4 of 2021’s biggest archaeological finds – including a ‘game changer’: NPR

The pandemic has made the future uncertain, but archaeologists are still working to uncover our past.

AFP Contributor / AFP via Getty Images

hide captions

switch captions

AFP Contributor / AFP via Getty Images

The pandemic has made the future uncertain, but archaeologists are still working to uncover our past.

AFP Contributor / AFP via Getty Images

Global shutdowns and political strife make this a difficult year for archaeologists, at least in terms of getting out there on excavation sites.

But despite what many might think, archeology is more than just sifting through the land for lost artifacts.

A lot of the work actually takes place far away from the excavation site, in the laboratory where scientists are analyzing these found objects, trying to piece together the unrecorded history of mankind.

So while archaeologists spend less time digging, 2021 is still a favorable year in archeology.

We take a look at some of the biggest advances in archeology from this year. We talked to Putty grinding machine, a team of four female archaeologists from different disciplines dedicated to highlighting the historical and indispensable mark of women in the “science of digging”.

They tell us what they think are some of the most important developments in their field in 2021.

Neanderthals may be more human than we thought

Dr. Rebecca Wragg Sykes is an archaeologist who studies Neanderthals, a relative of modern humans that went extinct about 40,000 years ago.

She chose to highlight a paper published last April in the magazine Scientific reports about the discovery of 100,000-year-old Neanderthal footprints on a coastal area of the Iberian peninsula, Spain.

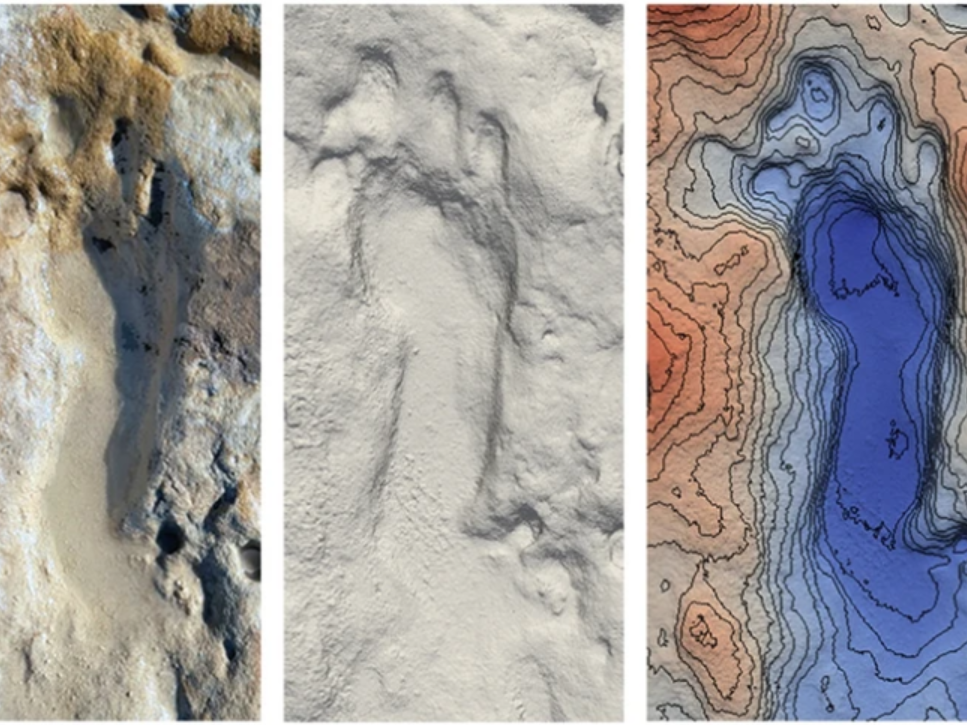

The researchers used state-of-the-art imaging technology to collect data and analyze 100,000-year-old footprints.

Eduardo Mayoral et al / Scientific report

hide captions

switch captions

Eduardo Mayoral et al / Scientific report

The researchers used state-of-the-art imaging technology to collect data and analyze 100,000-year-old footprints.

Eduardo Mayoral et al / Scientific report

Although these are not the first Neanderthal footprints discovered, they are very special.

“This is especially cool, because it’s a mixed-age group, including children, some quite young,” says Wragg Sykes.

Age diversity is key here and really helps to challenge a common assumption that Neanderthals forage in solitude, with adults breaking away from groups to forage for children.

Instead, the discovery offers support for the theory that hunting and gathering may have been a single family affair, involving a collaborative and intergenerational effort.

Notably, the paper also notes that some of the children’s footprints were “grouped in a chaotic arrangement,” as if they were playing.

