Are Atmospheric Rivers a New Meteorological Phenonomon?

For the past year or so, whenever there’s been a lot of rain on the West Coast, the media has made headlines with “atmospheric rivers.”

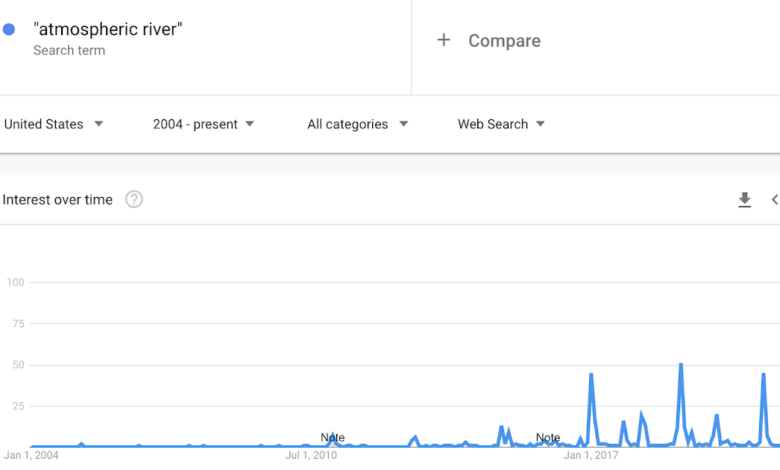

Ten years ago, hardly anyone talked about such rivers. Now, they are mentioned all the time!

To illustrate the change, here’s google trend analysis search for “atmospheric rivers” from 2004 to present. Before 2010, almost no one searched for this term. But this November, it’s very, very popular. The same is true of press and online mentions.

What has changed?

Several people have asked me if atmospheric rivers are a new weather feature caused by forced global warming.

Others asked me if global warming would make atmospheric rivers stronger and more frequent.

Well, it’s time to “clean up the air.”

The phenomenon known today as atmospheric rivers are like hills. They do NOT become stronger or more frequent on the US West Coast, although they may occur in the future.

I should note that this topic is one I have published in peer-reviewed and Federally-supported (NSF) literature for research.

Atmospheric River 101

Atmospheric rivers are streams of moisture (water vapor) that move into the mesosphere from the tropics or subtropics. They are best observed via vertical water vapor sensitive weather satellite imagery.

In the example below, the total amount of water vapor in a column is presented for a single time, with red and purple indicating the highest values, commonly found in tropical regions. This makes sense because warm air can “hold” more water vapor than cooler air. But look closely and you’ll see bands of steam stretching into the middle.

These are atmospheric rivers and some are clearly visible at this point – this is NOT unusual.

The term “atmospheric river” was first used in paper by Zhu and Newell in 1994, titled “Atmospheric Rivers and Bombs.” Bomb is a term used to refer to rapidly developing cyclones at mid-latitudes.

They note that rapidly growing low-pressure centers often have a moisture filament associated with them. They call these filaments “atmospheric rivers” because they move large amounts of water vapor, comparable to large rivers like the Mississippi and the Amazon.

The term “atmospheric river” was evocative and intriguing, and the name quickly entered meteorology and was subsequently picked up by the media.

The phenomenon of strong winds with high humidity was well known before 1994, but the names used, such as “low-level warm area jet” did not become the buzzword. . Wonder why.

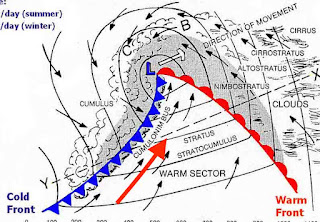

To illustrate some previous uses of the idea under a different name, below is an old USFS image showing a vortex in the center and front sides: I added a red arrow to highlight the area of strong and humid currents in the southwest described in the literature.

Global satellite imagery of humidity, available in the 1990s, provides dramatic graphics of the phenomenon and helps to make the feature public.

But there is something else. The advent of high-resolution numerical weather prediction has provided very graphic images of what happens when atmospheric rivers hit West Coast terrain: large amounts of water vapor can be turns to rain when strong winds and abundant moisture in atmospheric rivers are forced to rise coastal mountains.

To illustrate here is an example from December 2010. A long stream of moist air (atmospheric river) has moved from western Hawaii to the Washington coast.

And the simulated 24-hour rainfall is huge: 5-10 inches in the mountains. Some atmospheric rivers have fallen twice that level.

Atmospheric rivers provide substantial rainfall for the entire West Coast, from northern Mexico to southeastern Alaska, with the proportion of annual precipitation associated with rivers increasing southward.

There is an extensive literature and substantial observational evidence showing that over the past century there has been NO overall upward trend in atmospheric river intensity and frequency over the West Coat..

Climate simulations show a modest (10-20%) increase in atmospheric rivers by the end of this century if greenhouse gases continue to rise. That increase, coupled with less snow and ice, could contribute to increased flooding, especially after 2050.