reversal of Roe v. Wade, attracted attention on her famous poster advocating for women’s reproductive rights. She won’t be afraid to stand out. As she told Carolina Miranda in the Los Angeles Times, when deciding dimly, “It would be nice if my work became classic.”

Barbara Kruger: Thinking about Friend. I mean I. I mean you.

Through January 2, 2023, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd St, Manhattan, (212) 708-9400; moma.org.

Barbara Kruger

Through August 12, David Zwirner Gallery, 519, 525 & 533 West 19 Street, Chelsea, (212) 727-2070; davidzwirner.com.