“It’s a corner of Neanderthal life that we don’t get to see very often,” said Wragg Sykes, adding that the discovery helps bring a sense of humanity to the not-so-distant human relative.

The powerful women of ancient Spain

A 3,700-year-old female skeleton decorated with precious objects has been found in La Almoloya’s tomb and shows the power of women in society.

Research group Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrânia / Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona

hide captions

switch captions

Research group Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrânia / Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona

A 3,700-year-old female skeleton decorated with precious objects has been found in La Almoloya’s tomb and shows the power of women in society.

Research group Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrânia / Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona

Dr. Brenna Hasset is a biological archaeologist who describes her specialty as fascinating and exciting, as well as a bit creepy.

“My job is basically digging up the dead. So I research the lives of people in the past, to try and understand how they lived, how they died.”

This year, Hasset is most delighted by a paper published in a magazine Ancient about a 3,700-year-old grave site found in Spain. A grave at the site contains the remains of a man and a woman, along with some personal belongings.

Excavators found the woman’s remains decorated with a number of precious objects, such as bracelets, necklaces, and a silver crown or tiara.

Hasset says you can tell how much someone means to their community by the things they bury.

Research group Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrânia / Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona

hide captions

switch captions

Research group Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrânia / Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona

Hasset says you can tell how much someone means to their community by the things they bury.

Research group Arqueoecologia Social Mediterrânia / Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona

Hasset notes that a lot can be learned about someone’s role in society by what they bury. The presence of such precious objects suggests that a woman holds a high social status and possibly even political power.

“We have always thought that these societies were run by masculine men and their important subjects to exercise power,” says Hasset. “When we see women with these particular artifacts, are we really seeing signs of some sort of female power?”

A million year old mammoth

DNA from mammoth teeth found preserved in the Siberian permafrost is more than 1,000,000 years old and is the oldest DNA ever sequenced.

Image of Koichi Kamoshida / Getty

hide captions

switch captions

Image of Koichi Kamoshida / Getty

DNA from mammoth teeth found preserved in the Siberian permafrost is more than 1,000,000 years old and is the oldest DNA ever sequenced.

Image of Koichi Kamoshida / Getty

Dr. Victoria Herridge is not exactly an archaeologist, she is actually a paleontologist specializing in ancient elephants.

She chose to highlight a paper published year nature last February reported successful sequencing of DNA taken from mammoth teeth found in the Siberian permafrost. The DNA is over a million years old and is the oldest DNA ever successfully sequenced. The discovery challenges the hypothesis that there was only one species of mammoth in Siberia at the time, instead expressing multiple gene lines. Researchers spoke to NPR’s All things Considered last February.

For Herridge, however, it’s the age of DNA that excites her the most, with broad implications for paleontology, archaeology and several neighboring fields, she said.

“For me, it’s like a proper game-changer!”

This DNA is particularly valuable, says Herridge, because the past millions of years have been a critical period for understanding mammalian evolution.

She points out that although the frigid conditions of the permafrost helped preserve DNA, the absolute age of the samples was nonetheless groundbreaking.

“It shows that you can get genetic information in a way, way, further away in time than we previously thought possible.”

Herridge made sure to highlight one of the paper’s co-authors, Patrícia Pečnerová, whose skillful laboratory techniques have made DNA sequencing possible.

“I think it shows that things that might have been considered impossible before may not be impossible. And so maybe we shouldn’t rule out the opportunity with careful lab work, careful and developed techniques.”

How not to lose track of us

Dr. Suzanne Pilaar Birch is an associate professor of archeology and geography at the University of Georgia in Athens.

She chose to feature a recently published article in nature on a new analysis of footprints discovered in the 1970s in Tanzania. The researchers returned to the site and, upon re-examination, determined that the tracks belonged to an early hominin species, not a bear-like animal, as was previously thought.

The prints are estimated to be about 3.6 million years old, making them the oldest evidence of bipedal locomotion of human ancestors. Nell Greenfieldboyce of NPR mention these findings earlier this month.

However, Pilaar Birch emphasizes this story not because of its extraordinary finds, but because it highlights the need to better preserve our archaeological assets.

“This is work that was done 50 years ago,” says Pilaar Birch, “[But] the workpieces generated from this rail were actually lost. “

She notes that if the embryos had been properly cared for, there might not have been a need to return to the field and we could have reached this important conclusion sooner.

Pilaar Birch says there is a need to improve the long-term preservation of archaeological assets and record management.

While many organizations struggle with funding, she says there’s been a movement to change that, especially in the areas of data storage and aggregation.

“It’s certainly an area where we’re seeing a lot of progress, and the National Science Foundation is very supportive and funding new database initiatives.”